Justices to Take Up Curbs on Prisoner Marriages, Correspondence

- Share via

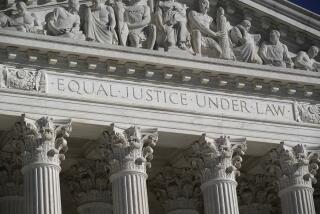

WASHINGTON — The Supreme Court, entering a sharp conflict between prison security and prisoner privacy, agreed Tuesday to decide how much authority states have to prevent inmates from marrying and from corresponding among themselves.

At issue is a federal appeals court decision saying that prisoners retain a “fundamental human right” to marry--even when they cannot cohabit with spouses--along with a basic free-speech right to exchange letters.

Missouri Rules Voided

The appellate court declared unconstitutional Missouri prison regulations that required inmates to provide a “compelling” reason for marriage to another prisoner or an outsider and that prohibited correspondence between prisoners in different institutions without special permission.

Unless they can show that such activities are “inherently dangerous,” state officials must adopt less restrictive means of maintaining prison security and discipline, the appeals court said.

The case, to be heard in the term beginning in October, presents the justices with an opportunity to resolve a growing array of conflicting decisions by lower courts on the privacy rights of prisoners.

The dispute arose in 1984, when Missouri inmates filed a class-action suit challenging the validity of the restrictions, mainly as they were applied to a state correctional center containing facilities for both male and female inmates.

A federal District Court found the rules unconstitutional, and later the U.S. 8th Circuit Court of Appeals in St. Louis agreed.

2 ‘Compelling’ Reasons

The appellate court said that, although the state might justifiably regulate the time and manner of inmate marriages, it had gone too far in setting rules that virtually barred marriage. Only pregnancy or the birth of an illegitimate child was considered a “compelling” reason for marriage.

The court said also that, instead of virtually banning prisoner correspondence, the state should have opened mail between inmates to ensure that there was no threat to security.

In their appeal to the justices (Turner vs. Safley, 85-1384), Missouri officials argued that, although inmates retain some constitutional rights, they do not enjoy the same liberties as free citizens.

California Case

In other action, the justices:

--Refused, over three dissenting votes, to review a decision last year by the California Supreme Court holding that a 1983 state law increasing the punishment for prison misconduct may be applied to inmates incarcerated before that law went into effect.

The state court, in a 5-2 decision (Ramirez vs. California, 85-1321), upheld the forfeiture of 95 days in sentence reduction credits imposed on Rudy J. Ramirez, pointing out that, although Ramirez had been imprisoned before 1983, his misconduct occurred after the new law became effective. Under the law that had been in effect when Ramirez was convicted and sentenced to prison, he would have forfeited only 15 days.

The high court majority, in a brief order, refused to review Ramirez’s appeal. Justice Byron R. White, joined by Justices William J. Brennan Jr. and Lewis F. Powell Jr., said that the court should have agreed to hear the case to see whether there was a violation of the constitutional prohibition against ex post facto laws. Four votes are required for review.

--Let stand the dismissal of a libel suit brought by a former air controller over an article on air safety published by The Washingtonian magazine. A federal appeals court held that, as an “involuntary public figure,” the controller must bear the heavy burden of showing that it was a defamatory article published with “actual malice”--that is, with knowledge that it was false or with reckless disregard for the truth. By contrast, private figures face the lesser burden of proving only negligence.

The suit had been brought by Merle W. Dameron, the only air controller on duty at Dulles International Airport in 1974 when an airliner crashed on approach, killing 92 persons. The article did not name Dameron but said “controller errors” had been assigned “partial blame” in some accidents, including the 1974 crash. Dameron charged that the story made him identifiable and was false (Dameron vs. Washingtonian, 85-1569).

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.