Studies Indicate Treatment Can Halt Growth of HTLV-III Organism : Experimental Drug Plays Trick on Deadly AIDS Virus

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Azidothymidine, one of about six promising new drugs being tested nationwide in the battle against AIDS, begins with fish sperm and ends with what amounts to a chemical trick played on the virus responsible for one of history’s most vicious and baffling medical mysteries.

Based on early studies of the drug, scientists believe that AZT can stop the growth of HTLV-III--the virus that causes AIDS--by disrupting the chemical chain needed by the virus to replicate itself inside the body of an AIDS patient.

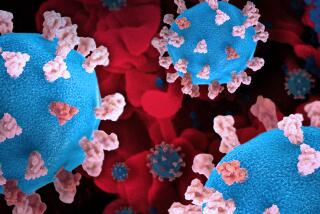

Viruses are special life forms with the ability to invade cells and control the way they behave. HTLV-III, which causes AIDS, is also a special kind of virus called a retrovirus--one of only four known human retroviruses.

Sinister Viruses

Human retroviruses are an especially sinister class of viruses whose genetic material consists of RNA (ribonucleic acid), rather than the DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) found in every other organism. When retroviruses enter a cell, they use an enzyme known as reverse transcriptase to copy their RNA into DNA, which is then integrated into the DNA of the cell. In other words, the genetic material of the retrovirus becomes a permanent part of the host cell. Using the host cells as tiny “virus factories,” the AIDS virus then begins to multiply.

(By contrast, the virus responsible for the common cold--for example--is not a retrovirus. When it enters the respiratory cells of a person, it inflicts temporary discomfort but eventually leaves without becoming a part of the genetic makeup of the cells.)

Eventually, the HTLV-III retrovirus kills the critical T-4 helper cells in the blood, part of the body’s disease-fighting system involved in mobilizing antibodies to ward off foreign invaders. As T-4 cells begin to die, the body is left defenseless against infections that it could otherwise fight off.

One of the normal components of DNA is thymidine, which is used both by the host cell and by the virus to make DNA building blocks necessary for replication. AZT is a derivative of thymidine, similar to the natural substance but with a crucial difference: It allows the virus to begin replication, but prevents it from completing the process. As a result, multiplication of the virus is halted.

Breaks the Chain

This is how AZT works:

The host cell can tell the difference between the drug and the real thing, but the virus apparently cannot. “When the virus picks up AZT and tries to put it into the chain, it breaks the chain and the virus can’t grow,” said Dr. Robert T. Schooley, director of the experimental AZT program at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston. “It is much more toxic to the virus than it is to the host.”

Dr. Samuel Broder of the National Cancer Institute, who performed the first studies of AZT, explained it this way: “One end of the molecule of the newly growing DNA strand is perfectly normal, so it is accepted. But another end of the molecule has been modified chemically (by the drug). Think of a male and female adapter. One adapter has a male end, but the female end is cemented over. At that point, it is no longer possible for the chain to go on.”

Halting Growth Not Enough

It is not enough simply to halt the growth of the virus; to survive, a victim must somehow regain a functioning immune system. Schooley says early work with AZT has indicated the possibility that “the immune response can reconstitute itself all by itself”--meaning that additional treatment to enhance the damaged immune system might not be necessary.

Azidothymidine, also known as Compound S, was developed by Burroughs Wellcome Co. It was originally obtained from the sperm of fish, mostly herring and salmon, although methods have now been developed to produce it synthetically. The company is supplying the drug and paying the cost for each patient, estimated at $6,000.

Researchers are also enthusiastic about AZT because it does not seem to be toxic and because it is absorbed when taken orally, meaning that it does not have to be administered intravenously.

But most important, AZT appears to be one of the few drugs capable of crossing the “blood-brain barrier”--a complex body mechanism involving the blood vessels and brain lining that prevents most toxic substances from reaching the brain. This barrier prevents most beneficial substances from getting there too. Since the AIDS virus has been found in the brain--and has resulted in severe neurological problems for many AIDS sufferers--it also must be attacked there.

The program at Massachusetts General Hospital is one of several involving AZT now under way around the country. It recently was awarded $8.4 million in government funds over the next five years as part of an expanded federal effort to fight AIDS.

This is a “Phase II” study. In Phase I, the drug is first examined in the laboratory and in test animals, and later studied in a small number of patients to determine if it is toxic. Phase I testing has indicated that AZT causes few side effects.

Phases II, III

Phase II involves administering the drug to humans to see if it can arrest the disease. Phase III--a more extensive series of tests on humans--is the last experimental stage before the drug is made available to the public, and is much farther down the road.

“This is a drug that looks good in the laboratory,” Schooley said. “There are no bad side effects that we’ve found. We don’t think it will make them (patients) sicker. The major thing is the drug could have a big impact on their time. We would love to have it be a home run. But we’re also realists. We recognize that every step of the way you can encounter things you don’t expect.”