Potent Cancer Treatment Awaiting Test OK by FDA

- Share via

A new, experimental treatment has been developed for advanced cancer patients that, in laboratory mice, “appears to be 50 to 100 times more potent” than a related immune system therapy now being tested in humans, National Cancer Institute researchers announced today.

The first human tests of the novel immune system therapy, already approved by the cancer institute, await a final go-ahead from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

“This is certainly the most potent immunotherapy I have ever seen,” said Dr. Steven A. Rosenberg, chief of surgery at NCI. “I am by no means sure that this will work in humans, but I am quite excited that it might.”

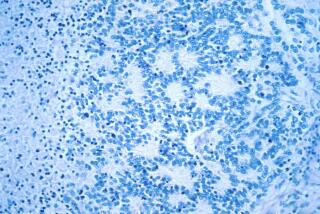

The therapy greatly stimulates white blood cells--called tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes--that naturally invade growing tumors to eliminate cancer deposits, including large liver and lung tumors in mice that had resisted previous experimental treatments, he said.

Rosenberg, who led the team of surgeons that successfully removed a cancerous growth from President Reagan’s colon last year, described the technique in the Sept. 19 issue of Science, released today.

Rosenberg, the study’s principal investigator, said the new approach is “the next scientific development” in the rapidly expanding field of immune system therapies for cancer. It is based on the theory that white blood cells normally found in growing tumors are capable of killing these tumor cells.

Rosenberg received widespread publicity last December when he reported in the New England Journal of Medicine promising initial results in treating advanced human cancers with a similar technique using the protein interleukin-2, a natural immune-system booster, to transform circulating white blood cells into activated killer cells, called “LAK” cells.

After that announcement, about 2,600 cancer patients called the NCI seeking the treatment. Since then, six medical centers, including the City of Hope in Duarte, have begun trials of the LAK cells that will involve several hundred patients.

In December, Rosenberg was criticized by some skeptical colleagues for overstating his findings and underemphasizing toxic side-effects of the high doses of interleukin-2, including severe fluid retention. Also, one patient death was caused by the treatment.

Killer-Cell Method

Of 55 patients treated through May, 21 showed “objective” shrinkage of their cancers, particularly patients with kidney cancers, according to Rosenberg. He said five others had a “complete” regression.

In his latest paper, Rosenberg said the new approach seeks to overcome the drawbacks of the killer-cell method.

The paper describes how tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes can be separated from mouse tumors in the laboratory and subsequently grown to 100 times their initial numbers over 15 days.

When injected back into the bloodstream of the mouse from which they were isolated in combination with interleukin-2, these purified white blood cells were “50 to 100 times more potent” than an equal number of activated killer cells in treating microscopic lung tumors.

The researchers also used the therapy against “large” lung and liver tumors in mice that “did not respond” to treatment with activated killer cells.

Cured of Tumor

When combined with “low” doses of interleukin-2 and “high” doses of the anti-cancer drug cyclophosphamide, all of the 12 mice tested were considered cured of liver tumors and 50% of 10 mice treated in another experiment were cured of lung tumors.

The anti-cancer drug had some effect against the tumor, but Rosenberg said its major role was eliminating “suppressor factors” in the mouse that blocked the action of the transferred immune cells.

In recent months, the researchers have completed the preliminary laboratory work that is necessary before human trials can begin. They have isolated tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes from surgical specimens of a variety of human tumors, including the skin cancer melanoma and kidney cancer.

The researchers found that the human white blood cells could be grown outside the body for up to two months. And they have produced large quantities of these cells and showed that--in the laboratory--they could kill the tumor cells from which they were isolated. “Our early results (in patients) will determine how quickly we progress,” Rosenberg said in a telephone interview from his Bethesda, Md., office.

He cautioned that, at most, 10 to 20 patients with cancers that had failed to respond to all standard treatments, including radiation and chemotherapy, might receive the “highly experimental” treatment in the first year of human trials.