Credited With Major Archeological Find : Incas: UCLA Student May Have Opened a New Door

- Share via

A UCLA graduate student who carried a class project to extremes is being credited with an archeological discovery in Peru that could prove of major importance in understanding the perplexing history of the Incas.

Although an official announcement from the Peruvian government last week said Reynaldo Chohfi made the discovery while flying over the Andes, Chohfi said in an interview that he actually found the ruins last winter while on the Westwood campus studying 30-year-old aerial photographs of the region.

He recently returned from Peru, where he hacked his way through the jungle to confirm what he had already concluded had to be there, climaxing a feat of scholarship and adventure.

Chohfi, a native of Brazil who has been in this country for 10 years, is credited with discovering the remains of a large settlement a few miles from the most celebrated of all the Inca ruins, the village of Machu Picchu.

It was a personal triumph for the 31-year-old archeology student, but his hands still hurt from insect bites. And he will never forget the big, black snakes.

Chohfi was joined on the expedition by a friend, Octavio Fernandez, an archeologist with Peru’s National Cultural Institute.

The two men traveled by train up the narrow twisting gorge toward Machu Picchu last month, and when it reached the end of the line, they set out on foot. The jungle was so thick in some areas that they had to use machetes to hack through the dense vegetation, Chohfi said.

Insects tore at their flesh, leaving wounds that have not healed. At one point, Fernandez nearly put his hand on a “big black snake,” one of several deadly reptiles they encountered as they made their way through the thick brush, Chohfi recalled.

After climbing for several hours, the two men came into a flat area that Chohfi had identified from the photographs.

Even Chohfi admits that he was startled by what they found.

Massive, Ancient Wall

A massive, ancient wall stretched along one side of the plateau.

“I had never seen anything like it,” Chohfi recalled.

The wall, he said, measured more than seven feet thick and it was at least that high.

Chohfi and Fernandez took a few pictures and then hacked at the thick vegetation as they traced the wall. Chohfi said they were stunned when they realized that it was more than 1,000 feet long.

Near the great wall, they also found the top of the walls of a small structure, which has been nearly buried under soil and rich vegetation. Chohfi is convinced that the wall and the building are part of what was once a major settlement.

The discovery “could be quite significant,” John Hemming, director of London’s Royal Geographic Society and an expert on the Incas, said in a telephone interview. He added that the importance of the site will not be known until it can be excavated.

Fascination With Architecture

Several other experts agreed.

Chohfi, who is working toward a master’s degree in archeology while pursuing an advanced degree in architecture, said he has been studying Machu Picchu since 1978 because of his fascination with architectural structures that maximize renewable resources, such as solar energy.

Nestled amid towering peaks at an elevation of 8,000 feet, Machu Picchu, the holiest shrine of the Incas, has long mystified historians. Its buildings, constructed of carefully cut stones reflecting an advanced stage of craftsmanship, have been dated as far back as 650 A.D., Chohfi said.

Although there is general agreement that the site was abandoned by the Incas during the Spanish conquest in the 1500s, there has been considerable disagreement over the role Machu Picchu played in the Inca civilization, a debate that started with its discovery by Yale historian Hiram Bingham in 1911. Bingham initially said he had discovered the Lost City of the Incas, the central governing seat of the sprawling Inca empire.

Religious Center

That accolade has gone now to a large settlement found a decade ago near the city of Cuzco, but most authorities still believe Machu Picchu was the Incas’ religious center.

Chohfi said he decided to study Machu Picchu because the Incas’ religious beliefs undoubtedly carried over into their architecture.

“The sun was their primary god,” he said in an interview at UCLA, adding that they also apparently revered other aspects of nature.

“If they worshiped the natural environment,” he added, they probably designed their city to gain the maximum benefits from the sun.

Three years ago, he visited the site as part of an expedition led by Reiner Berger, chairman of the archeology program at UCLA, and he found that Machu Picchu lived up to his expectations.

“It was a natural greenhouse,” he said. “It is all oriented to the sun.”

One of the things that struck Chohfi while there was the isolation of Machu Picchu. Since it is perched on the edge of a rock cliff, it would not have been possible to grow all the crops necessary to support the people of the village, he said.

Had to Be Others

That, in turn, led him to conclude that there were probably other villages some distance away that supported Machu Picchu. Although numerous smaller sites have been discovered in the area immediately around Machu Picchu, Chohfi was convinced there had to be others.

“We looked around that mountain site,” said Berger, who is Chohfi’s adviser. “There were some localities that looked like they might have ruins.”

But the area around Machu Picchu is largely inaccessible and covered with dense vegetation, thus denying them a chance to check out their theory. However, Chohfi made up his mind to continue his work after returning to UCLA.

Last year he enrolled in a course on remote sensing, the burgeoning science of using photographs from the air or space to study objects on the ground. The course was taught by Norman Thrower, director of UCLA’s Center for 17th- and 18th-Century Studies.

Aerial Photographs

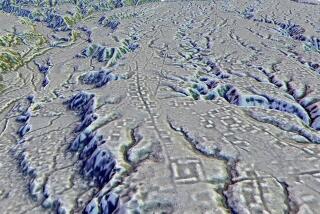

During the course, Chohfi acquired aerial photographs of the Machu Picchu region.

The photos, taken for a topographical study of the Peruvian Andes, showed a gentle slope on the opposite side of a deep gorge northeast of Machu Picchu. The photographs were taken from such a high altitude that details on the ground were hard to detect, but Chohfi was sure of one thing. Across one end of the slope was a straight line.

“The natural environment doesn’t have straight lines,” Chohfi said.

That left him convinced that the “line” was man made, and since no archeological ruins were known to exist there, he was convinced that he was on to something. A Southern California physician, Leo Kenneally, and his wife, Sharon, who are friends of Chohfi, agreed to underwrite a trip back to Machu Picchu so that Chohfi could verify his findings.

Hacked Through Jungle

So last month Chohfi flew back to Peru and was joined by Fernandez for the trip up the mountain.

After they hacked their way through the jungle, Chohfi found the straight line he had seen on the photographs. It was the massive wall.

Equally intriguing to Chohfi was the rich, dark soil of the area. Holding a small plastic bag of dirt that he brought back to study, Chohfi marveled at his own discovery.

“The agricultural productivity must be fantastic,” he said. “They had the water, the sun and the soil. What else do you need?”

He also found numerous grinding stones scattered throughout the area, further evidence that the new site was a major agricultural satellite for Machu Picchu.

He plans to do scientific dating of some small samples of pottery shards he found at the site, but he believes that the new discovery dates back to the same time frame as Machu Picchu.

Named Village

Chohfi and Fernandez named their village Maranpampa--”maran” means grinding stone and “pampa” means soil.

After hiking back down the trail, the two men reported their findings to Peru’s National Cultural Institute, and the Peruvian government immediately announced that a major archeological site had been discovered. That announcement included several errors, including a statement that the men had not actually reached the site on foot. But Chohfi has a series of photographs to prove that he was, indeed, there.

Although people in the immediate area undoubtedly had stumbled across the ruins, the site was not known to the scientific community, according to several experts.

“I think it’s tremendously important,” UCLA’s Berger said. Chohfi’s work, he said, “is quite a feat.”

Chohfi’s dream now is to return to Maranpampa and use modern archeological techniques that were not available when Machu Picchu was discovered three quarters of a century ago. He hopes that when he is through, the world will have a better understanding of a people who made the most of what they had.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.