Silence in South Africa

- Share via

The strike at the General Motors plant in Port Elizabeth, South Africa, has been suppressed with the help of police guard dogs and whips and what appears to be the quiet indifference of management both in Detroit and at the South African subsidiary. The event does not bode well for the disinvestment of this, one of the largest U.S. business operations in South Africa.

There are, at best, serious questions that GM has chosen not to address, insisting that negotiations now under way preclude offering details. But principles, not details, are at stake, and the silence of GM on those principles, after its years of leadership on racial equality in South Africa, is cause for concern.

“We have every reason to expect that our social programs, to a large extent, will be continued,” a GM spokesman told us. That contrasts with the specific way three other giant American industrial firms are talking about their withdrawals from South Africa.

Eastman Kodak has decided to terminate all operations in South Africa on the ground that there no longer are reasonable hopes for an end to apartheid in the foreseeable future. Kodak will end all commercial contacts with a payment of severance to its 466 workers. IBM and Coca-Cola will sever direct ties and, like GM, create new entities, owned by South Africans but supplied by the American corporations. But, unlike GM, they have made commitments at the outset of negotiations to assure a financial role for non-whites in the new enterprises. Coca-Cola is selling its interests to black South Africans in a bold initiative to enlarge multiracial participation in the economy. IBM is creating a new entity in South Africa established “for the benefit of the employees,” which means that the 15% of the 1,500 employes who are of the black majority will share proportionately in the ownership of the new company with those of other races.

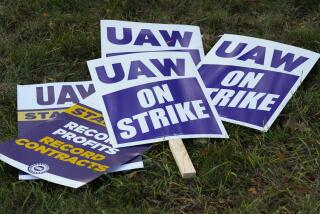

A spokesman for General Motors could say only that negotiations are proceeding to sell the South African interests to local investors headed by GM management--a management, incidentally, that includes no blacks or persons of mixed race. It was the obscurity of GM’s plans to protect workers, or to assure a financial share for blacks, that had triggered the strike at Port Elizabeth by the National Automobile and Allied Workers Union. Management remained aloof, by all accounts, insisting that there would be no clarifications until the workers were back. Now most are. And the clarifications are awaited.