Hepatitis Outbreak Delays Novel Cancer Therapy Test

- Share via

A widely publicized trial of a novel immune system treatment for advanced cancer patients has been disrupted and set back by many months because of an unusual epidemic of hepatitis A among some of the early participants in the nationwide experiment.

The source of the nonfatal outbreak appears to be infected blood that contaminated the nutrients used to stimulate the patients’ own white blood cells to fight their tumors, according to Dr. Robert Wittes of the National Cancer Institute (NCI).

After the freak epidemic was discovered, officials interrupted the study and launched an investigation before allowing treatment to resume for the patients. The probe is still going on and no new patients are being enrolled in the experimental trials.

But neither the delay nor the outbreak is expected to affect the scientific validity of the “interleukin-2/killer cell” trials. All of the infected patients recovered.

The disruption comes amid reports that the highly touted immunotherapy is not living up to initial expectations and is sometimes causing serious side effects, including heart attacks, severe fluid accumulation in the lungs and temporary coma. Two patients have died from the treatments, according to Wittes.

The hepatitis outbreak was discovered in August, and NCI officials in September, without making a public announcement, stopped enrolling patients at the six participating medical centers, which include the City of Hope in Duarte and the University of California, San Francisco.

Those trials are expected to resume by mid-December or early January, but no date has been set, Wittes said. Several hundred patients were to have been treated this year, but fewer than 100 had been enrolled at the time of the outbreak.

Potential patients, who have been informed of the suspension, are being offered alternate treatments.

Institute’s Trials Continue

Interleukin-2/killer cell trials at the cancer institute itself, involving more than 100 patients, are continuing because the blood that NCI used apparently was not contaminated.

In all, 32 out of about 90 patients in the six-center study received contaminated killer cells and 12 developed hepatitis A infections. But only five of them experienced mild symptoms of liver inflammation, such as nausea, fatigue and jaundice, Wittes said. Two transmitted the infection to their spouses.

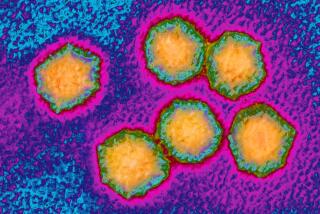

The epidemic surprised researchers because the hepatitis A virus is almost exclusively transmitted by fecal contamination of food or water, according to Dr. Isaac B. Weisfuse of the federal Centers for Disease Control, who is investigating the outbreak.

The virus, unlike the equally common hepatitis B virus, is almost never transmitted through contaminated blood, and therefore donated blood is not tested for hepatitis A, he said.

About 25,000 cases of each of these forms of hepatitis are reported in the United States each year.

“This is major nuisance, but not a major stumbling block to the development of the treatment,” Wittes said in a telephone interview from Bethesda, Md. “None of us had any ethical qualms about stopping the study until the problem was resolved.”

Overreaction Suggested

But at least one of the investigators believes that the NCI has overreacted, noting that the transient symptoms of hepatitis A are minor compared to the toxic side effects of the experimental cancer therapy and to the incurable tumors themselves.

“Some of the patients would have been willing to take the chance of getting hepatitis A in order to get the therapy,” said Dr. James Mier of the New England Medical Center in Boston. “I would have been willing to take the chance myself.”

Another investigator said it was a “reasonable judgment” to stop the trials, given concern about transmitting hepatitis to family members and the possibility that the contaminated blood contained other viruses as well.

“This was not a major disaster; the study could have continued,” said the investigator, Dr. Charles A. Coltman Jr. of the Audie Murphy Veterans Administration Hospital in San Antonio. “A physician from Alabama who is a prime candidate for the treatment calls me every two weeks wondering when this is going to start up again.”

The treatment, developed by Dr. Steven A. Rosenberg, chief of surgery at the NCI, uses the protein interleukin-2, a natural immune system booster, to transform in the laboratory a patient’s own white blood cells into activated tumor-killing cells, called “LAK” cells. Such cells are then reinfused into the patient’s bloodstream through a vein, along with massive doses of interleukin-2.

Initial Treatment

At the NCI, Rosenberg initially treated 25 patients; one patient’s tumor disappeared and tumors in 10 other patients shrunk by more than 50%, commonly defined as a partial response. After Rosenberg published these results in the New England Journal of Medicine last December, the cancer institute received thousands of calls from patients who also wanted to be treated.

In February, the cancer institute started the national trials to see if Rosenberg’s results could be confirmed.

In those national trials, there has been one complete response and three partial responses in 30 kidney cancer patients, and five partial responses in 29 melanoma patients, according to the Oct. 24 issue of The Cancer Letter, a private newsletter for tumor specialists published in Reston, Va.

In the meantime, Rosenberg has expanded his own trials. In all, he has treated 36 kidney cancer patients, with four complete and seven partial responses, according to the newsletter. He has also treated 25 melanoma patients, with one complete and five partial responses.

Rosenberg declined in an interview to discuss his study because his updated findings have yet to be presented at medical meetings or published in medical journals.

“There are definite and valid responses but it appears that the initial response rates are not going to be matched,” said Dr. John Mendelsohn of Memorial-Sloan Kettering Hospital in New York. He is a member of the board of scientific counselors to the NCI’s division of cancer treatment, which is monitoring both sets of trials.

Learning Period

Mendelsohn predicted that it would take “two to three” years to learn conclusively if Rosenberg’s treatment is prolonging the life of patients or decreasing their suffering, compared to other therapies, such as chemotherapy, radiation or surgery.

The immunotherapy so far appears to be most effective for patients with kidney cancer or melanoma, a skin cancer that can spread rapidly throughout the body, according to Dr. Anthony Rayner of the UC Medical Center, San Francisco, an investigator in the study. Other treatments usually fail against advanced cases of these tumors. “The level of enthusiasm for this treatment is still very high,” he said.

The hepatitis A epidemic was discovered in August as a result of routine follow-up of abnormal “liver function” blood tests on two patients at the New England Medical Center. Within days, additional cases were detected at the other medical centers.

NCI officials were initially uncertain about how to proceed. The cancer treatments were stopped, resumed for a few days and then suspended indefinitely, Wittes said.

Patients, family members and some health care workers were immediately tested for exposure to the virus; some received gamma globulin shots in an attempt to prevent additional hepatitis cases from developing. Further treatments for many of these patients are continuing.

Most of the infected patients had very mild symptoms. “It is hard to distinguish the symptoms of low-grade hepatitis from the fatigue which goes along with the treatment,” said Rayner of UC San Francisco. “One 18-year-old kid who had a dramatic response to metastatic melanoma went camping (while he had hepatitis).”

Rosenberg would not say if any cases of hepatitis had occurred in the ongoing trials at the cancer institute.

Suspected Source

The Centers for Disease Control’s Weisfuse believes the likely source of the contamination is the human blood serum contained in the laboratory solution used to grow patients’ killer cells.

“We have epidemiologically ruled out all the other ingredients the patients were exposed to,” he said. But Weisfuse added that he is not optimistic that it will be possible to reconstruct exactly how the contamination occurred.

The growth solution was prepared in large batches by Whittaker M.A. Bioproducts of Walkersville, Md., according to several sources. Whittaker bought the blood serum for the growth solution from several companies that collect plasma from paid donors. Each week, serum from about 80 blood donors had to be obtained to prepare the 1,000 liters of growth solution required by the six medical centers, according to Mier of the New England Medical Center in Boston.

“The (contaminated) sera was donated many months ago. It does not necessarily exist,” Weisfuse said.