The Spirit and the Flesh: Sexual Diversity in American Indian Culture <i> by Walter L. Williams (Beacon: $21.95; 333 pp., illustrated)</i>

- Share via

The following is a public opinion survey: Would you like to read a book on the American Indian berdache? Not particularly, you say? I’ll rephrase the question. Would your interest be piqued by a book about effeminate men who have sex with other men and at the same time are respected family members, teachers of children, and spiritual leaders of their communities? If so, this book is for you, as well as for anyone else with an interest in gender and sexuality.

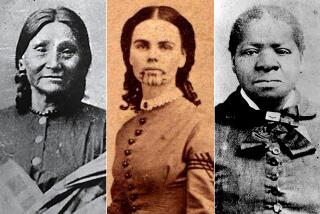

The berdache institution was widespread in the Americas when the Europeans put in to shore. Needless to say, it horrified the new arrivals who gave it a name, derived from Persian, meaning male homosexual prostitute. As shocking to the Europeans as the berdaches’ sexual practices, was the religious meaning American Indians attached to these figures. Walter L. Williams, a historian and anthropologist at the University of Southern California, takes the title of his book from a Jesuit missionary who wrote, “It was pretended that this custom comes from . . . religion. . . . If the custom I speak of had its beginnings in the spirit, it has ended in the flesh.”

Disentangling American Indian thought and practice from European perceptions and prejudices is a challenging task. Williams develops a persuasive interpretation of the diverse historical and ethnographic sources on the berdache. At the same time he provides a valuable review of recent work on the subject. The result is a very readable book with which all future work on the berdache must come to terms.

Presuming that the sexes are “opposed,” Western observers encounter trouble in categorizing the berdache. American Indian informants have insisted that the berdache is a mixture of male and female. Early scholars interpreted this to mean that berdaches were physical hermaphrodites. Once disabused of this notion, many viewed the berdache as a man who “becomes” a woman.

Williams regards the berdache as an intermediate or third gender. Hence, masculine-identified men who have sex with a berdache are not in cultural terms engaging in a homosexual act, but a “heterogendered” one. Yet “homogendered” sexual acts among men seem to have been tolerated as well. (While admitting the importance of understanding comparable acts among women, Williams pleads a lack of information.) In contrast to dominant white culture that defines gender identity in terms of sexual preference, Native American peoples, Williams claims, have traditionally not considered a man’s masculinity impugned by sexual acts with either berdaches or masculine men.

Of greatest surprise to anthropologists who read this book will be Williams’ account of the modern berdache. Ethnographers in this century have portrayed the berdache institution as dying or defunct. Williams, however, drawing on his own field research since 1982 in a number of tribal areas, establishes that berdaches are alive and well among traditionalist American Indians. He provides fascinating glimpses of modern-day politics surrounding the berdache--such as an alliance between elderly traditionalist and young gay Native Americans in support of a berdache revival despite disapproval by their middle-aged Christian relatives.

Williams also traces an alliance between gay activists and American Indians. For nearly a century, gay rights advocates have taken an interest in the berdache as part of their effort to legitimize homosexuality by showing its acceptance in other cultures. Williams explores not only the interest the berdache has held for gay rights advocates, but also the impact of the gay consciousness movement on young American Indians today.

In the course of his study, Williams “comes out” to his readers as a gay researcher whose information derives not only from interviews and archives, but also from intimate experience with both berdaches and men in Native American communities.

In citing his personal experience, Williams conforms to the standard mode of social science discourse whereby the “objective” observer reports what is going on “out there.” By doing so, he leaves his “objectivity” more open to challenge than might have been the case had he directly addressed the implications of his personal relations for the study. One senses from veiled hints of his spiritual as well as sexual involvement with his informants that Williams could write a sensitive account of how he has come to know what he knows.

I would also welcome a more critical appraisal of the degree to which berdaches (and by extension, “homosexuals” and “heterosexuals”) are born or constructed. Feminist scholars have emphasized the cultural malleability of human gender. Williams documents great malleability, yet in the end adopts a more “essentialist” position. His justification for doing so is reasonable: “If behavior is socially constructed, of what is it constructed?”

But his argument appears to be driven by a desire to assert the “naturalness” of homosexual practices as a defense against a homophobic society and by a reluctance to imply that American Indian culture is responsible for promoting behavior that the dominant society regards as deviant. In Williams’ future work, I hope he will address more fully both the political and intellectual dimensions of this debate.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.