Bread and Stones <i> by Ellen Alexander Conley (Mercury House: $16.95; 247 pp.) </i>

- Share via

Much of our recent fiction has taken as its subject matter post-modern life in the United States, with its obligatory cast of disaffected characters. The range of interests in these novels and stories rarely exceeds self-involvement. Love affairs, individuals’ isolation from society, the meaninglessness of personal gestures of all kinds dominate the fictional landscape. But alongside this increasingly localized literature, a canon of global literature continues to paint a larger picture of the world.

Just as the late ‘60s and early ‘70s saw writers turning their attention to Vietnam, it is no coincidence that in the ‘80s, our fictional territory has expanded to include Central and South America. Margaret Atwood’s “Bodily Harm,” Denis Johnson’s “The Stars at Noon” and Toby Olson’s “The Woman Who Escaped From Shame” are just three recent novels among several that have chosen to address a wider American geography and predicament. So does Ellen Alexander Conley’s third novel, “Bread and Stones.”

Conley’s story starts in New York, where we meet Liat Bloom, a doctor who’s trying to balance a life as a wife and mother with her career as a medical school instructor. The family, as usual, is winning out. But what’s not usual is that Liat decides to take a leave of absence from New York, her job, her family--to rekindle some earlier sense she had of herself before marriage and before her induction into the bureaucracy of medicine. She returns to Schweitzerville, a clinic in the bush country of Colombia, where once she spent time in the Peace Corps.

At Schweitzerville, we are introduced to two native Colombians, who along with Bloom, are the central characters of the story: Dr. Marques de Botero, the head doctor, and a nurse-midwife, known simply as Merta, who is also a revolutionary. During the months she spends at the clinic, Liat falls in love with Marques, bringing on a kind of personal crisis, and later, her friendship with Merta ends with the woman’s brutal murder by government troops, bringing on a crisis of conscience and her own expulsion from Schweitzerville.

Of the two stories, the love affair is the less interesting, perhaps because it could have been set anywhere and because Conley telegraphs Liat’s interior life, robbing it of the specificity that would compel us. The larger human story is what carries the book: the local people, their poverty, the doctors’ daily ministrations to their needs. A scene in which Liat performs a life-saving Caesarean and one in which Marques puts a rabid boy to sleep the way we would a dog, contain the best writing in the book. Otherwise, the prose is serviceable, occasionally marred by such awkward metaphors as “white parrots nested on the barren sticks of trees like toilet paper. . . .”

That Liat is a character with a social vision that goes beyond her family and her career and an interest in helping less fortunate people is one of the real pleasures of this novel. That her own role as a middle-class North American places her outside the predicament of the people she treats is both the philosophical core of the novel and ultimately its biggest problem. One never expects Liat to take an active role in the revolutionary activity, even when propelled to do so by her friend’s death, and when at the end of the book, she dares to smuggle a relic out of the country, it is at best a symbolic act. One can’t help but feel by the novel’s resolution--in which Liat must choose between remaining in Colombia with Marques and continuing her work with the poor or returning to her life and family in New York--that it is a personal resolution only.

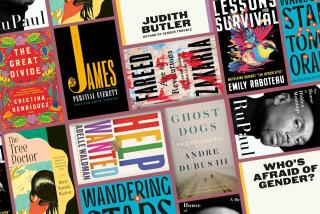

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.