Hats Off to Bolivians--From Derbies to Helmets, They’re Tops

- Share via

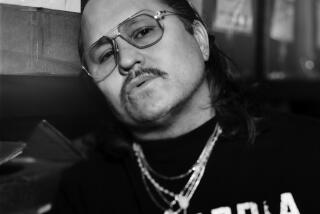

JATAMAYU, Bolivia — When Severino Vela got married recently, he wore a montera , a black leather hat patterned after the 16th-Century helmets of Bolivia’s Spanish conquerors.

The bride also wore a hat. It had a flat, black cloth brim, two raised points on top, embroidery of green, red and black threads and an assortment of silver beads and shingles.

Adult wedding guests appeared at the church in leather or felt headwear of different styles favored by the Quechua Indians who live around here. Children under 18 wore knitted wool hats.

Traded for Sheep

Hats are so common and varied in Bolivia that Vela, a 37-year-old Quechua farmer, finds it good business to make them on the side. He often trades a new hat for a sheep.

“I learned from a master craftsman who died several years ago,” Vela told a visitor as he fashioned his wedding hat from leather that had been dyed with fermented corn juice and rusted iron.

Elsewhere in Bolivia, people cover their heads with tin, plaster, rabbit hair, feathers, straw, alpaca and tortora reeds. South America’s poorest country is rich in hat styles--more than 100 for a population of 6.4 million.

Bolivians have popularized a derby for women. They also make a Stetson known locally as a “J.R. Dallas,” because it resembles what J.R. Ewing wears on the universally popular television series “Dallas.”

Source of Identity

“I don’t know of another region in the world that has such a variety of hats,” says Gunnar Mendoza, director of the National Archives in Sucre, the colonial capital. “Aside from its use as part of an outfit, the hat serves as a way for people to identify themselves.”

While urbanization and the covered automobile have put hats out of fashion in many other places, the demand for them in Bolivia remains steady. As a result, hat-making is a thriving business, from Severino Vela’s busy shop at home to the industry-leading Charcas Glorieta factory in Sucre.

One reason is Bolivia’s high altitude in the Andes, where the sun’s rays are more intense and few shade trees grow, making hats a necessity for many. Another is that the open-backed truck remains a popular means of transportation. A third factor is the survival of traditional costumes, hats and all, among Bolivia’s Indian majority.

President Victor Paz Estenssoro, like other members of the country’s European-descended elite, generally shuns hats. But during his election campaign last year, he wore a variety of colorful hats on trips to Indian farming villages and won most of the rural vote.

Women in Derbies

The feature of Aymara Indian women that most strikes visitors in La Paz, the Bolivian capital, is their derby.

In English, the derby is referred to here as a bowler, the name of the English manufacturer that introduced them to neighboring Argentina in the 19th Century. But Bolivians call the hat a bombin .

Aymara women, who dominate the city’s retail trade, wear black, brown or gray bombins while selling fruits, vegetables, home computers and compact discs. In other countries, it is a man’s hat, but men here wear other styles.

According to one story, a shipment of felt bowlers arrived in Bolivia by mistake, and an enterprising salesman convinced Aymara women that wearing them would guarantee fertility.

As the idea caught on, a model made of rabbit hair by the Borsalini factory in Italy became a status symbol among wealthier Aymara women.

Selling for $75

One store, which has been importing Borsalini bombins for 30 years, now sells four to six a day, for $75 each, according to Sonia Barriga, the store manager.

But the Borsalini factory, which manufactured hats exclusively for the Bolivian market, recently closed, and much of the demand is now expected to be filled by Charcas Glorieta, a Bolivian hat-making company with a history as colorful as some of its hats.

The factory in Sucre was founded in 1929 by Princess Clotilde Urioste de Argandona, a Bolivian philanthropist who was given her title by Pope Leo XIII in the late 19th Century when her husband was ambassador to the Vatican.

With inherited wealth, she built a castle in Sucre, surrounded by Venetian-style canals, gardens and a small zoo, and started the hat factory to provide jobs for the people.

500,000 Per Year

Today, the factory produces 500,000 hats or unfinished felt hat casings per year, supplying about half the Bolivian market. At least 2,000 hatmakers in Bolivia, Peru and Chile buy the casings and mold them into finished bombins that sell for $10 to $20 apiece.

Most of the steam-powered machines at Charcas Glorieta date to its founding. Manned by 160 employees, they turn Bolivian, Uruguayan and Argentine wool into 35 different hat forms, some based on U.S. and European designs.

Spare parts and molds must be made by hand because the factory that built the machinery no longer exists, says Mario Nosiglia Biella, who has managed the plant since immigrating from Italy in 1948.

“In my hometown of Sagliano-Micca, there used to be nine hat factories,” he says. “Now, there is only one. Twenty years ago, everybody in Europe wore a hat, but with the evolution of the automobile the use of hats has dropped considerably. Hat factories throughout the world are closing.”

But Charcas Glorieta is unable to keep up with demand in Bolivia. So, it has just purchased the Italian hat company Panizza’s entire factory with a $2-million credit, $600,000 of it from the U.S. Agency for International Development.

Factory Expanding

Nosiglia says the expansion will double the factory’s output to 1 million felt hats per year while enabling it to make 60,000 rabbit-hair hats. He says 20,000 rabbit-hair hats will be exported to Italy for Panizza’s former clients.

The enlarged factory will benefit farmers, who will supply the hair of at least 50,000 rabbits a year and wool from 10,000 sheep, according to company plans. “The economic impact will be extraordinary,” Nosiglia says.

Charcas Glorieta already makes thousands of “J.R. Dallas” hats that sell here for $15 apiece, as well as traditional hats for nearly every region of Bolivia.

For example, residents of Tarija, near the Argentine border, wear hats patterned after those worn by their colonial ancestors from Andalusia, Spain. People in Jatamayu, in the central highlands around Sucre, prefer the helmet-like hats such as Vela’s.

Legend of the Ribbon

In Cochabamba, a city of 300,000 between here and La Paz, Quechua Indian women wear white hats made from felt and plaster of Paris, decorated with a black ribbon.

According to legend, a young, unmarried Quechua woman there was publicly reprimanded by a Roman Catholic priest for living with her boyfriend, a practice common among Indian couples intending to marry. For penance, she was made to wear a black ribbon around the base of her hat.

The next day at Mass, all women present wore black ribbons, much to the priest’s chagrin, and the style stuck.

“The hat in Bolivia is not just to protect oneself from the sun,” says Harold de Faria Castro, a Bolivian author on the subject. “It is the most important piece of an outfit. The hat accompanies an Indian while he sleeps and is always on his head, whether it rains or shines.”

“The reason the hat is so important,” he adds, “is because it is understood to be intimately tied to the head, and this is the most sacred part of the body and spirit.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.