Firm Rolls Up Record Income, Sales by Making Cast-Aluminum Wheels

- Share via

LOS ANGELES — Who says you can’t get rich reinventing the wheel? Look at Lou Borick, chairman of Superior Industries in Van Nuys.

Forty years ago he started out with $3,000, mostly borrowed from his sister, selling plastic car seat covers. But it wasn’t until 1974 that Borick made the big time when he nailed down his first contract to supply cast-aluminum wheels for the Ford Mustang.

“The first time Ford’s people came out here, they looked at me, shook their heads and said, ‘You’ve got a long way to go, pal,’ ” recalled Borick, a gruff 63-year-old. “But we got our quality up, and we convinced them.”

He also convinced General Motors and Chrysler. Now, 74% of Superior’s sales come from original equipment sales to the Big Three auto makers, primarily from those snazzy cast-aluminum wheels, which have been gaining dramatically in popularity because of their style and light weight.

Paying Off

It’s all paying off for Louis L. Borick and Superior. Last month the company announced record results for 1986 as net income jumped 17% from the previous year, to $8.5 million, while sales were up 14%, to $149 million. Superior’s stock closed at $15 5/8 Friday on the American Stock Exchange.

As for Borick, he and his ex-wife, Juanita, through a special voting trust own 30% of Superior’s common stock, worth nearly $28 million. On dividends alone, they took home $415,000 last year. There is also Borick’s $275,000 base pay, and he is entitled to bonuses. He and his three children also received about $850,000 in rent last year from office and manufacturing space leased to Superior, at rates that real estate analysts said are near or below market price.

The only real threat to Borick’s continued prosperity is an attempt by the United Auto Workers to unionize his Van Nuys plant. For now, that battle is stalled in a labor court.

In the meantime, Borick keeps concentrating on those hot wheels. Aluminum wheels are one-third lighter than steel, so they improve fuel efficiency, which pleases consumers. The auto makers like the wheels because they offer high profit margins. The Big Three car makers charge $400 to $600 for a set of four aluminum wheels as optional equipment. Superior sells those wheels wholesale to the Big 3 for as little as $160.

Analysts says the aluminum wheel market should continue to grow, even if car sales dip. That’s because manufacturers are increasingly making aluminum wheels standard equipment, not only in sporty cars like the Chevrolet Corvette, but in Dodge half-ton pickups and luxury Lincoln Town Cars.

Only a few foreign car companies such as Mercedes-Benz, Volvo and Nissan make their own cast-aluminum wheels. The American car companies prefer to use lower-cost outside suppliers such as Superior. Borick’s company is the biggest of a half-dozen wheel makers in the United States, analysts said.

“The wheel sales are going to continue outpacing car sales by raising market penetration,” predicted analyst Todd Berko, who follows Superior for Drexel Burham Lambert. “They can ride on their solid customer base for at least a couple of years.”

For Borick, it is a far cry from the frigid St. Paul, Minn., office where he started. A car nut ever since he paid $50 for a 1935 Pontiac just after World War II, he started selling the plastic seat covers after receiving his degree in industrial engineering from the University of Minnesota.

Sun and Surf

By the time he was 32, his firm had sales of $2 million a year. But seeking sun and surf in Southern California, he sold the business and started from scratch here, this time marketing insect screens to keep bugs from splattering windshields.

He called the new business Superior Industries. It was rough going in the early years: Borick discovered the bug problem isn’t as bad in California as it is in the Farm Belt. Sales the first year were only $27,000. “I was too dumb to realize what I was getting into,” he said. But Borick moved into other products, such as car springs and seat belts, and he hit $1 million in sales by 1961.

Superior kept growing through the 1970s. Nevertheless, as a producer of equipment for people who tinker with their cars, the so-called “aftermarket,” Superior’s business was never huge or predictable. Superior, like other auto suppliers, remains vulnerable to the broad swings of the new car market. In the 1979 and 1980 slump in new car sales, for example, Superior lost $3.4 million.

But the aluminum wheels have helped pull the company back. Although Superior still makes products for the aftermarket, such as chrome exhaust pipes, license plate frames, curb feelers and “E-Z Slider” replacement rear windows for pickup trucks, its aftermarket sales are up only 16% since 1983. In the same period, Superior’s cast-aluminum wheel sales have jumped 112%. At Superior’s six manufacturing plants, it takes about eight hours to melt the raw aluminum and cast it. But, if a cavity or crack appears in the wheel, it must be melted and recast. The company attributed its lower-than-expected 1984 earnings to high scrap rates.

There’s always the threat, of course, that some new manufacturing technique could challenge Superior’s products. One threat could come from aluminum wheels that are stamped instead of cast, or wheels made of composite materials, just now being tested. But, even if these products gain favor, it will take several years of engineering before they are marketable.

‘A Tough Business’

“It’s a tough business to get into,” said Superior vice president for finance, R. Jeffrey Ornstein. “There’s a big investment in technology. To make the wheels, you have to know what you’re doing, coordinating time and temperature. A high scrap rate will kill you.”

It’s because of these equipment problems, Ornstein said, that Superior has so little competition.

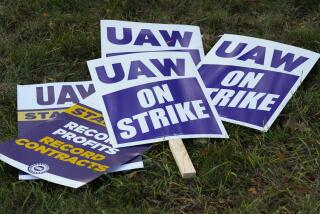

Its main roadblock could be the United Auto Workers. In August, 1984, the UAW won a representation election among Superior’s 1,300 workers at the Van Nuys plant.

But Superior contested the vote with the National Labor Relations Board, charging that organizers from UAW Local 645, which also represents the Van Nuys General Motors plant, threatened some employees and bribed others with $5 bills at the polls.

The union has denied the allegations, counter-charging that during the election campaign Superior threatened to fire some employees and illegally interrogated them about union activities.

The case has been before the National Labor Relations Board since then. In January, 1986, the NLRB’s Westwood office recommended to the executive secretary’s office in Washington that the group certify the vote, but the case is still pending there.

No Talks Held

Because a union cannot gain recognition as the workers’ bargaining agent until election results are certified, negotiations toward a new contract have not been conducted.

The union accuses the NLRB of dragging its heels.

“It’s complicated,” said David Parker, director of information for the NLRB. “We’re trying to give it the airing it deserves. Jeez, we’ve already got more than 10,000 pages worth of hearing records.”

In the meantime, Superior’s blue-collar workers receive wages and benefits totaling $14 an hour, whereas GM’s union workers get about $25.

That difference is critical to Superior’s success. With lower wage-and-benefit packages, Superior remains appealing to the auto makers because it can manufacture the wheels far cheaper than Detroit can.

If the UAW forces Superior to raise wages and install costly improvements in work conditions, such as more fans and exhaust systems to cool the foundry area, the company figures it will lose its competitive edge.

Superior is in a low-margin business. Even in a good year such as 1986, Superior showed a profit of less than 6 cents per dollar of sales.

But the UAW contends that improvements in work conditions at Superior are long overdue. The Van Nuys plant is running at full steam, operating on two 10-hour shifts, 5 1/2 days a week.

It adds up to a 55-hour workweek in a hot temperature for Superior’s blue-collar employees. The UAW has charged that Superior fires workers who refuse to put in the long week. Victor Barrios, a UAW organizer who worked at Superior two years before quitting last November, said foremen physically bully workers to raise productivity. Superior denies the charge.

But Superior’s Ornstein, who cites the declining membership in the UAW as a whole and the continuing bitter split over GM work-rule changes at Local 645 in particular, said he isn’t too worried about negotiations with the UAW should the plant’s 1,300 employees unionize.

“I don’t really see what they can bring to the table,” Ornstein said.

Strike Benefits Mentioned

Mark Masaoka, a laid-off worker from the GM factory who is heading the organizing drive at Superior as a volunteer, countered that, with a union, Superior’s workers could walk out and receive strike benefits.

If that happened, Ornstein said, Superior could simply close the Van Nuys plant and shift production elsewhere. In the last two years Superior opened plants in Ontario, Canada, and Fayetteville, Ark., to increase its capacity and move operations closer to its Midwest customers. The new plants have not been targets of UAW organizing efforts.

Although the new plants are struggling to raise their output, the Van Nuys plant continues to operate at full capacity. Meanwhile, Ornstein said, profit margins must remain relatively low to keep Superior’s auto-maker customers.

“We could charge the heck out of everything, then find ourselves with nothing but our aftermarket business down the road,” Ornstein said.