Filipinos Guard Isles : Nations Vie for Specks in S. China Sea

- Share via

PAGASA, Philippine-occupied Spratly Islands — This tiny speck of sand and coral in the South China Sea hundreds of miles from anywhere hardly looked like the object of international conflict.

A Stevie Wonder tune blared from a portable tape player beside five rusty combat tanks, where a rooster searched for shade. A Philippine marine lazed in the blistering morning sun, dreaming, he said, of “anywhere but here.”

More marines were out on the reef in T-shirts and shorts, collecting seashells and fishing for octopus, “just to keep from going completely crazy,” their commander, navy Lt. Luis Panganiban, said. Another group of soldiers was in the arts-and-crafts shed, gluing together driftwood and seashell souvenirs of their three-month tour of duty in what must be one of the world’s loneliest military outposts.

Protecting a Claim

To the few Filipinos who know about them, these soldiers are performing some of the most patriotic and psychologically taxing duty in the Philippine armed forces: They are protecting the Philippines’ claim to what may one day be some of the world’s most strategic real estate.

“It is a game of finders-keepers,” Philippine navy Lt. Cmdr. Tomas Estrella told a visitor recently. “If we leave this place today, some other country will occupy it tomorrow.”

At issue is an archipelago of 22 tiny and widely scattered islands, reefs and shoals that the Filipinos call Kalayaan--the native word for Freedomland. The rest of the world knows it as the Spratly Islands.

The other governments involved, besides the Philippines, are those of Vietnam, Taiwan, Malaysia and China. They all claim ownership of an island chain that is not only strategic but a potential economic windfall as well.

Enemy is Boredom

A recent, rare visit to the largest Philippine-occupied island revealed that beneath the serene, tropical veneer of Kalayaan, there is, indeed, a strange war going on, one that ranks among the world’s least-known yet most bizarre: In 30 years of conflict, not a single hostile shot has been fired. Instead, one senior naval officer said, “Our worst enemy is boredom.”

The arena of the conflict is a vast expanse of water in the South China Sea, halfway between the western Philippines and the coast of Vietnam, where the Soviets now use the former American naval base at Cam Ranh Bay.

Yet the battle is more than a psychological game of strategic checkers in which islands and reefs are the pieces. Beneath the surface of the surrounding waters are believed to be huge deposits of minerals, marine resources and potentially vast reservoirs of oil.

“This is the last frontier,” said navy Capt. Ruben De la Cruz, the regional naval commander. “It has vast, untouched, unexploited natural resources, both on land and under the sea.”

All of which may explain why so many countries have tried so hard for so long to take as many of the islands as they can.

According to Philippine military intelligence reports, the Philippines now occupies eight of the islands; the Vietnamese navy has possession of 10 others, and Taiwan controls one--with 80 acres, the largest in the group. Malaysia occupies two still-submerged reefs, its armed sailors living in huts on stilts just above the ocean surface.

To further complicate matters, several of the islands also are claimed by at least one private citizen, an 86-year-old Filipino fisherman who says that he discovered them 30 years ago but was evicted by former President Ferdinand E. Marcos when Marcos declared martial law and occupied the islands in 1972.

The fisherman, Tomas Cloma, is petitioning the government of President Corazon Aquino to restore his personal sovereignty.

“I know this whole things seems a little crazy,” said Philippine navy Capt. Francisco Tolin, De la Cruz’s deputy and commander of the naval task force overseeing naval operations in Kalayaan. “But it’s dead serious. . . . This is our front line of defense for our country and part of our sovereign territory. And when our men come back, we usually give them a decoration for courage.”

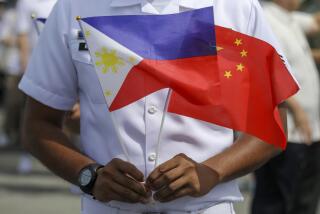

Flags Mark Claims

Tolin spoke from a war room 300 miles away, on the nearest major Philippine island, Palawan. Beside him, on a 10-by-20-foot wall map of the South China Sea, each island of the archipelago was marked by the flag of the nation occupying it.

For Tolin and the Philippine armed forces, Kalayaan is an important military staging point. Its history and the other nations’ claims to it are largely immaterial. But the background of the conflict is at least as unusual as the conflict itself.

American naval forces apparently were the first to use the islands during World War II. They built a lighthouse on one, concrete bunkers on others, and occasionally stopped for provisions at the few islands having lakes and freshwater wells.

The earliest record of civilian population on the islands was a report by Morton F. Meads, a former enlisted man in the U.S. Army who asserted that he had “discovered” the islands in 1945 when he sailed out of the southern Philippine island of Jolo in an ancient canoe.

After two days at sea, Meads later reported to military authorities in Manila, he landed on the largest of the islands, which he said was called The Kingdom of Humanity-Freedomland. He said it was ruled by an American “king” named Willis Alva Ryant and his executive secretary, Victor Anderson.

Appointed by ‘King’

Although Meads’ story was never verified, he announced that King Ryant had appointed him the island’s consul and commercial agent, and he spent the next several months ordering postage stamps printed in Manila that depicted the mushroom cloud of an exploding atomic bomb and the word Freedomland.

Meads’ activities quickly raised suspicion. The Philippine military began an investigation, aerially photographing all the islands and discovering no inhabitants. Ultimately, Meads was arrested and charged with both civil and criminal fraud, but all of the cases were later dismissed.

Public interest in the islands soon died down, but not before the Nationalist Chinese government on Taiwan announced that the islands, although more than 1,000 miles from Taiwan, were part of its sovereign territory and that it would fight any Philippine claim of ownership. Taiwan forces occupied the largest of the islands soon after.

About 10 years later, the biggest recorded controversy over the tiny archipelago erupted when Tomas Cloma, then a wealthy fisherman from Manila, laid claim to what he, too, called “Freedomland,” which he said he discovered during fishing expeditions between 1947 and 1950.

On May 15, 1956, Cloma sent to the Philippine secretary of foreign affairs a mimeographed map of his islands, together with what he entitled, “Notice to the Whole World.” It declared that the territory, “composed of islands, sand cays, sand bars, coral reefs and fishing ground, with a total area of about 64,976 square nautical miles” was his, and his alone.

‘Slight Case of Imperialism’

At first, the Manila press and newspapers worldwide treated the affair with humor. Cloma was jokingly dubbed “The Admiral,” a nickname that stuck, and “a modern Magellan.” One columnist wrote that Cloma was suffering from “a slight case of imperialism.”

But the international debate that Cloma’s “Notice to the Whole World” touched off soon pitted the Philippine government not only against Cloma but also against Taiwan, Vietnam, Malaysia and China, all of which officially declared the islands were theirs.

At one point, even France claimed sovereignty, by virtue of its earlier colonial control over Vietnam, a claim the French said was bolstered by a marker discovered on the largest of the islands that bears the words, “Isle de France, April 25, 1933.”

On Aug. 30, 1956, a Vietnamese government spokesman announced in Saigon that a Vietnamese naval party had hoisted that nation’s flag on what he called Spratly Island, registering that nation’s first known claim to Freedomland.

Eventually, the controversy died down, primarily because Cloma decided to abandon his public proclamations and quietly begin recruiting what he called “immigrants” to his new nation.

Juan Arreglado, a friend of Cloma’s and a former Philippine ambassador to Spain, recalled in a recent interview that Cloma persuaded more than 100 Filipino fishermen to migrate to Kalayaan between 1964 and 1972.

Marcos Ordered Survey

During that time, though, then-President Marcos had ordered his military to survey the islands with U.S. technical assistance. Based on the strategic location of Kalayaan, and amid reports that the Taiwan navy was firing on the fishermen, Marcos ordered the military to evacuate civilians from the islands. He even jailed Cloma for two months for “impersonating an admiral.”

In the 1970s, the Vietnamese began occupying many of the islands that the Filipinos had overlooked. In the beginning, soldiers who were stationed in Kalayaan at the time now recall, the Vietnamese sailors would occasionally visit the Philippine-occupied islands for games of basketball, but the practice ended when South Vietnam fell to North Vietnam in 1975. It was also about that time that the Philippine armed forces began taking the strategic value of the islands far more seriously

Although the Philippine soldiers now occupying the islands understand their strategic importance, they are still mystified as to why anyone would want these barren bits of land. No civilians live on the islands. Besides the soldiers, there are only sea gulls and a few crumbling buildings and huts. Life for the Philippine military in Freedomland today is, to say the least, not great duty.

On the smallest Philippine-occupied island of Patag, which is nothing more than a barren sand bar of less than four acres in all, the resident contingent of 10 Philippine marines must sleep in their life jackets in stilt houses because their island disappears once a day at high tide.

Island Changes Shape

For drinking water, the marines must catch logs that drift ashore, use them for firewood to boil seawater into steam, and then collect the condensation in a second pot. Aside from the military radio they use to relay daily intelligence reports to Manila, the marines have no contact with the outside world during their three-month tour of duty. Further confusing life, their island changes shape almost daily.

There is a bit more civilization on the largest island in Freedomland occupied by the Philippines. The Filipinos call it Pagasa, the Tagalog word for “hope,” and it is the only island equipped with an airstrip, which at 12,000 feet is actually longer than the original island.

The occupation force on Pagasa spends most of its time either shelling and making handicrafts or fishing for their lunch and dinner, and growing papayas, coconuts and vegetables in backyard gardens.

No beer is allowed on the island, though the soldiers drink rum on rare special occasions. For diversion, there is a crude basketball and volleyball court, a World War II vintage Ping-Pong table, a battered dart board and a Scrabble game minus most of its letter tiles.

Lt. Panganiban, who is in the first two weeks of his three-month assignment in Freedomland, said his first thought when he received his orders was, “What did I do wrong?”

Thinking of Family

“On my first night here, I was not able to sleep,” he said, as he led his visitors on a one-hour tour that covered almost every inch of his island. “I am thinking all night about my family, my wife and three kids in Cavite,” near Manila, hundreds of miles away.

But the lieutenant said there are advantages to the duty. He and his men receive hazardous duty pay, which adds 700 pesos (about $35) a month to their meager monthly salaries of about $200. It builds close personal bonds--”We are treating each other here like we are brothers, just like a family,” he said. And it is a good time for contemplation, to relax and fish and watch the stars at night.

“It is like Henry David Thoreau’s Walden Pond,” said Capt. Tolin, back on Palawan. “It is place for meditation. The only difference is, they have a very, very big pond.”

Tolin and the other commanders stationed at naval headquarters in Palawan do attempt to make the duty as pleasant as possible. The navy has provided the naval station at Pagasa with a video-cassette machine powered by a generator that supplies five hours of electricity daily. A tiny chapel was constructed in January for soldiers who, like the nation they serve, are largely Roman Catholic. And every Christmas, Navy pilot Lt. Arcenio Obille, who is known by the men as the Flying Santa Claus, buzzes each of the eight Philippine-occupied islands in his twin-engine Islander plane and drops cases of presents by parachute.

“When I see these islands from the air, I can only imagine the courage it takes for a man to live for three months on a tiny clump of sand in the middle of the ocean,” Obille said.

Although all of the men interviewed in the Freedomland occupation force said they believed they were doing something important for their country, they were equally unanimous in their dislike of the duty.

“We are, in a way, forced to like it,” Panganiban said.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.