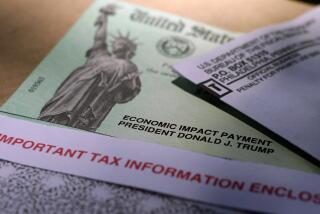

$1.2 Billion in Uncashed U.S. Checks : Bottom Drawers Hold Private Treasury

- Share via

WASHINGTON — On April 15, 1919, the year after the end of World War I, the government issued a check for $1.01 to pay interest on a Liberty Bond.

There was nothing unusual in the transaction except that the check was not cashed until last year, 67 years after it was issued.

The money went to a woman in Nebraska. A Texas couple wasn’t quite as tardy. They only waited 31 years to cash a tax refund check for the princely sum of 10 cents.

A Michigan man gave Uncle Sam interest-free use of a lot more money, $8,606, issued to him in a check dated April 9, 1954, but also not cashed until last year.

In all, 361 Americans received $32,221.40 last year for checks that were more than 30 years old.

Uncle Sam’s bookkeepers say there are nearly 5.5 million checks outstanding that are at least a year old. More than half these checks are in excess of 10 years old.

Add them all up and they represent nearly $1.2 billion lying forgotten in desk drawers.

William E. Douglas, commissioner of the Financial Management Service, the Treasury Department agency that processes government checks, says the current payment system is playing havoc with the government’s efforts to balance its books and keep track of the 650 million new checks it issues every year. The $1-trillion annual payment system has to be designed to accommodate the tiny percentage of checks that are not cashed on time.

“Right now the government has to keep its books open forever,” Douglas said in a recent interview. “Why should the whole process for 650 million checks get wrenched around because a tiny number of people don’t get around to cashing their checks? It’s absurd.”

Douglas is proposing that the government adopt a similar procedure to private business and place a six-month limit on the time that a government check is negotiable.

If held for longer than that, the check would no longer be valid. It would mean that people who were late would have to go back to the agency that issued the check and request a replacement.

While it would be a substantial change from the current unlimited check-cashing window, the revised system, Douglas said, would not work a hardship on most people.

“If it was established that a government check was good for only six months, then people would be more prompt in cashing them,” he said.

The Treasury Department’s legislative proposal also would place a one-year limit on the time the government can go back to a bank and recover improper payments. This process, called reclamation, recovers between $30 million and $35 million for Uncle Sam each year, mainly from errors in recording the face amount of the check. aCurrently, banks are liable to the government for overpayments for six years.

The legislation has the support of the American Bankers Assn., but Douglas said it faces an uncertain future in Congress, where more pressing concerns may keep it from getting a hearing.

But he said he will lobby for the proposal because of the problems encountered in reconciling extremely old checks.

If the check was issued after 1955, the verification can be done by matching computer tapes that reconcile the amount on the check with what was paid out.

But if the check was issued before 1956, then reconciliation is much more difficult because it must be done by manually searching through paper records.

The search is necessary to make sure that no replacement check was ever issued to satisfy the claim. Without verification, the government could pay out twice.

This record search is time-consuming and costs the government on average $19.23 for each old check, Douglas said. He estimated that 155,000 checks of the pre-1956 vintage are still lying around.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.