Sky Is the Limit for Whiz Kid Immigrant

- Share via

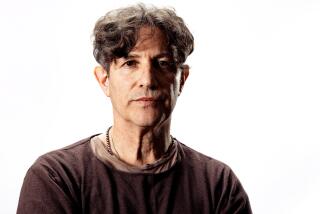

The inquisitive mind of Eli Glezer is the subject of an affectionate family legend.

As a child growing up in Moscow, Eli and his brother Jacob would leave the city each summer and travel south into the Ukraine. There, they would pass their summers with their grandparents in the port of Odessa on the Black Sea.

One day, the story goes, Eli was drawing on the ground with chalk. He drew a figure, its head cocked in a quizzical pose. Why is his head cocked, his grandmother asked the small boy. To which Eli is said to have answered, “He’s asking, ‘Why?’ or ‘Really?’ ”

Eli Glezer is 18 now. He lives on Mango Drive in San Diego, no small distance from Moscow. This spring he is wrapping up one eventful chapter of a rather extraordinary life and preparing to move on to the next. So far, his curiosity has served him well.

Glezer is believed to be one of the top 20 high school physics students in the country. In chemistry, he has ranked No. 1 in the county. In math, he tested in the country’s top few hundred out of the nearly 400,000 that took the high school mathematics exam.

This spring, he was accepted for admission at Caltech, MIT, Stanford and UC Berkeley, an embarrassment of riches that created a difficult choice--a choice subsequently made easier by Berkeley’s decision to throw in a full, four-year scholarship.

What will Eli Glezer become, an old math adviser was asked recently.

“Whatever he wants,” says the adviser, a son of a math teacher

and a math teacher himself who has seen students come and students go for half a century. “That’s it. It’s like the elephant: He sits where he wants.”

Indeed, it has been a felicitous spring.

Late last month, Glezer won a place on the team for the International Physics Olympiad in Germany this summer--20 students selected from 2,500 high schools nationwide. After two weeks of training in Maryland, with the help of several Nobel laureates, five will be chosen to go.

Meanwhile, as a University City High School senior, Glezer was polishing off most of the undergraduate math curriculum at UC San Diego. Having taken no biology in high school, he took it at UCSD and got an A. He also took some physics at UCSD--thermodynamics, optics, wave theory, that sort of thing.

Scholarships, Awards

Then there was the scholarship to Berkeley and a National Merit Scholarship and the top award of the California Scholarship Federation (the last necessitating the tortuous punishment of having to stand before a gymnasium full of people and have his innumerable accomplishments invoked in a well-intentioned, but embarrassing, tribute).

“What do you do ?” Glezer exclaims, telling the story later, with a mix of bemusement and frustration. “You stand there and he’s reading about you! You can’t just laugh . . . and say, ‘Aww, no. He’s just kidding.’ ”

A few adventures in the young life of Eli Glezer:

- In 1980, he emigrated from the Soviet Union with his brother, their parents and four grandparents. The move was abrupt, like the post card that arrived one day, advising them that their request to leave had been granted and that they should go pick up their visas.

The grandparents consisted of two doctors, an engineer and an economist. The parents, a gas-turbine engineer and a chemist. They were leaving to get away from anti-Semitism and to find new opportunities, not least of all for the children.

Books, Slides Never Made It

The Glezers sent a few belongings ahead--books, for the most part, that were lost en route. Barred from sending personal slides out of the country, they slipped a few into boxes of commercially packaged slides. These, too, never completed the journey.

Eleven-year-old Eli was advised not to write to his best friend. It would be dangerous for the boy’s family to be known to have received mail from the United States. He wrote once during the stopover in Europe, but communication stopped there.

But among the crazy jumble of questions put to him over the past year in interviews for colleges and scholarships and other things, came a question that went something like: “If you could meet anyone you wanted, who would it be?”

His answer was Albert Einstein and the Russian friend.

- The family touched down in Los Angeles that April. Eli’s mother, the chemist, took a dental hygiene course and briefly went to work cleaning teeth. His father, the engineer, was hired by a large turbine-engine firm in San Diego, where the family eventually moved.

Eli, meanwhile, found himself in the waning days of an all-American fifth grade in a Culver City elementary school. As he tells it, he knew the English words for yes, no, knife, fork and little else.

Suddenly, report cards were being handed out. “I could care less about my grades; I was just trying to understand what was going on,” he remembers. But a friend checked out Eli’s report card and swooned, “Whoa! That’s sooo good!”

“I guess they probably treated me nicely,” suggests Glezer, never one to overstate his case.

- Three years later, living in San Diego, Eli entered a state science fair. His project was a high-temperature solar heater and water desalter. Two components consisted of plexiglass lenses forged in the family oven using the family wok.

“I got a couple of drops of fresh water,” he says with a shrug--for which he won first place among all of California’s seventh and eighth graders. The following year, the competition was stiffer in the ninth- to 12th-grade category. He came in second.

- During his sophomore year in high school, Eli learned of a large San Diego defense contractor doing work in fields in which he was interested. He put together a resume, stopped by, had some interviews. He was too young for security clearance.

The following summer, the firm hired him to work in a branch not requiring clearance. He spent the summer as a computer programmer--a skill he had absorbed on his family’s computer, and sitting in on two courses his parents had once taken at UCSD.

John Turley, the math adviser, is ensconced in a capacious arm chair in his house in University City. Retired from full-time teaching, he is ruminating with apparent pleasure on what he calls “one of my most enthusiastic subjects.”

By memory, he rattles off Eli Glezer’s rather memorable scores on the Mathematics Assn. of America’s high school exam over the past five years. Then he traces the leaps and bounds of Glezer’s mathematics education.

“He was in ninth grade math in eighth grade, then he took 10th-grade math in ninth grade. Then he decided to skip the pre-calculus course--the junior-level course. That summer, he took the book and he came to me for about three tutorials.

“There were very few things he didn’t understand. He just went through that and he scored among the highest in the city on the calculus qualifying test. So he was in calculus as a sophomore, which is something that happens, oh, I’d say maybe once in 30,000.”

How does one explain it, Turley was asked.

“You might take the steps that you go through in working mathematical problems: A person who is not skilled at all takes a long time to get through step one, two and three. It’s labor. Now, Eli takes step one--and immediately goes to step four.”

Of course, Glezer will tell you there are things that don’t come easily.

Surfing, for example.

“Surfing’s a hard sport,” he volunteers. “To get real good.”

He ran on the cross-country team in 10th grade; he figures that’s something he could never do very well. He plays the piano well but insists he has no ear. (An early piano teacher told his mother he did it all with his mind.)

Biology class at UCSD was no piece of cake. He was sure he’d get a B (his first), but ended up with an A. “Return of the Native” in English class seemed a tedious chore. Then there was that class last year, which shall remain discreetly unnamed.

“The reason I found it difficult was I’d always fall asleep,” he says. “I’d start reading that book and I’d fall asleep. . . . And our teacher, he’s probably the only man I know who can stand in front of a classroom and move only, only , his lower jaw, for an hour.”

Five and a half years ago, Eli and his brother began studying karate. They began because of a friend, whose father was a UCSD dean who had known a student skilled in martial arts. The former student began instructing the boys. Gradually, the training took on increasing significance.

It moved beyond self-defense to the philosophy of martial arts--the importance of such things as discipline, respect, perseverance and humility. As Eli has put it, the atmosphere is one of cooperation, not competition. The class is a place to break through self-imposed limits.

“Gichin Funakoshi, the man responsible for taking karate to Japan from Okinawa, said, ‘The real goal and purpose of karate is the perfection of character,’ ” Eli once wrote. Which is one reason why, he said, he studies karate.

One college asked applicants to elaborate on a favored quotation. Eli chose a quotation from Bodhidharma, the 6th-Century Indian monk who founded Zen Buddhism: “To fall seven times, to rise eight times--Life starts now.”

“It’s got two parts,” he said recently. “First, the idea of falling, that it’s OK to fall once in a while because only then can you appreciate success. . . . And life starts now. No need to be so concerned about the past or the future that you forget what you’re doing now. Enjoy what you’re doing now. Concentrate on that.”

Glezer always has been interested in the way things work. He read books in Russian as a child that surfaced this year on high school course lists. He remembers conversations with his father at a young age about why airplanes fly and how engines run.

Take the question, “Why is a sunset red?” Of course, it’s possible to appreciate beauty without having to take it apart, he says. But once you understand the reasons behind something, he suggests, isn’t there “a different kind of beauty?”

One of the attractions of Caltech was the presence of Richard Feynman, the Nobel Prize-winning theoretical physicist--a man known also as a humorous, incisive free thinker with an inquisitiveness that never stops.

‘Ideal Creative Scientist’

“He seems like the ideal creative scientist, and also one who’s willing to try just about anything,” muses Glezer. “. . . I think after you do physics and things like that, after you deal with things around you, after a while you get a kind of understanding of things. I think someone like that--he’s got it.”

Asked to describe that understanding, he continues.

“Sometimes you look at a problem and you’ve never seen anything like it before. But you just kind of know how to approach it . . . Say, atomic structure, quantum mechanics--things that we have no common experience in, things that we have no physical connection with. The only way we can understand them is through analogies, analogies to our physical world. I think if you have the right set of analogies and you see things the right way, then you really understand something.”

What will he do?

He figures he may do a double or perhaps triple major--a combination of things like mechanical engineering, physics and nuclear engineering. “Not because I want to kill myself,” he points out, but because he already has so many credits from advanced placement courses and classes at UCSD that he could graduate in 2 1/2 years.

“If I have a four-year scholarship, you know, why not?” he asks.

Beyond that, he’s interested in private industry or academic research; right now, research seems the more challenging of the two. He’s interested in aerospace, in part because developments are occurring rapidly there, and in high-energy physics, such as fusion.

Or the big bang.

“I read a real interesting book on that,” he says.

“It seems like it really challenges the mind--how out of nothing there can be something. A lot of other things, things like evolution, aren’t as hard to understand, because you have something and it evolves into something else. For me, (that’s) easier to grasp.

”. . . You go back further. Did it start off with something? Did it start off with nothing? The book talked about how everything in the world tends to go to randomness, right?. . . As you go back, it becomes more and more ordered. And what’s the most orderly thing you can think of? Nothing. So somewhere in there, something in nothing got out of symmetry.”

He laughs.

“That’s a pretty wild theory.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.