Biking the Bends of Danube in Austria, Hungary

- Share via

BUDAPEST, Hungary — “Not blue at all,” she said, as we wheeled along the levee, the Danube on our left.

“I would call it gray-green, but still impressive.”

Earlier that morning my wife, Catherine, and I had left Linz (the city that gave the world the Linzertorte and a Mozart symphony) on a two-week jaunt down this mighty river through Austria and Hungary on two high-tech multispeed bikes.

Destination: Budapest. Mission: Savor an adventure under our own steam alongside this mighty waterway.

The clever Austrians had built banks of earth along most of this river plain to contain periodic flooding, and on the top had laid macadam paths for cyclists and walkers. These lanes are called treppelweg (towpath), on which at one time plodding horses dragged a barge. Now they provide magnificent views of both the river and the vast alluvial landscape of meadows, farms and woods.

As we rolled past the rich vegetation and wildflowers in the July sun, our sole companions for miles were the swans drifting along the water, the paddle-wheel steamer leisurely navigating the current, an occasional knot of children skipping along the path, or strolling lovers.

In Lovely Linz

The day before, we had boarded the Trans-Alpin Express in Basel with bicycles safely deposited in the baggage car (for a small fee), and arrived as daylight waned in lovely Linz to find a gasthaus and good food at a restaurant.

The first leg of the journey crossed the river to the north bank and turned east. Towns such as Mauthausen, Grein, Krems, Melk and Tullin are all conveniently within a day’s biking distance of each other, 35 to 45 miles.

The day had been spent crisscrossing the river as we sought the treppelweg, thus bypassing main truck-bearing roads. A grim reminder of the Nazi past came up in Mauthausen, where a concentration camp had operated in the quarries near the center of town. People understandably were reluctant to point out the direction to this relapse into barbarism. The village exhibited all the serene charm of rural Austria.

Our favorite was Grein, a cobblestone village with an ornate well in the town square, pastel houses and flowers festooning every window.

Arriving in late afternoon and downing a beer at a cafe, we were seduced by its picturesque scene and in no mood to push the pedals another 10 or so miles to the next stop, so we settled in at the convenient Pension Martha, where a comfortable and spotless room with bath cost 340 schillings ($25 U.S.).

Comfortable Inns

Our manner of two-wheel travel does not envision sleeping on the ground under the stars or in a tent when it rains. Sleeping and cooking gear do not weigh down our panniers (saddlebags on front and back of the bicycles). We seek out comfortable inns, guest houses and even two- or three-star splurges for layovers of a day or two.

Nor is our pace comparable to the Tour de France (Europe’s marathon bike race). We leisurely poke into this village or that and regularly break for coffee and pastry at the ubiquitous cafes or pubs.

In the next few days our thin bike wheels negotiated a varied terrain of treppelweg, Alpine lanes in the Wachau district near Krems, and ordinary farm roads approaching Tullin. In Melk, at an immense monastery on a brow overlooking the Danube, we glimpsed the splendors of the Austrian baroque style. Drab yellow masonry outside signals no warning of the riot of red and cream Italian marble, religious paintings and gilded columns inside.

In Touch With Nature

After this visual orgy, we felt more in touch with nature in the wine-growing Wachau, often compared to the Rhine with its castles. Treppelweg gave way to back roads, leafy steep banks and terraced vineyards. Straw wheels festooned with ribbons were on display at rustic huts along the way to announce that new wine was ready.

“What sort of wine are you serving?” I asked a white-garbed saleswoman at one of these shops in Rossatz. Instead of answering, she gave us pearly glasses of wine, a very dry white. It cost about 40 cents and was wonderfully refreshing, but one must be careful not to have too much while pedaling. Wine at dinner was another matter.

Food becomes an obsession of a touring biker who burns up more than 300 calories an hour.

Fortunately, Austrian cuisine, a cross between German and Italian, can satisfy the lustiest of appetites. We generally like to picnic for lunch, and every village sold sourdough black bread, cheese, salami (our lunch, for example, in Mauthausen) which we could take to a cafe and wash down with a brew.

Stepped Up Intake

At night we stepped up our intake in restaurants, sampling specialties such as fogash (fish from Lake Balaton in Hungary), served in our inn at Hainburg, and finishing up with palacinka smothered in elderberries.

Sometimes the fare was strictly Teutonic, as at the Gugl Vert in Krems, in which plates heaped with goulash and pork dumplings, peasant style, mit sauerkraut, complemented a stein. In spite of robust meals, we ended up thinner than when we started because of all the outdoor exercise.

Those lovely steamers going up and down the river reminded us of Mark Tawin’s Mississippi paddle-boats.

Catherine came up with the idea: Why not enter Vienna via the steamer rather than by the usual traffic-clogged and malodorous route into a large city?

Luck! Bustling Tullin had a Schiff Station, we discovered as we wheeled into town, and right on the treppelweg, too. Dinner and strudel could also be had there. In two hours from boarding the boat we would be in the heart of Vienna.

Vienna’s charms are best discovered on foot. In mid-July the city roasts, empties of burghers and is invaded by tour buses.

After days of luncheons and snacks at Demel and the Cafe Aida, and gaping at paint and marble at the Kunstmuseum, the Kunstlerhaus, the Hofburg, and nights of heavy dinners at Grinzing or strolling the Ringstrasse, two cyclists might be forgiven a yearning for the open road and the treppelweg.

The line-up of tourists waiting for visas at the Hungarian Embassy at 8 a.m. Monday could have discouraged the hardiest of Eastern European admirers.

“The queue moves fast once the doors open,” said an Israeli in front. In 90 minutes we had the documents which would allow us to pierce the Iron Curtain.

Wide Expanse of Water

By 10 we were gliding through Vienna’s eastern suburbs in search of the road paralleling the Danube, which had become a wider expanse of water with each passing kilometer.

This segment of the river flows through the Marchfield, a rich agricultural plain, bucolic scenes of meadows, ruminating cattle, fields of hay and grain and modest farm dwellings.

One would hardly guess that a great battle with immense casualties was fought here near the village of Wagram, where Napoleon’s 150,000 troops won decisively against the Austrian army in 1809. A street in Paris is named after it, too.

We soon nosed out the treppelweg, but the royal road to romance had metamorphosed into an unpaved path. Although rough on the tires, it was still passable and enjoyable. The pebbly track, isolated from house, village or human presence, took us by late afternoon within eyeshot of welcome Hainburg. A town of pastels and flower pots, it cherishes its medieval walls and the memory of Haydn who studied here as a musician.

Only a few miles from the Hungarian border, I causally asked the owner-host at the Goldenen Krone, a picturesque old coaching inn where we stayed the night, what the border crossing was like. In halting English, he said he had never been there. “Never crossed into Hungary?” I asked, surprised.

“Why should I go to that horrible place?” he remarked candidly.

With Heavy Hearts

Although apprehensive, we were determined, and after a morning’s dash over the flat countryside, we approached the heavily guarded border with heavy hearts. The checkpoints on the Austrian line were almost deserted, but when we wheeled onto the Hungarian side, we began to appreciate the term iron , for iron was everywhere: machine guns, pistols, rifles, gates, towers, and looks.

There were three checkpoints for showing passports and visas on the grim passage into the other world. No one bothered to peer into our panniers. No one spoke English, and even German seemed beyond the guards.

“Do you think it’s wise to trundle through Hungary’s hinterland without a word of their language and very little German?” Catherine asked.

“Maybe they have high school French” I said.

We headed for lunch into Mosonmagyarovar, just over the border. As others before us have noted, the glories of Hungarian cuisine survive in Soho of London or the Upper East Side of New York. But they have not survived at the Elephant restaurant in Mosonmagyarovar.

Other people were eating fish and chips, which is what we settled for--and a lemon drink made from concentrate. A sign language of pointing, charades and shakes of the head was all we had to communicate with the waiter.

A Different Reality

Our destination for the evening was Gyor, which seemed like a large city. It boasted a four-star hotel, but like everything else on paper in Hungary, reality differs appreciably. The back roads were as good as any in France and the smooth macadam stretched through many a village that few foreigners ever see.

In one of these settlements, Darnozseli, we stopped at what passed for a pub to moisten our throats and escape the heat. A beefy red-faced man who communicated with us in German announced with awe that we were American. Hardly anyone stirred or seemed interested. What a difference from bike travel in Austria or Italy, where our arrival brought out half the inhabitants of small towns.

The four-star hotel Raba in Gyor was a rambling half-old, half-new building with uncertain plumbing and comfortable beds, but for 1,300 forints ($26 U.S.), no complaints. With the menu in Hungarian, we ordered wine and got a bottle of sherry. The beer, Gold Fassel, was excellent.

The six-man orchestra--every large restaurant offers live music in this part of the world--rendered ‘30s tunes like high-school bands of the ‘40s and ‘50s. But the cafe down the street served late-night coffee and doboschtorte as good as Vienna’s Konditorei.

A Secret Love

Breakfast the next morning in the hotel dining room surprised us with very garlicky sausage and bread, but if you have a secret love of Hungarian salami (one of the best in the world), this is pig heaven. Four things in the land of the Magyars--to accentuate the positive--seemed praiseworthy: coffee and pastry, draft beer and salami.

Out on the open road after such a heavy morning meal, at first we crawled along the Danube on the way to Komaron and the scenic Danube Bend, where there is a summer resort.

The vast fields soon gave way to woods, hills and leafy prospects as we wheeled off the fatty breakfast and fried lunches for the next few days on our way to the Hungarian capital. Cafes with charm multiplied, hotels spruced up, and next to one, the Furad, in Esztergom across from Czechoslovakia, a huge municipal swimming pool brought us relief from the late afternoon heat.

On the final leg of our trip, we took a ferry and bridge to and from Szentendre Island, 20 miles of fertile land dividing the river. A combination of truck farms and vacation villas were our scenery as we slowly edged down the island and coast.

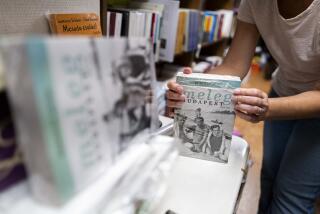

The most charming town of all is Szentendre, 12 miles from Budapest, rich in 18th-Century baroque houses in colorful pastels and full of art galleries and milling crowds.

In two hours, our bikes rolled by Margitsziget (Margaret Island) in the heart of Budapest, and we searched for the bridge to take us over to Pest (the east side) and the Hotel Royal in the busy Lenin Korut of the shopping district.

After three days of rest and recuperation in this vast city, we realized that our fears of travel behind this silly Iron Curtain were exaggerated, and except for an occasional inconvenience, the language barrier did not prevent us from enjoying our bike tour.

We would return via the Orient Express to Paris (our bicycles sent along for a pittance and ready for us on arrival at the train station). We recounted to friends an adventure of a wonderful waltz along a waterway that everyone has heard of but few have traced.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.