Quimmley’s Gone, But Not Forgotten

- Share via

Although Webster Quimmley was given a decent burial in Dixon Gayer’s garage more than 20 years ago, he is still disinterred periodically to do his thing. Just the other day, Gayer got a letter from a northern California man who inquired about Quimmley’s whereabouts and remarked admiringly that he could still command a large following if he chose to reappear.

That isn’t likely. Gayer would prefer not to disturb Quimmley again, although he did dig him up for this visitor in a dusty cardboard coffin where Quimmley’s corpus is wrapped in a shroud of clippings, badges and bumper stickers.

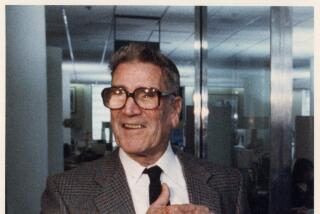

Right on top is a yellowed picture of Gayer laughing from a page of the Los Angeles Mirror. He’s fondling a professorial pipe and tipped back in his office chair at Long Beach State College, clearly enjoying the knowledge that the adjacent headline is going to pair him with the embattled Webster Quimmley, who captivated first Orange County, then the whole nation back in the early 1960s.

Quimmley was Gayer’s mythical alter ego, a joke that refused to die peacefully because it appealed to so many politicaly confused Americans.

Gayer was a professor of journalism at Long Beach State in the early ‘60s, and was also moonlighting as a columnist for the Garden Grove News. Those were the days when the John Birch Society went galloping out of Orange County, convincing a fair number of citizens in its wake that they should stomp anything and anyone whose views didn’t coincide directly with those of the Society.

Gayer’s didn’t, and he said so, and he was stomped. He found that funny at first, then irritating, so he raised his own decibel level to try and apply logic to arguments that were inherently illogical. It didn’t work, of course, and Gayer was growing increasingly frustrated when he received a letter from a woman reader who told him to bring up his best weapon: humor. Thus Webster Quimmley was born.

Gayer told Quimmley’s pathetic story in his column the following week. Webster Quimmley was a Midwestern transplant to Orange County. He avoided the freeways in his Essex touring car, but one day he had to go to Los Angeles, and so ventured onto the Santa Ana Freeway. He carefully established himself in the middle lane, then became increasingly frightened as drivers careened by him on both the right and left, cutting him out and shouting epithets at him as they passed. The speed and recklessness of the drivers on both sides of him were so excessive that Quimmley couldn’t get off the freeway. So, finally, he simply stopped in the middle of the freeway, stood up in his car, and shouted: “Sanity and Freedom.”

The police led Quimmley off the freeway and told him to take surface streets the rest of the way. When Quimmley returned from Los Angeles--shaken but still defiant--he moved back to the Midwest. But his legacy lived on, and in his memory, Gayer suggested founding the Webster Quimmley Society for people who preferred the middle road to the excesses of either right or left.

Gayer’s editor thoughtfully put the story on the Associated Press wire, and it exploded all over the country. “All of a sudden,” recalls Gayer, still a little awed, “the story began popping up with datelines from a dozen different cities. I knew there couldn’t be very many people on either extremity, but they were making all the noise. We needed a voice for the 150 million people in the middle, and I had no idea how hungry they were for it. “Within a month, I had almost 10,000 letters from people who wanted to join.”

He could have tried to kill off Quimmley by ignoring the deluge, or exploited him by charging a fat membership fee and then going into the Webster Quimmley T-shirt business. He did neither.

Instead, he hired a couple of students to make plywood membership badges (birch on top, redwood on the bottom, with “good American oak in between”), designed a membership card that inside carried an “Instant Disclaimer” (“I’m not a member of either the Communist Party or the John Birch Society”), and asked a modest $1 membership fee.

It wasn’t nearly enough. Gayer didn’t keep track, but he estimates he lost thousands of dollars trying to satisfy the requests of Quimmley’s friends. “It went on for a couple of years,” says Gayer. “Every time I thought Webster was buried, he’d pop up again.”

Although the college predictably got a lot of hate mail, it stood behind Gayer. But new owners at his newspaper found him too hot to handle, and he lost his column. So he started a paper of his own called The Dixon Line that published for 11 years as one of the few distinctly liberal voices in Orange County.

“It’s funny,” muses Gayer, “but I never saw myself as all that liberal. I was a moderate Stevenson Democrat. That’s what I was trying to point out through Webster: when extremists of any persuasion get in their ditches and start to throw rocks, they aim at everybody who isn’t in there with them.”

Gayer was still teaching and publishing when his doctor discovered a heart irregularity serious enough to hospitalize him for several weeks. When he got out, he hung it up. The last issue of The Dixon Line was published in 1975, and several years later, he retired from Long Beach State.

To do what?

“Well,” he answered, “Fred Allen used to tell a joke about a man who told his wife he wanted a divorce. When she asked him why, he said: ‘To get on with my goddam life.’ That’s what I’m doing: getting on with my life.”

At least on the surface, Gayer has changed surprisingly little since creating Quimmley. He is almost 70 now, and there are some wrinkles and a bit of a belly, and the tweed jacket and natty slacks have turned into jeans and a cotton shirt. But the the eyes are still very much the same. Bemused. Irreverent. A little wary. But mostly looking at the absurdities with which we cope daily and finding them pretty funny.

Gayer lives--as he has for the past two decades--in a Huntington Beach home full of Oriental art with his wife, Lorraine, two Silky terriers, several dozen koi fish, a macaw and two parrots. And a spectacularly cluttered office.

Does Gayer think Webster Quimmley would catch on in the more sophisticated environment of Orange County today?

“Sure he would. I don’t see all that much change here. But I do see hope--and I didn’t see much of that before. Not in the Yuppies who have moved here in droves but in the general population growth, especially workers who have made this more of a blue-collar community. That’s where the hope is.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

![Vista, California-Apri 2, 2025-Hours after undergoing dental surgery a 9-year-old girl was found unresponsive in her home, officials are investigating what caused her death. On March 18, Silvanna Moreno was placed under anesthesia for a dental surgery at Dreamtime Dentistry, a dental facility that "strive[s] to be the premier office for sedation dentistry in Vitsa, CA. (Google Maps)](https://ca-times.brightspotcdn.com/dims4/default/07a58b2/2147483647/strip/true/crop/2016x1344+29+0/resize/840x560!/quality/75/?url=https%3A%2F%2Fcalifornia-times-brightspot.s3.amazonaws.com%2F78%2Ffd%2F9bbf9b62489fa209f9c67df2e472%2Fla-me-dreamtime-dentist-01.jpg)