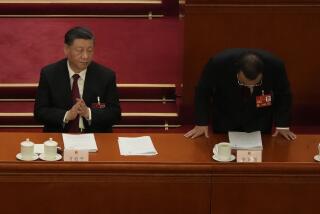

Time Runs Out for Traditionalists in China

- Share via

If Soviet leader Mikhail S. Gorbachev isn’t too busy with his own problems these days, he may well be studying what just happened across the border in China.

The Chinese are several years ahead of Gorbachev in the process of trying to bring about economic reforms under communist leadership. The more time goes on, the more it seems that such reform efforts inevitably create serious, perhaps irreconcilable factions and divisions within a Communist Party leadership.

The significance of the past two week’s political developments in China does not lie in the supposed retirement of Deng Xiao-ping or in the announcement that Premier Zhao Ziyang would take over as head of the Chinese Communist Party. The reality of Chinese politics is such that Deng would still be the leader of the nation even if his only official title were vice director of the Chinese Spitoon Users Friendship Assn. Deng has been claiming to “retire” from Chinese politics for several years and has ruled China while holding several different posts. That is, after all, why he is usually referred to simply as “the paramount leader,” a title he cannot and does not give up.

Rather, the Communist Party Congress that just ended in Beijing is a milestone because of the abrupt ouster from the leadership of those traditionalist leaders who had been campaigning against Western influences in China. Their fall from power represents an end to Deng’s prolonged effort, dating back to the beginning of this decade, to balance carefully the often-conflicting reform and conservative wings of the Communist Party. It is a risky strategy, one that could well speed up the pace of change in China but, conceivably,could also lead to an abrupt political turnaround after Deng’s death.

China’s traditionalists were part of the coalition that supported Deng’s rise to power in the late 1970s, after the death of Mao Tse-tung. Like Deng, they had been cast aside during the Cultural Revolution and had been bitter enemies of the radical leftists led by Mao’s wife, Jiang Qing. But throughout the ‘80s, as Deng launched his reform program and brought along new, younger leaders to take charge of the reforms, the traditionalists began to warn of what they viewed as deleterious ideological and cultural side-effects to these economic changes.

These traditionalists argued that it might be all right to open up the way for such changes as wage incentives, market prices and a small degree of private enterprise--but not if it meant that China’s 1 billion people would come to view the accumulation of money as the ultimate goal in life. It might be all right for China to import some Western technology, they said--but not if doing so gave the masses the feeling that China was inferior to the West. It might be all right to reassure Western capitalist nations and borrow their management methods--but not at the expense of disavowing the ultimate ideal of creating a communist society.

The people voicing such views were not lower-level officials. They included men such as Hu Qiaomu, the Politburo’s leading expert on ideological matters; Deng Liqun, who served as party propaganda chief from 1982 to 1985, and Peng Zhen, the head of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, China’s legislature. These men spearheaded the short-lived but intense campaign against “spiritual pollution” in 1983, which led to local officials banning Western fashions and even haircuts for young Chinese. Last winter, once again, these men were in the forefront of the regime’s drive against “bourgeois liberalization” following a series of student demonstrations and the resignation of the reform-minded Communist Party secretary, Hu Yaobang.

But Deng is one of the wiliest political operators in the world. In ruling China, his approach has usually been to compromise with political rivals. Since the early ‘80s, he had repeatedly allowed the traditionalists to keep a foothold within the highest ranks of the Communist Party. Not this time.

At the party congress just ended, the leaders of the campaigns against “spiritual pollution” and “bourgeois liberalization” found themselves shut out of the party’s new Politburo, Secretariat and Central Committee. The message was that Deng has thrown all his support to the reform wing.

So what are the lessons for Gorbachev? The Soviet leader is a good eight years behind Deng in the process of trying to overhaul his country’s centrally planned economic system. By all appearances, the initiation of perestroika , or restructuring, has begun to divide the Soviet leadership in the same ways as Deng’s reform program did earlier in China. There are those who favor an active, aggressive speeding-up of change, and there are others who seek to ensure that the reforms do not go too fast or lead the party to stray too far from its roots and historic values.

Gorbachev may seek for a time to balance the different schools within the party. But over the long run, he may have to make a choice--as Deng just did.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.