Soviet Director Calls for Cutting the Iron Curtain in Animation

- Share via

“We can’t accept any more of this Iron Curtain between our two animation industries,” says Soviet animation director Fyodor Khitruk. “I’ve been delighted by the way audiences in America have received Russian films, and vice-versa. I feel as if there’s almost been a plot between the U.S. and Soviet bureaucrats to discourage film exchanges, so we’ll have to arrange them ourselves.”

Khitruk, an award-winning director and chairman of the animation film committee of the U.S.S.R. Assn. of Film Makers, arrived in Los Angeles Sunday on a visit sponsored by the American-Soviet Film Initiative. The initiative, established earlier this year after a visit to Hollywood by top Soviet film industry leaders, is a joint U.S.-Soviet organization facilitating communication and cooperation between the two nations’ film makers.

As part of the effort to establish further exchanges of animated films, Khitruk is spending his week meeting with representatives from the Walt Disney, Filmation, Hanna-Barbera, Marvel and Jambre studios, as well as executives from the childrens’ programming divisions of the three major TV networks.

Khitruk also will present a program of Soviet animation in Melnitz Hall at UCLA tonight and speak Friday night at the International Animation Society’s Annie awards banquet honoring outstanding animation professionals.

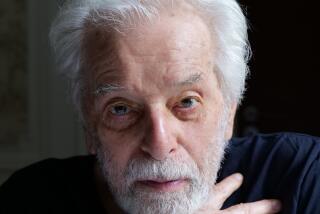

A dignified but friendly man, Khitruk discussed the proposed film exchange and other aspects of his work in an interview at his Universal City hotel room shortly after his arrival. He switched between English and Russian with the help of an interpreter.

“Russian and American audiences are very different,” he said. “The reaction to the program of Soviet films I showed in Minneapolis last week was more enthusiastic than any in the Soviet Union: There, I could only dream of such an audience!

“But when people here see animation, they expect something funny: They wait for the moment when they can laugh. If the film has no real gags, they’ll laugh at anything that resembles one. They’re not used to serious animated films--you’ve trained people to expect jokes. I think Tom and Jerry and Road Runner cartoons are very important, but it’s just as important to have some serious work being done. There should be a balance.”

Of the 24 government-sponsored animation studios in the Soviet Union, Khitruk said, 15 make films for theatrical distribution. The other nine are engaged in television production. Together they release about 130 films each year, 70% of them intended for children. In addition, the Soviets expect to complete animated features based on Rudyard Kipling’s “The Cat Who Walked Alone” and Robert Lewis Stevenson’s “Treasure Island” this year.

Khitruk lamented the poor quality of many children’s films in both countries.

“So much kitsch is produced for children: It determines their taste and becomes a kind of aesthetic imperative,” he said. “The human psyche is actually formed between the ages of 6 months and 5 years. I’m astonished that the artists don’t take any responsibility for the work that’s shown to children: They know it’s part of their education.

“The problem is not restricted to the Western countries. We make many bad films as well. Some should never be made, and some would be OK to make if you didn’t show them. Kitsch can be professionally done or amateurish, but it’s still kitsch.”

Although Soviet films have received awards at the major international festivals, Russian animation is rarely seen in the United States. Soviet animators have often been criticized for a tendency to shy away from taking risks and making bold statements--a situation Khitruk feels is changing.

“In the last 10 years, a new audience comprised of students and professionals has grown up,” he explained. “They have film clubs where they watch serious works because more of these films are being made. The films are beginning to create their own audience.”

Khitruk also said that the Soviet Union’s new policy of glasnost (openness) has removed some restrictions on animation and other types of film making:

“We’re much freer to express our ideas in our films now, even in areas like political satire, where there used to be censorship. We also have a new rule that any foreign film we buy will be shown in its original form--without any changes or reediting. I think it’s important for people to see and judge for themselves, rather than reading in the newspapers about someone or something you’ve never seen.”

In addition to the film exchange, Khitruk will investigate the possibilities of joint U.S.-Soviet animation production:

“Although we haven’t found a partner yet, we have proposals for two films,” he said. “The first would be a satirical look at the stereotypes we have of each others’ cultures; the second is tentatively entitled ‘The Chronicles of One Planet.’ It would explore how life developed on Earth--and how quickly it can be destroyed.

“We’re also interested in projects that would allow us access to some of the state-of-the-art American equipment. We don’t yet have the hardware or software to produce much computer animation.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.