A Century of Russian Jewry : A CENTURY OF AMBIVALENCE : The Jews of Russia and the Soviet Union, 1881 to the Present <i> by Zvi Gitelman (Pantheon: $39.95; 387 pp.) </i>

- Share via

Anyone with even a passing interest in the history of Russian Jewry will want to own this splendid new book by Zvi Gitelman. A comprehensive textual view of the last century’s events, the volume also contains about 400 photographs, some of them both rare and remarkable.

Gitelman begins his inquiry with the assassination of Czar Alexander II, known as the “Czar Liberator,” in 1881, and concludes with some comments and insights concerning the current regime of Mikhail Gorbachev. Yet, as the author himself indicates, the story of modern Russian/Soviet Jewish history has its origins a century earlier, with the Russian annexations of eastern Poland between 1772 and 1795.

Confronted with the acquisition of nearly half a million Jews under their rule, Russian sovereigns confined them to a “Pale of Settlement,” in order to prevent these Christ killers--as they were considered--from moving beyond the areas they already inhabited. During the next century, according to Gitelman, the czars paid more active attention to their Jewish subjects, although this was by no means always a boon to the recipients. Instead, the result was a “cycle of repression and relaxation that was to create and re-create enormous Jewish ambivalence toward their homeland.”

It is easy to see why the collective attitude of the Jews themselves has been one of ambivalence; yet, seen from the outside, their experience is best described as contradictory. As Gitelman’s readable exposition unfolds, a repeated vacillation between acceptance--or at least tolerance--and vilification emerges as the overarching pattern of Russian Jewish life. The result is a history of highs, such as the formation of the Bund (a Jewish socialist organization) in 1897, a year prior to the founding of Lenin’s Russian Social-Democratic Labor Party, and helpless lows, epitomized by Stalin’s ruthless purges of Jewish creative and intellectual giants such as Dovid Bergelson, Peretz Markish, and Shlomo Mikhoels.

Gitelman is careful to point out, however, that what might at first seem to recapitulate an earlier moment may, in fact, be a different moment entirely. Take, for instance, the anti-Judaism campaigns of the 1920s and those of the 1950s and 1960s.

The post-Revolutionary attempts to wean Jews away from orthodoxy, Zionism, and devotion to the Hebrew language were conducted mainly by Jews and expressed through the medium of the Yiddish language. The author interprets this phenomenon as an outcome of Jewish diffidence, as the need to prove that they could “transcend kinship in order to serve ideology.” In sharp contrast, the later efforts, between 1957 and 1964, were disseminated in Russian as well as other languages and allowed for the frank promulgation of anti-Semitic ideas.

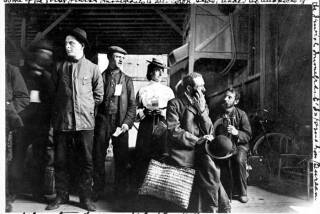

While many of the facts Gitelman provides may be familiar to his audience, even the most sophisticated reader will have much to learn from studying the wealth of unusual, frequently fascinating photographs that are an integral part of the book. Culled from the priceless archives of the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York, as well as from private collections, these photos serve as a vivid reinforcement of the text, even as they extend beyond it in ways that are unexpected and too numerous to catalogue fully.

There are, for instance, pictures of ordinary Jews from the 1880s until the present, representing life in urban areas, in agricultural colonies, in Central Asia, in the Crimea. There are also photos that shed light on well-known figures, including a 1897 family portrait depicting the composer Aaron Copland’s grandparents.

“A Century of Ambivalence” ends with the observation that Jewish identity in the Soviet Union has been maintained, perhaps even strengthened by the constant official attention to it. In the end, this deep and powerful connection to history and community proves to be central.

A poignant example concerns Vladimir Medem, one of the Bund’s founding leaders. The son of baptized Jews, he is quoted by Gitelman reporting his return to Judaism: “When did I clearly and definitively feel myself to be a Jew? I cannot say, but at the beginning of 1901, when I was arrested for clandestine political activity, the police gave me a form to fill in. In the column ‘Nationality,’ I wrote ‘Jew.’ ”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.