May Not Be a Pretty Sight

- Share via

The love-hate relationship between the United States and the Philippines, its former colonial possession, will again go on display this week as negotiations open in Manila on the future of the major American military facilities at Clark Air Base and Subic Bay Naval Base. Like most squabbles between people who know each other too well, this may not be a pretty sight.

Technically, the talks involve only how much compensation will be paid during the final three years of the current agreement on the bases. But the talks may also provide clues about whether President Corazon Aquino will yield to the nationalist sentiments that are being increasingly voiced in her country and demand an end to the 90-year-old U.S. military presence when the agreement expires in 1991.

More than any other single issue, the bases wound the pride of Filipino nationalists, reminding them of their continuing economic dependence on the United States and of their former dependent status. Aquino has appointed several outspoken critics of the bases to high office, among them Foreign Affairs Secretary Raul Manglapus, who heads the Philippine negotiating team. Aquino, on her own part, has said she is keeping her options on the bases open.

So critical are the bases to U.S. military strategy and to the Philippines’ economy that American diplomats as well as many Filipinos assume the agreement governing their use will be extended, no matter how fiery the rhetoric becomes. Especially since the fall of Vietnam, it has been important to Pentagon planners that Clark and Subic, the largest American bases outside the United States and the center of operations reaching from the North Pacific to the Indian Ocean, remain part of the U.S. defense network. Relocating those facilities hundreds or thousands of miles to the east would cost billions of dollars. Moreover, the bases are integral to the Philippine economy. Together they employ 68,000 Filipinos and produce hundreds of millions of dollars each year in off-base expenditures.

Manglapus, who once said the bases negotiations could be a tool “to slay the American father-figure image,” has hinted that he will demand U.S. compensation in excess of $1 billion spread over the next three years; the United States now pays about $180 million a year. The $1-billion figure, apparently plucked from the air, seems clearly unrealistic given U.S. budgetary restraints and Congress’ reluctance to contribute more to the Philippines troubled economy.

That reluctance has been bolstered by evidence that Aquino’s government is still not adequately prepared to deal with the enormous economic inequities that burden the Philippines. More than $1 billion in international economic aid to Manila remains unspent, in good part because of bureacratic inefficiency and administrative ineptitude.

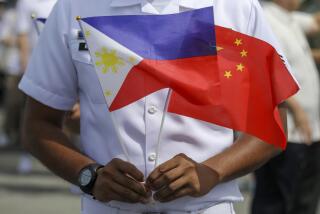

Aquino’s government, of course, doesn’t like to hear about its managerial shortcomings, any more than the United States enjoys hearing claims from Filipinos that the Clark and Subic bases serve only American interests. Plainly the bases are of major military importance to the United States. But not to the United States alone. Other Asian nations, China among them, have not been shy in suggesting that regional security would suffer if the bases were shut down. There’s no way to tell how much weight this view may carry with the Aquino government. In the end, what will be decisive is whether Manila concludes that the U.S. military presence and the political relationship it symbolizes serve the Philippines’ interests. Eventually that is the conclusion that probably will be reached in Manila. Meantime, though, the long U.S.-Philippines alliance almost certainly will be subject to new stresses.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.