Telesis Officials Call Flexibility Key to Future : New Chief, President to Push for Reforms on Pricing, Services

- Share via

Most of Pacific Bell’s residential customers may always see it as just “the phone company” and judge it on the cost of the local service it provides. But the success of the company under its new leadership will depend on a lot more than that.

Sam L. Ginn, who on Friday was elected chairman and chief executive of Pacific Bell’s parent, Pacific Telesis Group, delineated a triple challenge ahead.

“The challenges,” he said, “will be to capitalize on the opportunities of California’s--and the nation’s--high-growth information markets, to reshape the regulatory process to bring it in line with today’s realities and to continue providing the best telephone service anywhere.”

Ginn, 51, succeeds Donald E. Guinn, who chose the company’s annual meeting in San Francisco to make good his vow to retire at age 55. He will remain as a Pacific Telesis director.

Pacific Telesis’ ability to meet the broad challenges outlined by Ginn will depend largely on how successfully its Pacific Bell unit can adapt to a rapidly changing telecommunications market without losing sight of its original mission--providing local phone service. After all, Pacific Bell still generates more than 90% of Pacific Telesis’ annual revenue and all of its profit. And Pacific Bell, too, has a new leader who also foresees change ahead: Philip G. Quigley, 45, who took over as president last September.

“As we move more into a competitive world, we need to change as a company,” Quigley said in an interview in Anaheim last week.

Pacific Bell’s bread-and-butter business remains voice communications, he said, but its future includes transmitting rapidly increasing amounts of computer data and video signals, and this requires a constant struggle to keep up with emerging technologies that are expected to transform the way a good part of America works and, for that matter, lives.

Likely to Change

Despite Pacific Telesis’ proliferating roster of new businesses--which range from cellular radio and electronic paging services to real estate development and the sale of computer systems--Pacific Bell will continue to dominate Pacific Telesis. But it may be a far different Pacific Bell operating in a marketplace in which telephones and computer technology are expected one day to merge.

Since the incorporation of Pacific Telephone & Telegraph Co. in 1906, the struggle was one of keeping up with the telephone needs of a rapidly expanding population. But that challenge was accomplished as a regulated public utility operating under the protective shell of a monopoly.

Following the 1984 breakup of the Bell System, which resulted in the creation of Pacific Telesis and six other regional holding companies to take over American Telephone & Telegraph’s local phone operations, Pacific Bell has lost much of the phone business of 11 of its 20 largest corporate customers, Quigley said, after they chose to build private facilities that bypassed the public network. (Pacific Bell is rarely a complete loser in that, however, since it also leases private lines and provides telephone switching systems.)

With deregulation of long-distance and other information services, such as voice mail and electronic messaging, however, the company finds itself increasingly on the run to keep up with younger, smaller and more sprightly suppliers. Survival thus will hinge on Pacific Bell’s ability to gain flexibility from state and federal regulators in pricing its products and services--especially the Centrex network that handles telecommunications for big users.

“That’s a prerequisite,” Quigley said of the need for pricing flexibility. Prices now are the same for all customers.

Quigley’s success at Pacific Bell will be won or lost on the regulatory battlefield, according to Robert B. Morris III, telecommunications analyst for Prudential-Bache Securities.

“It will be Ginn’s challenge to continue the excellent performance he inherits and to begin to deliver on some of the opportunities (the industry holds) for the future,” Morris said. “It’ll be up to Quigley, primarily, to gain the needed flexibility on the regulatory front for Pacific Bell.”

While local phone companies pursue pricing flexibility, the Federal Communications Commission has asked them to find ways to make their networks equally accessible to all who have electronic information services to sell--including the phone company itself. Under Pacific Bell’s proposal, Quigley said, network service would be “unbundled” into its components; sellers of information services would be able to buy just those elements they need.

“We are trying to create a national standard, but so far open network architecture is still just a concept,” Quigley said.

Service Costs More

Meanwhile, long-distance carriers are pressing regulators to let them compete in the lucrative local-toll market in which Pacific Bell still enjoys a monopoly. But Ginn and Quigley said that such competition cannot yet be allowed. Part of what makes the field appear so attractive is that the prices for these and other optional telephone services, such as call forwarding and call holding, are inflated by more than $3 billion a year in order to keep bare-bones phone service universally affordable.

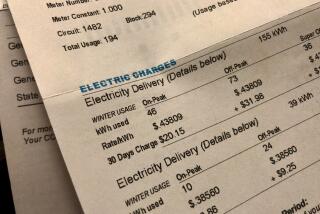

That is how Pacific Bell’s residential customers can be charged a monthly fee of less than $9 for a service that actually costs more than $30, Quigley said.

“What we must do to protect our own interest is not to open up markets to competition before we deal with the cross-subsidy issues,” Ginn said last month.

But as the telecommunications and information worlds gradually merge, Quigley said he expects Pacific Bell to be increasingly challenged by competitors in almost everything it does. If so, would that mean that the concept of a monopoly utility has about run its course?

Not entirely, Ginn replied. “The local loop”--the wires running from a customer’s home to the nearest network switch--might continue to be “carved out” as a franchise area forever closed to competition, he suggested.

“Dial tone may always be subsidized,” Quigley added, “but the other services will move more to cost.” In other words, he said, access will remain low to a telephone network that will offer a lengthening “menu” of services for those willing to pay for them.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.