Mr. Wizards : 2 Named to Prestigious National Academy

- Share via

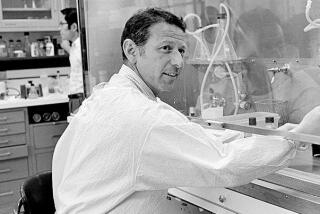

Eugene Roberts is a talkative, grandfatherly mensch who, with his thick mustache and graying, wire-brush hair, looks like a well-shorn Albert Einstein.

In describing aspects of the brain’s molecular operations, the neurobiochemist invokes Ginger Rogers and Fred Astaire, Moses and Michaelangelo.

In contrast, electrochemist Fred C. Anson, who at 6-foot-6 presents an imposing physical figure, is more low-key. Yet, much like Roberts, Anson epitomizes a kind of friendly Mr. Wizard, who knows about the most complicated scientific matters and can take you step-by-step toward understanding them.

Anson of Caltech and Roberts of the City of Hope’s Beckman Research Institute were recently selected for inclusion in the 1,540-member National Academy of Sciences. They were among 60 scientists and engineers the academy added to its number this spring. An academy spokesman said the two were selected because of the body of their work.

“They are quite different men in quite different fields,” said Nobel laureate Linus C. Pauling.

Some scientists, he said, try to act like “they’re so brilliant that ideas just come to them.” What distinguishes these two is that their brilliance is tempered by modesty, Pauling said.

Pauling, long an academy member and the dean of today’s chemists, has known both men for decades and taught Anson freshman chemistry at Caltech. “They are good scientists. They’re both hard-working and this is an important commendation.”

Anson’s work as a teacher and researcher focuses on electrochemistry, a science with applications to an ordinary car battery, a hearing aid or in the fuel cells for spacecraft.

Roberts’ expertise centers on the chemistry of the brain. In particular, his work has applications in the treatment of epilepsy, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases and schizophrenia.

Anson described the essence of his research this way: “You can pose some very simple questions. But what you discover along the way is, more often than not, not what you anticipated when you started out to ask the question.”

At its most basic level, Roberts says, his work resembles that of many other scientists, painters, musicians, writers and philosophers. “I mean really, the questions are all the same: What am I about? What is human life? What is cellular life? We’re all asking the same questions.”

The men, who have loved science since boyhood, have found comfortable scientific home bases where they have spent most of their careers.

Roberts, 68, has worked at the City of Hope since 1954. He also teaches courses in biochemistry and neurology at the USC.

Stayed at Caltech

Except for graduate school at Harvard University and an occasional fellowship abroad, Anson, 55, has remained at Caltech in Pasadena from the time he enrolled as a freshmen in 1950 at the urging of his first physics teacher, John B. Forster of Alhambra’s Mark Keppel High School.

He has stayed at Caltech, Anson says, because the school is unique. “It encourages collaboration between faculty and students and there is a degree of collegiality which is rare in other chemistry departments. We share instruction. We share students. We share ideas. This is the style Linus Pauling set when he was chairman.”

Each man considers Pauling a significant influence. As chairman of Caltech’s division of chemistry and chemical engineering, Anson occupies the position Pauling held for 21 years. Pauling left Caltech in 1963, just after winning a rare second Nobel Prize, that one for his peace work. He had won for chemistry in 1954.

A decade earlier, Roberts first met Pauling when the famous chemist visited the University of Michigan where Roberts was a graduate student.

Picasso Buffs

Anson and Roberts share a common interest--Pablo Picasso. On his office wall, Anson has a print of Picasso’s “Guernica.” Roberts cites Picasso’s genius as an example of the human brain in all its glory. But other than that, two men are very different and their work is unrelated.

Anson is the hometown boy who made good, growing up just south of the Caltech campus, in Wilmar, later incorporated as South San Gabriel. His father was a wholesale paint salesman, and Anson could not have gone to Caltech if he had not received a scholarship from the Los Angeles Times, where he was a carrier.

Roberts was born in Russia three years after the 1917 revolution. His father, a prosperous merchant, fled with baby Eugene and the rest of the family to America’s Midwest, rather than chance death amid Russia’s tumultuous political atmosphere.

In his office at Caltech, with an expansive arched window behind his desk, Anson talked about his process of discovery. “You never know when you’re going to uncover something that’s unanticipated. That’s one of the things that keeps me going. Almost never is it a straight path.”

Focus on Kinetics

Anson describes his field as “figuring out how electricity can be generated from chemicals.” That knowledge has helped scientists develop heart pacemakers and techniques to detect chemicals in humans, animals and bodies of water.

Anson and a group of 12 students are focusing on kinetics, mechanisms and catalysis of electrode reactions. They are conducting experiments to devise ways to speed up the rate of the transfer of a charge between a liquid solution and conductors on electrodes in the solution.

Looking at the Picasso on his wall, which depicts the 1937 bombing of Guernica during the Spanish Civil War, Anson said he likes the painting because of “the story that it tells about war and savagery and inhumanity. It reminds me of the less attractive aspects of the world outside the laboratory.”

As a student at Harvard, Anson did volunteer work in children’s mental health wards. When he came back to Caltech as a professor, he worked with Pauling in trying to understand the chemical nature of mental illness.

Schizophrenia Study

Likewise, Roberts has conducted experiments in an attempt to understand how neurons malfunction to cause schizophrenia. “I feel nothing inconsistent about being intensely interested in cancer as well as schizophrenia.”

In his office in Duarte, Roberts launched into a Socratic-style, free-wheeling discourse. As he spoke, he fished the last Oreo from a packet that was a mid-morning snack.

“Probably the most intelligent people in the world may be illiterate. They might never have seen a skyscraper. Yet they react in an adaptive way. You have a man in the jungle. He sees this leaf is bent. He smells this (certain) smell. He knows whether there is a tiger in this environment and . . . if there is, thinks: ‘I’ll take another path.’ ”

This ability, Roberts says, results from the brain’s sophisticated capability to recognize patterns. He was sitting in a squeaking, swivel chair behind a desk surrounded by wall-to-wall, floor-to-ceiling shelves loaded with scientific journals and books and racks filled with plastic models of molecular structures.

During World War II, he worked on radiation safety studies as part of Manhattan Project, under which the first atomic bomb was developed. He stopped working on the project after the United States bombed Japan. He said he could no longer reconcile that work with his desire to use science to help humanity.

Cancer Research

He then went into cancer research at Washington University in St. Louis. At first, he specialized in cancer research, but by 1949 his research on tumors in mice led him to studies on how nerves in the brain receive and transmit information.

His first significant discoveries involved a substance called gamma amino butyric acid, or GABA. GABA is present throughout the central nervous system of humans and animals, and, as Roberts and other researchers were to discover, its presence in the brain is of particular importance.

GABA influences behavior and emotions in complex ways, Roberts said. It regulates communication between neurons, allowing humans to react to a wide variety of stimuli.

“It’s like a dictionary that increases in size when you need to find more words and decreases when you need to only find a few words.”

Alzheimer’s Help

He is now trying to apply his research to help Alzheimer’s patients restore more balanced behavior.

One key attribute of GABA neurons, he said, is that they function to inhibit. His work shows that an astonishing 40% of the nerves in a human brain are engaged in inhibition. “Why do you need that much? The brain is held in check, but everything is ready to go. It’s like you have a team of lively horses. Unless you kept them reined in, they’d be running. What do you need them reined in for? So at any time you can get them to do what you want and move quickly.”

He compared the relationship between inhibition and excitement at the cellular level to the dance team of Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. Like the dancers whose movements meshed as they swirled, GABA neurons provide for the smooth flow and blending of information to the brain.

Roberts’ eyes widened and his eyebrows darted about as he spoke. “The great ones see patterns, whether they’re great composers or great scientists.”