In the American Experiment, Liberty of Conscience Is the First Liberty

- Share via

America’s number is 1776. Often written MDCCLXXVI, this number appears over and over in American iconography. You will find it on the Great Seal of the United States (on the dollar bill). You will also find it on the tablets held by the Lady of Liberty.

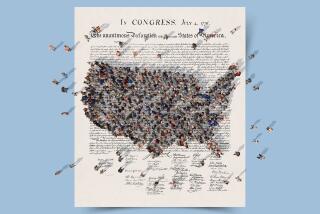

On July 2, 1776, the founders of this nation broke from Great Britain. On July 4, they declared the principles behind their willingness to go to war. “We hold these truths . . . “ they proclaimed. Thus, the United States has never been ideologically neutral. It is built on “truths.”

America began with a creed: “. . . that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; . . . that to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed. . . .” When the founders said “created equal,” they did not mean “created identical.” The same founders also believed that each human person is unique and unrepeatable. For them, “equal” meant a subject responsible for his own actions, ward of no one. Humans are equal in rights. Each is a free person, capable of reflection and choice.

For these principles, they fought a revolutionary war. And they won. And then their experiment began to fall apart--rebellion in Massachusetts, riot in North Carolina, discontent everywhere. The founders (and all Americans) were beginning to look like the laughingstock of the world. They had complained against a mild tyranny, and now seemed incapable of governing themselves even as well as King George III had governed them. They seemed likely to reap anarchy.

Thus the Americans discovered by 1787 that a declaration of principles is not enough. A declaration of rights is not enough. To secure those rights, a government must be instituted--a government that would work.

It would have to work, moreover, for sinners. There would be no use in 1787 in designing a government for saints. Of these, any republic has too few. (And those that it has are rather impossible to live with.)

Recognition of human sinfulness is the beginning of political realism. To design an order worthy of free men and free women, one must design one that will work for sinners. On this Earth, that’s all there are.

The same Creator who endowed men and women with unalienable rights made them in his image. Like their Creator, all humans are meant to be creative.

The two key creative activities are reflection and choice. Reflection: to look again, to consider, to examine alternatives. Choice: to single out a course of action and to lay hold of it. These are the basic capacities of free persons.

Alexander Hamilton caught this point when he wrote in the very first paragraph of Federalist 1:

“It seems to have been reserved to the people of this country, by their conduct and example, to decide the important question, whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.”

In choosing an image for God on the Seal of the United States, the founders chose an eye: symbol of candor, conscience, light. The alert eye is the discerner of alternatives, the detector of possibilities, the organ of enterprise. And above the all-seeing eye, they wrote: “ Annuit Coeptis (Providence) smiles on our undertakings.”

The God of Judaism and Christianity is the God of conscience. Conscience is what humans have most in common with him: light and liberty.

In the American experiment, therefore, liberty of conscience is the first liberty. Humans have dignity because they can reflect and choose. These are the first two imperatives of American life. Reflect. Choose.

Under the American regime, the unreflective life is not worth living. It is, so to say, un-American, a falling off from the American idea.

Under the American regime, not to choose but merely to drift is also to be less of a citizen than one ought to be, less responsible, less brave, less free.

Last week there took place in Williamsburg, cradle of the proclamation of religious liberty in Virginia, the public signing of a new “Williamsburg Charter” on religious liberty. The charter is an important document, not least because it swings emphasis from the negative “no establishment” clause of the First Amendment to the positive “free exercise” clause. It is the latter that gives conscience its creative power. This is a crucial step forward for our time.

Reflect and choose. Liberty of conscience is the first liberty, from which all others flow. No established authority can acquit this responsibility for any one of us. The heart of American citizenship lies in the “free exercise” of one’s own capacity for reflection and choice.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.