- Share via

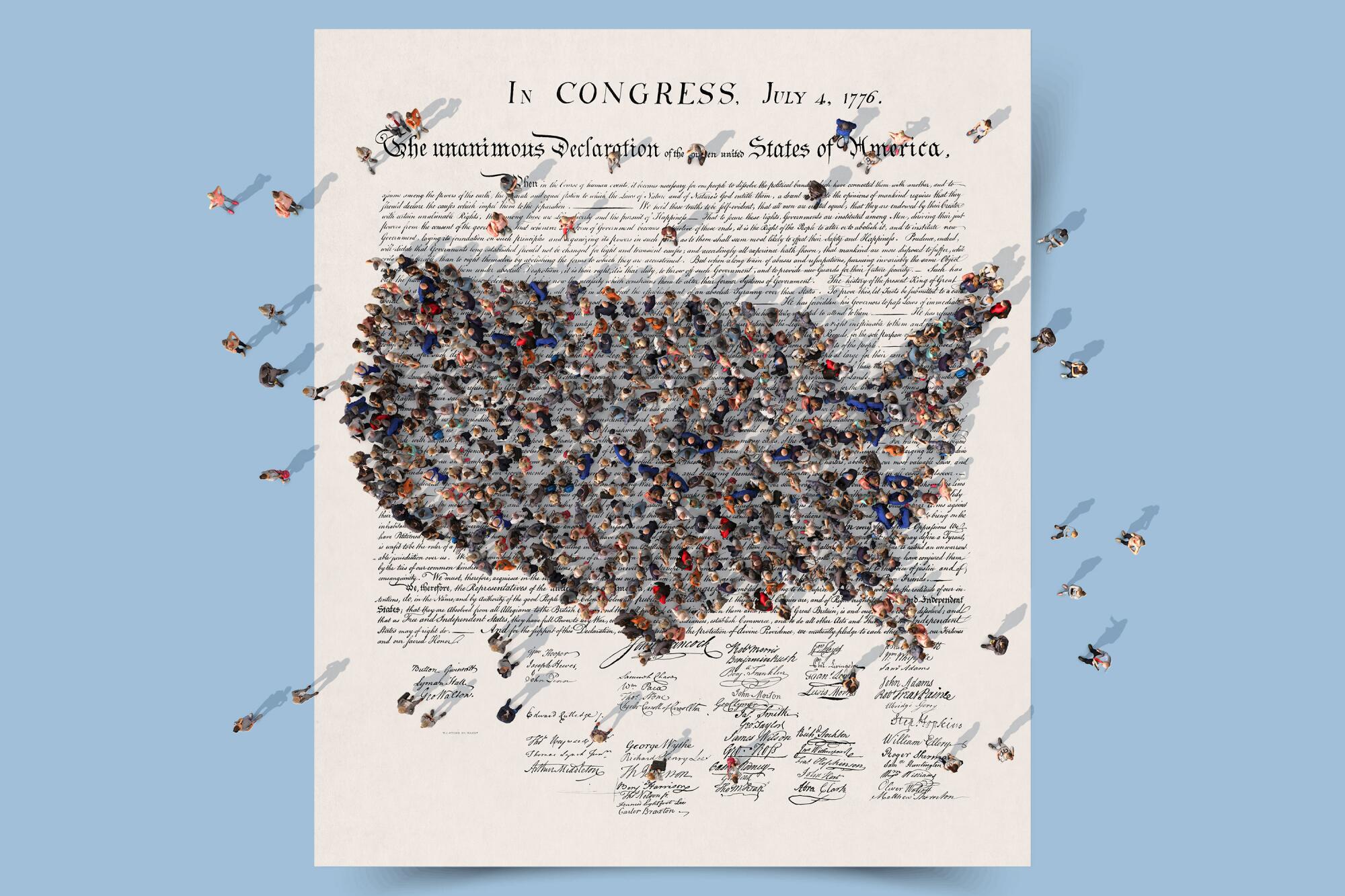

Perhaps no idea has done so much to advance the cause of liberty and equality in the United States as the “right of revolution.” As we celebrate the adoption of the Declaration of Independence this Fourth of July, it’s important to remember the meaning and origins of that political principle, one of the most transformative in American history.

For the founders, the right of revolution did not imply violent overthrow of government. Rather, it was an idea that encompassed the right to resist unconstitutional acts through nonviolent civil disobedience — and, only when this failed after long sufferance, by formal withdrawal from unjust government in the defense of freedom, equality and the right of the people to govern themselves.

This right of resistance against inequality and tyranny is the American way. It is the essence of the American experiment, beginning in the 1760s and 1770s with the colonists’ defiance of the Stamp Act, the Townshend Acts, the Tea Act and the Intolerable Acts; and in the 19th and 20th centuries with the abolitionist movement, women’s suffrage movement, the Emancipation Proclamation, the 13th, 14th, 15th, and 19th amendments, and the civil rights movement; and today with nonviolent fights for racial justice, equal voting rights, LGBTQ+ rights and women’s reproductive rights.

Over five years, I read 1,001 novels to hear the voices that fill this country. These books showed me that the places of American fiction can’t be divided into blue or red states.

The founders, of course, did not create the doctrine of nonviolent revolution against tyranny. They inherited it from British history and from two seminal books, Algernon Sidney’s “Discourses Concerning Government” and John Locke’s “Two Treatises of Government,” published in 1698 and 1689, respectively.

In “Discourses,” Sidney argues that “by nature all men are equal” and that “governments arise from the consent of men.” Consequently, he maintains, the people of a nation, when oppressed by tyranny, are “obliged, by the duty they owe to themselves and their posterity, to use the best of their endeavor to remove the evil.”

Locke, a contemporary of Sidney, handed down the theory of the right of revolution as if it were a mathematical law. Because human beings are entirely sovereign over themselves by preexisting natural right, delegating only a portion of their powers to rulers as fiduciaries, he argues that the people may resist unconstitutional acts whenever a political leader “sets up his own arbitrary will in place of the laws.”

The right of revolution, Locke continues, is a cornerstone of free government because citizens “can never be secure from tyranny, if there be no means to escape it.”

The constitutional reform most on the minds of the founders in 1776 was England’s Glorious Revolution of 1688. In that bloodless overturning of absolute monarchy, William and Mary deposed James II, establishing the primacy of the Parliament over the crown. The next year, Parliament enacted the English Bill of Rights, affirming citizens’ rights of free elections, free speech and no taxation without representation.

In this spirit, the Declaration of Independence is a nonviolent manifesto. It makes no mention of swords, guns or war. Separately, the Continental Congress called upon American patriots to arm themselves, yet only in self-defense of God-given natural rights.

What the right of revolution requires, however, is that the people of a free society never submit to tyranny. As the founders described their Lockean philosophy in 1776, the people should not dissolve political bands “for light and transient causes,” nor without prolonged efforts to reverse acts of injustice through protest and civil disobedience.

The best spin from the 2023 ‘Freedom in the World’ report is that the ongoing decline in rights and liberties is continuing at a slower pace than before.

Yet, the Declaration affirms, “when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same Object evinces a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.”

The logic of the right of revolution gave birth to this nation in July 1776, and it persists today in American resistance to insurrection against democracy, voter suppression, gerrymandering, book banning and the denial of equal rights to people of color and LGBTQ+ people.

It persists in the voice of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who proclaimed in 1963, “One has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws.”

And in the voice of John Lewis, who said in 2018, “Do not get lost in a sea of despair. Be hopeful, be optimistic. Our struggle is not the struggle of a day, a week, a month or a year, it is the struggle of a lifetime. Never, ever be afraid to make some noise and get in good trouble, necessary trouble.”

And in the poetry of Amanda Gorman, who recited on the steps of the U.S. Capitol in January 2021, “Somehow we’ve weathered and witnessed a nation that isn’t broken but simply unfinished. ... We will rise from the windswept Northeast, where our forefathers first realized revolution.”

Eli Merritt is a political historian at Vanderbilt University. He writes the Substack newsletter American Commonwealth and is the author of “Disunion Among Ourselves: The Perilous Politics of the American Revolution.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.