First Transatlantic Crossing Recalled 10 Years Later : On Wings of Eagles, Balloon Sailed Ocean

- Share via

ALBUQUERQUE, N.M. — In a cramped gondola dangling beneath an 11-story helium balloon, with clouds obstructing any view below, the disembodied voice of the radar operator seemed scarcely to be believed.

“You have crossed the coast of Ireland,” the voice told three American balloonists on that still-dark early morning 10 years ago. Larry Newman asked if the message was indeed that which had eluded others for 105 years.

Silence.

Then, crisply, “Sir, my radar is never wrong.”

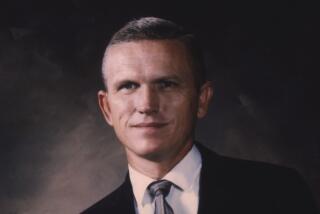

Newman, along with Ben Abruzzo and Maxie Anderson, whooped with joy. Sunburned and weary after five days aloft, the businessmen-adventurers had made the first transatlantic crossing in a balloon.

The three landed their black-and-silver Double Eagle II later that day, Aug. 17, 1978, in a wheat field west of Paris.

Today, Newman is the only one of the three still alive.

Two Died in Accidents

Anderson was killed in 1983 at age 48 when his balloon crashed in a West German forest during a race. Abruzzo, then 53, died in 1985 when his twin-engine airplane crashed shortly after takeoff in Albuquerque.

Newman, now 40 and a commercial airline pilot in Phoenix, said his thoughts often drift back to that summer 10 years ago.

Newman recalled that after the initial jubilation, Anderson went to sleep while he and Abruzzo looked down through the clearing clouds on the lights of Dublin.

The silent 112-foot balloon 15,000 feet up caught sounds that drifted skyward. Newman and Abruzzo could hear dogs barking and trains rumbling along tracks nearly 3 miles below.

“Tears came to my eyes,” Newman said. “I put my arm around Ben--he’d always been somewhat like a father to me. I hadn’t felt that close to another human being for as long as I can remember.”

The men began the flight six days earlier when the Double Eagle II lifted up from Presque Isle, Me., and headed toward Europe more than 3,000 miles away.

Newman says the flight was not without problems, including a clash of personalities.

“Maxie Anderson later stated that he wished he could have flown the flight by himself,” Newman said. “I don’t know what Ben’s feelings were, but I wanted someone to share this with. I didn’t want to be Charles Lindbergh.”

Conflicts Arose

Newman said conflicts arose when Anderson and Abruzzo both began making key decisions.

“Any aircraft can only have one captain, and we had two: Ben Abruzzo and Maxie Anderson,” he said.

But Newman said conflicts were overshadowed by the hardships of the flight in the 12-by-6-foot living space crowded with TV cameras and navigational equipment. Newman’s hang glider dangled beneath the gondola and 5,500 pounds of sand and lead for ballast hung over the sides in bags.

“There were many times the flight was in question,” Newman recalled. “But how close it came to failure at each moment was interpreted different by each of us.”

They lost altitude rapidly at one point when ice chunks crusted on the top of the balloon. They jettisoned valuable ballast. When they dropped to 4,000 feet the ice melted.

Later in the flight they dumped more ballast, including an expensive navigation system that had failed on the second day. They tossed oxygen bottles, anything they could.

Newman said that at one point, a bit delirious from the altitude, he chucked a $4,000 radio--and only later noticed a jar of peanut butter that weighed as much.

Plans were for Newman to fly the glider down once they made it to Paris.

But 400 miles from Ireland, it came down to a choice of dropping the glider, their last oxygen and food, or a propane tank for a heater to battle Abruzzo’s frostbite. The glider went.

Radios also failed during the flight, and the men had to communicate by ham radio.

“The first guy I talked to wouldn’t talk because I didn’t have a license,” said Newman. “And he didn’t believe I was in a balloon over the middle of the ocean.”

Finally, Newman reached an old man confined to a wheelchair in a home for the elderly somewhere in England.

‘Like Good Shepherd’

“His call sign was ‘G4JY.’ I don’t think I’ll ever forget that,” he said. “He talked to me until the last day of the flight. He was like the Good Shepherd.”

Newman said the rough times were offset by the excitement.

A high point, he said, came over Ireland when a jumbo jet relayed a message from the Smithsonian Institution. The museum had asked to display the gondola and balloon in the National Air and Space Museum that houses the Apollo 11 moon ship, Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis and the Wright brothers’ plane.

In the final few hours the men believed they would make it to Paris, where Lindbergh had landed 51 years before after the first solo transatlantic airplane flight. But over Evreux, France, they realized that they could not go on.

The last of the ballast was gone, save for a bottle of champagne. They were 60 miles west of Paris, 3,107 miles and 137 hours from Maine where the helium-packed balloon had taken off.

The swiftly draining balloon envelope carcass and its gondola settled gently to Earth as cheering spectators abandoned their cars along a nearby highway and rushed to the balloon.

Hundreds tried to take a piece of history.

‘Probably Losing Teeth’

“It’s hard to chew rubberized cloth,” Newman said. “People were trying to tear little shreds off, but I think they were probably losing their teeth more than damaging the balloon.”

The French press dubbed them the “new Lindberghs.”

But Newman says the only time he thought about Lindbergh was when the adventurers drew straws that evening to see which would sleep in Lindbergh’s bed at the American ambassador’s residence in France.

Newman and his wife won.

“And I ended up on the floor after 30 minutes because I couldn’t sleep,” he said. “The bed was like a banana. The springs were shot.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.