Commentary : In Politically Lively Ireland, Bush-Dukakis Race Fails to Stir Passions

- Share via

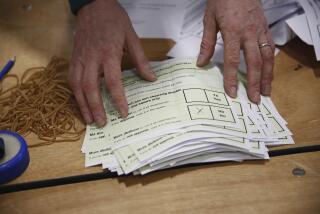

Three hours ago, over a pint of Guinness in Vaughan’s Pub in Clifden, Connemara, County Galway, Republic of Ireland, I used the publican’s Bix pen to punch out the holes on my absentee ballot.

It was a satisfying task, but a lonely one. I was the only one in the bar and, on the radio, the news was bringing no fresh word of the progress of the presidential campaign raging away with increasing vitriol some 5,000 miles to the west.

In Ireland, a politically lively country, such a lack isn’t unusual. For while the Irish appear to love a good political chat, they have reacted to the infrequent and brief stories about the approaching election that have been broadcast on Irish television with a mixture of amusement, disdain and resignation.

American political news often appears at the bottom of the broadcast here, and, with Election Day getting closer, the short visuals have taken on the look of soap opera. Their brevity makes George Bush’s and Michael S. Dukakis’ charges and countercharges--a few days ago the subject was racism--appear to shrink to quick shouts of “Did Not!” or “Did too!”

It all makes the Irish shake their heads. And then change the subject, often to the weather, which they care about and discuss passionately.

It isn’t that they don’t care who makes it to the Oval Office. Many an Irish citizen has reminded me that the President of the United States is considered the most powerful man on Earth. It is that many of them consider that the closing antics of the campaign are not worth much of their attention.

They have said that they consider the postures of both candidates to be insubstantial and politically ingenuous.

“Do you know what amazes me?” asked one young woman after watching the nightly coverage. “It’s that those two are supposedly the two best men for the job in all of the States. You’d think your country could do better than that.”

On another occasion, a middle-aged man told me that the Irish were less concerned with who ends up living in the White House than with who ends up working on Capitol Hill. It was the Congress, he held, and not the President who made the decisions that most affected Ireland’s economy. The President, he said, determines America’s direction, but it is the Congress that often decides where the money goes.

And that is of increasingly strong importance to a people who have relied on a traditionally agricultural economy and who now find themselves, largely as a result of foreign businesses that have established plants in Ireland--many in the south are U.S. electronic and computer companies--depending on foreign money to provide domestic jobs.

Military foreign policy, however, doesn’t appear to be the subject of much discussion. As stormy as this island’s internal affairs have been over the centuries, the Irish have been largely a neutral nation in this century. And, pointed out one young man, a fisherman from County Galway, “Ireland is the safest place you can be in a nuclear attack.”

What the campaign has provided the Irish with is sport. Speculation on the outcome in pubs and elsewhere is occasionally lively, but in the same spirit as the Irish discuss any election: in the same light yet analytical way they might argue about the merits of the play of two All-Ireland hurlers or footballers, or a brace of race horses.

The Irish also can be a fatalistic people, and come by a certain sense of resignation as a result of hundreds of years of tangled and often violent change.

So the final stretch of a campaign an ocean away can produce a gentle smile and a shrug or a solicitous, “Oh, dear, dear . . . “ to a visiting American, while Irish Prime Minister Charles Haughey’s recent hospital stay was worth several minutes of air time on the evening news, including an interview with a hospital official concerning a rumor that Haughey’s heart had stopped briefly (she said it had not).

As I sealed my ballot envelope in Vaughan’s Pub, I remarked to the publican that it looked as if I had just voted for the underdog.

“Well, what else can you do?” she said pleasantly. “You try your best and wait to see what happens, don’t you?”

Which, in the face of the beginning of a new American presidential administration, is what this island nation is doing.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.