Paris Opera: Who’s the Boss?

- Share via

Who should be in charge of one of the most prestigious opera houses in the world? An artist with a multimillion-dollar budget who wants to showcase the greatest musical names of the age? Or a businessman appointed by a Socialist government committed to presenting opera to the masses?

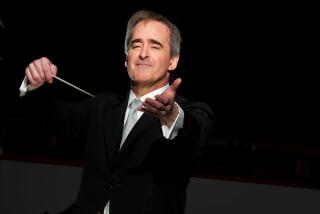

The dispute over the firing of Daniel Barenboim from his post as music and artistic director of the new, still-unfinished Opera de la Bastille in Paris has focused on some of the perennial questions of art versus commerce.

Musicians and adminstrators constantly battle over who, ultimately, sets the priorities for musical organizations, but rarely do their fights break out in the open the way the dispute between Barenboim and Paris Opera Chairman Pierre Berge has this week.

In a phone interview from the Metropolitan Opera house in New York, Bruce Crawford, general manager of the Met since 1986, tried to put the dispute in perspective.

“It’s a very difficult question when you ask what should the relationship between operatic artists and an operatic administration be, because that varies according to the specific situation,” said Crawford, who is leaving the Met to return to corporate life April 1.

The financial situation, Crawford says, is the crucial one here.

“It is my understanding that Barenboim was given $50 millions over the (projected) box-office receipts to spend (on artists and production). That’s very generous, certainly more than other international companies, including the Met, ever receive.

“But, there must be basic agreements about how to spend that money.”

The present brouhaha has been coming for a long time, Crawford observed.

“This crisis was not something that erupted recently, and it’s not wholly a musical one. Since his appointment, Barenboim has been involved in a number of disputes. There has been ferment for a long time.”

In Los Angeles, film composer Lalo Schifrin, who commutes to Paris regularly as music director of the Paris Philharmonic, pointed out that Barenboim’s status as a non-Frenchman has not been lost on the Parisians--Barenboim, an Israeli, was born in Argentina.

“When Barenboim was first appointed,” Schifrin said, “one of his first plans was to reaudition all the orchestral players, with the thought that the Paris Opera orchestra should be open to membership from all over Europe and that only the best players available should be in the orchestra. This was not a popular idea.”

Indeed, Crawford pointed out, anti-Barenboim pamphlets have been handed out at musical events in the French capital for some months now.

But the basic dispute, Schifrin said, remains “quantity versus quality. Berge (chairman of the government-run opera house) sees the mission of the opera as bringing musical theater to the masses. He thinks that, for all the money Berge has been successful in raising, Barenboim should be able to produce 250 performances a year. Opera Bastille should be a ‘people’s opera,’ one the average Frenchman can attend.

“On the other hand, Barenboim, as an artist, wants to raise the prevailing standard of performances, give major artists adequate rehearsal time--often, they will not come unless you guarantee them a certain amount of rehearsal--and bring the world’s best to the company. He thinks the money should be spent on putting on 150 performances every season.”

In Paris, a standoff seems to exist between Barenboim--who says he was never officially notified of his firing and will continue to work until such notification is given--and Pierre Berge, who says he is looking for a replacement for the 46-year-old Israeli conductor to head the artistic side of the new, concrete-and-glass opera house.

Berge, who is also managing director at Yves Saint Laurent luxury goods empire, had charged that Barenboim intended to turn “People’s Opera” into elitist entertainment and had demanded exorbitant fees for himself and his friends.

Barenboim countercharged that personal and political reasons were behind his removal from artistic control of the Opera. Barenboim also insisted that his contract was legal, denying a statement by Berge that it was not binding.

“More and more,” commented Michael Harrison, incoming general director of Baltimore Opera, “the arts are being trapped by this kind of thing. As opera becomes more expensive, the businessmen, for very understandable reasons, want to be more and more involved in the decisions.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.