Wayne Hays, a Scourge of Congress, Dies : Longtime Lawmaker’s Career Ruined by Affair With Staff Clerk

- Share via

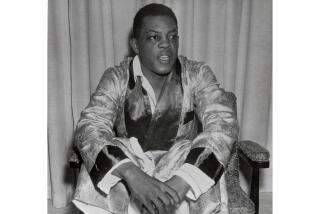

WHEELING, W.Va. — Former Ohio Rep. Wayne Hays, one of the most hated and feared men in Congress whose 28-year career in the House was derailed by an affair with a staff member hired to serve only as his mistress, died Friday. He was 77.

Hays died in the emergency room of Wheeling Hospital about 3 p.m., apparently of heart failure, nursing supervisor Linda Crook said. The Wheeling News Register said Hays had visited a heart specialist in Columbus, Ohio, on Thursday for tests.

Hays, a Democrat, was former chairman of the House Administration Committee, the panel that controlled the perquisites on Capitol Hill and could make life miserable or pleasant for House members.

Described as “the Archie Bunker of Capitol Hill,” Hays took delight in settling personal scores with members who crossed him and won little sympathy when his career was shattered in 1976 by news that he was having an affair with Elizabeth Ray.

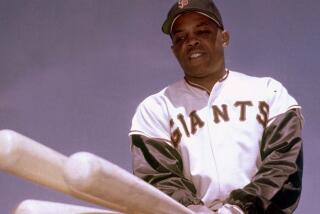

Ray, 33 at the time, had been hired as a clerk in Hays’ office but actually was paid $14,000 a year for two years to serve solely as the congressman’s mistress. She later admitted, “I can’t type. I can’t file. I can’t even answer the phone.”

Hays was renominated in a primary election right after the scandal broke, but soon afterward took an overdose of sleeping pills and nearly died.

The House Ethics Committee began an investigation into Hays’ possible misuse of government funds, prompting the congressman to give up his committee chairmanship. In September, 1976, he resigned from Congress, and the Ethics Committee probe was dropped.

Hays had been married just six weeks before the Ray scandal broke. The previous year he had divorced his first wife of 25 years.

Ray’s disclosures followed an incident in which Hays ordered Capitol Police to escort her out of his office. She said she had gone to his office to ask why she had not been invited to Hays’ wedding when the rest of the staff had.

Ray met with reporters for The Washington Post later that same day. “It’s not that I care so much about (Hays) getting married,” she said, “but it looks bad that I’m not invited. I was good enough to be his mistress for two years, but not good enough to be invited to his wedding.”

On May 25, 1976, in a speech to the House, Hays acknowledged the relationship with Ray, and added, “I hope that when the time comes to leave this House, which I love, Wayne Hays may be remembered as mean, arrogant, cantankerous and tough, but I hope Wayne Hays will never be thought of as dishonest.”

Hays later accused the news media, particularly the Post, of blowing the Ray affair out of proportion.

Hays, born May 13, 1911, returned to his 160-acre cattle and horse farm near Belmont, near the Ohio River. Living with his new wife, Pat, he served on the board of the Citizens National Bank in nearby St. Clairsville.

Though he left politics for a while, politics never left him. He threatened to run for Congress again. He threatened to run for governor.

“I try to do some good for people, but you call the bureaucrats up and they don’t pay any attention if you don’t hold an office,” Hays said. But he said people persisted in calling him up for favors, thinking he was still their congressman.

“I figured if I’m going to do all these things, I might as well hold an office,” Hays later recalled.

In 1978 Hays ran for the Ohio House, where he had already served in the 1940s on his way to Washington. He won the 99th District seat at age 67 and returned to Columbus, mainly as a curiosity.

During his two-year term, Hays was a model of exemplary behavior. He shunned the nightlife and kept an apartment with his wife. He helped write energy and consumer legislation, and battled electric utilities, which he accused of “ripping us off.”

Most of the time, Hays spent the floor session reading the daily newspaper. Every once in a while, he would explode with an acerbic floor speech littered with references to Washington and the past.

He held young lawmakers spellbound with political yarns and was carefully observed for signs of a budding power grab. But Hays apparently was content to have committee input and respond to his constituents’ requests, which were considerable.

“I’ve dealt with bureaucrats in Washington and I’ve dealt with bureaucrats in Columbus, and, believe me, there’s not a damn bit of difference between them,” he once said.

In 1980, Hays demonstrated that he had not learned all the political lessons. Bidding for reelection, he was caught napping by Robert W. Ney, a 26-year-old Republican public safety director from Bellaire, who defeated him the by 500 votes the next November.

“When I realized it was going to be close, it was too late,” a dejected Hays said.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.