The Wealthy Leader of a Shiite Sect Invests in Third World Health Care

- Share via

KARACHI, PAKISTAN — One of the world’s richest men is creating what may be the most ambitious private program anywhere to correct the crippling inequities that deprive people in developing countries from the basic benefits of housing, education, health care and social advancement.

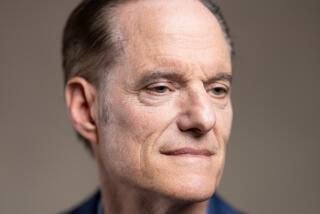

He is a 52-year-old, Harvard-educated British citizen residing in France, Prince Karim Aga Khan, the 49th hereditary spiritual leader of the Ismaili sect of Shiite Muslims, who number 15 million.

For 30 years the Aga Khan (the title means “great leader”) has carefully expanded the programs of social and economic development begun early in this century by his grandfather, whom he succeeded as spiritual leader of the Ismailis in 1957.

The list of social and economic development programs now include 300 educational institutions, 200 health-care centers, diagnostic clinics, dispensaries, five general hospitals and scores of business enterprises self-initiated by poor people in such countries as Pakistan, Kenya, Tanzania, India and Bangladesh. All are funded primarily by Ismaili religious tithings and are available to everyone.

Last month the Aga Khan came to Karachi, Pakistan’s largest and most slum-ridden city, to attend ceremonies at what is planned to become the centerpiece of the Aga Khan Health Services stretching from Africa well into the Asian heartland.

The event was the graduation of the first class of 42 physicians from the Aga Khan University Medical College, a $300-million institution with an ultramodern 721-bed hospital that is by far the best in the nation.

Experts familiar with the problems of training and maintaining health personnel in developing countries fear that here may be another example of sincere intentions destined to falter and finally be ground into inferiority by the same merciless forces that create inequity.

Countless programs funded by international agencies have so withered. But the considerable educational, financial and political forces behind this movement--plus a community-based involvement that is the cornerstone of all Aga Khan development enterprises--raise its chances of succeeding.

There is also the significant impact of a religious sect that is both intense and well directed. Ismailis have been called the “calm corner of Islam.” In the words of the Aga Khan: “It is important that the industrialized world not see the Islamic world as being exclusively the somewhat strident voices which are not representative of the majority.”

Ismailis place a high value on education--particularly of women, who have long been subjugated in many Muslim countries. English and science are the “global intellectual currencies,” as the Aga Khan has said.

Pakistan does not need more doctors so much as a different kind of doctor. The country paradoxically has more physicians than it can now employ--not because the need is lacking but because of economics and the failure of existing government schools to prepare physicians and organize a delivery system that meets public health needs.

Pakistan spends less than 1% of its gross national product on health. The government system has no slots for public health nurses. Rural health centers are either underutilized or overwhelmed with patients but seldom have active programs to teach preventive health.

The Aga Khan’s stated goal is not to replace the government health system but to create programs as models that can be duplicated by other developing countries as well as Pakistan, to meet the needs of all the people. The Medical College, in a unique program, immerses students in the social and living conditions of the masses of poor--who are the bulk of Pakistan’s 100-million residents. From virtually the first day of class, each student is assigned to spend 20% of his or her five school years among Karachi’s poorest residents or in backward villages designing and running health programs.

It is there, say faculty members, where future doctors will learn the causes--mostly preventable--of infant and maternal mortality, malnutrition and infectious diseases that curb economic development and make life insufferable. The official infant mortality rate is 126 deaths in the first year for every 1,000 live births--more than 10 times the U.S. rate--and in many areas of the country the rate is far higher.

But the university is not satisfied trying to meet only primary needs. In what some see as a threat to maintaining its community health program, the Medical College has also decided to provide the specialized training required to perform high-tech procedures typical of health care in developed nations.

While agreeing with that goal, the dilemma, said Dr. Jack Bryant, an American who heads the department of community health services, “is that the largest needs of Pakistan will be met mainly through community-based health services in poor and remote settings, whereas the largest part of the training of the students takes place in an elegant setting where technology is supreme.”

A concern is that students--as has occurred in the United States--will be lured away from working to meet critical community needs by higher earnings in more sophisticated pursuits, and that such conflicting human drives will hamper efforts to remedy health problems that afflict more than half the world’s 5 billion people.

One hope lies in the network of educational and economic development programs fostered by tithes and gifts from faithful Ismailis to the Aga Khan. A key feature--and one of the firm tenets of all community development--is that the incentive to raise living standards must spring from the poor in the slums and rural villages, rather than from outside imposition. A grass-roots philosophy pervades all of the Aga Khan programs.

Before any health program is begun in a city slum or a rural village, leaders of that community are consulted and asked what they see as their most pressing problems. Eventually they choose several residents to attend basic training courses and become that community’s own health workers. Once trained, these workers are contacted frequently, to be consulted, resupplied with simple drugs--and with encouragement.

From these communities many future doctors, nurses and students are expected. The theory is that such students are the most likely to return to the villages to work.

Mumtaz Mughan, a 1988 graduate of the university nursing school, was born in the Gilgit region of Northern Pakistan among the majestic snowcapped Karakoram Mountains not far from China. Today she is the community-health nurse in Singul, a village where Aga Khan Health Services has built a satellite health center that serves perhaps 10,000 persons living in villages strung along the Gilgit River Valley.

“I could make more money if I stayed in Karachi, but I came back because I wanted to help,” she said. Her sentiment echoed many faculty members who returned from greener pastures abroad to help build a better health system in their native land. Most of the full-time faculty of 140 are Pakistani doctors who have returned home after years of training and working in Britain, Canada or the United States.

Dr. Halfdan Mahler, former director of the World Health Organization, captured the spirit pervading the program with a Chinese adage he cited in an address to new graduates:

Go to the people.

Live with the people.

Learn from them.

Start with what they know.

Build on what they have.

When the task is finished,

The people will say,

“We did it ourselves.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.