Biotech Detective Scores Coup : Amgen scientist spent years searching for the key to producing EPO.

- Share via

One morning before dawn aboutseven years ago, George Rathmann drove to his office in a Thousand Oaks industrial park to catch up on his work.

Rathmann, chairman of Amgen Inc., noticed that the lights were on in one of the biotechnology company’s laboratories and concluded that a careless worker had forgotten to shut them off. So he strolled over to the building to do it himself.

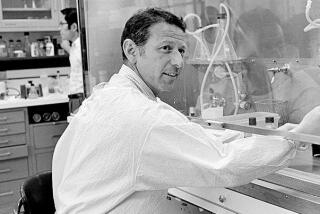

But inside the laboratory, Rathmann recalled, was Fu-Kuen Lin, a Taiwan-born scientist with a Ph.D. in plant pathology who had been hired a year earlier after answering a help-wanted ad in a science magazine. Lin, Rathmann discovered, had been working through the night on what had become his personal obsession--finding the genetic blueprint for erythropoietin, a protein manufactured in the kidney that stimulates the production of red blood cells.

In the years since then, erythropoietin, or EPO, has emerged as one of the most promising drugs developed by the nation’s fledging biotechnology industry. On Thursday, the Food and Drug Administration gave Amgen the go-ahead to sell EPO, making it available to thousands of anemic people suffering from chronic kidney disease who otherwise would need frequent blood transfusions. More than any single person, Lin, now a top-level Amgen researcher, is responsible for the breakthrough.

“He has an extraordinary energy level and incredible persistence,” Rathmann said.

Behind the news of the FDA approval is a story of an often lonely struggle Lin endured to solve a genetic Rubik’s Cube. The task was so cumbersome and frustrating that it has been compared to searching through 90 editions of the Encyclopedia Britannica to find a single sentence.

Set a Deadline

The fifth of seven children born to a Taiwanese herb doctor, Lin, 47, toiled for more than two years to unlock the genetic combination to EPO before making a breakthrough in mid-1983. All the time his scientific reputation, as well as Amgen’s reputation in the young biotechnology industry, was on the line.

Rumors abounded that competitors had done what Lin failed to do. Rathmann once said that if more promising results weren’t achieved in 60 days, the project would be scrapped, although he now says he mainly said it to motivate people. Still, the talk among some people at Amgen was that working with Lin on the EPO project was tantamount to career suicide.

“You could feel the people try to distance themselves from the project,” Lin said. “Even my assistant was told by the other associates, ‘What a dummy you are to work with this guy on a project that is going nowhere.’ ”

Lin rarely saw his wife, two young sons and infant daughter while trying to solve the puzzle. Lonely nights in the laboratory were sometimes filled with the gentle sound of hymns coming from a Christian ministry group that shared the Thousand Oaks building where he had his laboratory, and Lin often worked into the early morning.

“People were wondering if it was going to kill Lin. They were joking about EPO being a graveyard for scientific careers,” said Philip J. Whitcome, Amgen’s former director of strategic planning who now is president and chief executive of Neurogen Corp., a start-up biotechnology company in Branford, Conn.

Born in Keelung, a port city in Taiwan, Lin moved to the United States in the late 1960s to earn his doctorate at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign under the late David Gottlieb, an internationally known microbiologist. Gottlieb became Lin’s mentor, sometimes referring to him affectionately as his “grand-student.”

As with those of many young academics, Lin’s career was a nomadic one that involved moving from university to university and spending valuable time digging up funding for projects that instead could have been devoted to research. After receiving his doctorate at Illinois in 1971, Lin and his family moved to Purdue University, the University of Nebraska, Academia Sinica in Taiwan, Louisiana State University and Medical University of South Carolina. In August, 1981, Lin joined Amgen to work on the young company’s EPO project.

Looked for Gene

EPO is a protein produced by the kidney that stimulates immature red blood cells. First identified in 1906, scientists tried unsuccessfully for years to purify EPO in a laboratory by extracting it from blood, tissue or urine. But the amounts contained in those substances are so small that the effort was about like trying to mine an ocean for the gold contained in it.

Lin’s task was to identify and isolate the gene that encodes human EPO. An EPO molecule can be pictured by imagining a string of more than 160 colorful, plastic beads similar to the multicolored ones young children play with that snap together end to end. Each of the “beads” represents a building block, called an amino acid. By identifying the structure of the molecule, Lin was able to get a clue as to the set of instructions, or gene, within a human cell that directs the production of the EPO protein.

Once that was done, Lin made probes composed of building blocks contained in the EPO gene. Those probes would enable him to identify and isolate the gene for EPO from all of the other genes and genetic information contained in a human cell, a feat Whitcome compares to “finding a sugar cube in a lake one mile wide, one mile long and one mile deep.”

After two years of painstaking work and unsuccessful experiments, Lin narrowed his search to one of 256 possibilities and ultimately solved his puzzle, thus “cloning” the EPO gene. Once that was done, the gene was spliced into cells that came from Chinese hamster ovaries, turning them into microscopic factories that produce EPO.

All the time pressure on Lin was building, in particular because it was known that other companies were working on their own EPO projects. One rumor was that biotechnology rival Genentech had succeeded. Another was that rival Biogen had done it. Some began to doubt whether Amgen would succeed.

Self-Esteem Suffered

“There were many voices that said maybe we can’t solve EPO. Maybe it’s too difficult a problem,” Whitcome said.

Lin said that, as the project plodded along with little to show for it, his self-esteem suffered. “People look on you like you are a dummy or a failure. They don’t know how tough it is. In science, you probably have 90% frustration and 10% success,” Lin said.

Lin is described by colleagues as stubborn, which he acknowledges. But, he said, he always believed that he was right.

“A scientist dissolves his career into nothing if he does not succeed,” Lin said. “All I wanted to do was succeed.”

MAIN STORY: Part I, Page 1

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.