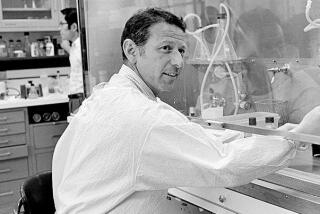

Controversial Nobel Laureate Shockley Dies

- Share via

Nobel Prize-winning physicist William B. Shockley--whose breakthrough work on the electronic transistor was overshadowed by his inflammatory views that blacks are genetically inferior to whites--has died at his home on the Stanford University campus, university officials announced Sunday.

Shockley, who once proposed that the “genetically inferior” be paid for voluntarily undergoing sterilization, was 79 when he died Saturday from cancer of the prostate.

He shared the 1956 Nobel Prize for physics with John Bardeen and Walter H. Brattain for their work at Bell Telephone Laboratories in developing the transistor, a device providing the underpinning for many 20th-Century innovations in electronics.

Although Bardeen and Brattain are credited with inventing the transistor, Shockley was recognized for fathering it by advancing the hypothesis and pointing the way.

The transistor, completed by Shockley and his team in 1947, made the vacuum tube obsolete. Its direct descendants are the brain centers on devices ranging from the space shuttle to videocassette recorders, from calculators to computers.

Organized Firm

After leaving Bell Labs in 1954, Shockley organized a semiconductor company that led to development of Northern California’s Silicon Valley. Employees who went their independent ways after first working for him were later involved in developing the integrated circuit and microprocessors.

But Shockley’s role in the century’s electronics revolution was largely obscured by his incendiary views on race, genetics and intelligence. He went from being a physicist with impeccable academic credentials to amateur geneticist, becoming a lightning rod whose views sparked campus demonstrations and a cascade of calumny.

Although he had no degree in genetics, he devoted the last two decades of his life to advancing his philosophy that intelligence is genetic, that blacks are genetically inferior and as a group could not be as bright as whites.

He called his philosophy “retrogressive evolution,” suggesting that blacks, whom he deemed intellectually inferior, were reproducing faster than what he considered intellectually superior whites.

Although one of his sons earned a Ph.D. in physics from Stanford and his daughter graduated from Radcliffe, Shockley once said, “my children represent a very significant regression” caused by “my first wife--their mother--(who) had not as high an academic-achievement standing as I had.”

Shockley regarded his work on genetics as more important than his work on the transistor, and his wife said he continued to draft papers and analyze data connected with his controversial views until a few days before his death.

In a 1980 interview, he told Playboy magazine that the “major cause for American Negroes’ intellectual and social deficits is hereditary and racially genetic in origin and thus not remediable to a major degree by improvements in environment.”

‘Genetic Disadvantage’

He also said that “the evidence is unmistakable that there is a basic, across-the-board genetic disadvantage in terms of capacity to develop intelligence and build societies on the part of the Negro races throughout the world.”

Shockley’s racial views resulted in many of his fellow scientists abandoning him, while others held him up to ridicule for attempting to go beyond his field of expertise.

In 1973, Leeds University in England withdrew its offer of an honorary degree to Shockley over his proposal for implementing a “voluntary sterilization bonus plan,” under which people with an IQ below 100 would be paid a cash sum if they agreed to be sterilized.

Shockley said that if the university had withdrawn the degree “because I suggested as a ‘thinking exercise’ a voluntary sterilization bonus plan that might reduce the number of babies born with genetic millstones hung around their necks, then faith in the power of intelligence to solve humanity’s problems has fallen to new depths in academia.”

Under Shockley’s proposal, non-taxpayers with an IQ below 100 would have been paid $1,000 for each of their IQ points under 100 if they agreed to be sterilized. Such an intervention in the gene pool was necessary, he argued, to curb what he called “dysgenics,” overbreeding among the “genetically disadvantaged.”

In 1980, Shockley became the first Nobel laureate to publicly state that he had contributed to an Escondido sperm bank set up to pass along the genes of so-called “geniuses.”

Four years later, he won $1 in damages from a federal court jury in Atlanta, which found that he had been libeled by an Atlanta Constitution newspaper column that compared his theories on genetics with experiments on human beings in Hitler’s Germany.

Ph.D. at MIT

Shockley was born Feb. 13, 1910, while his family was in London, where his father was a mining engineer. He was brought to the United States at age 3 and grew up in Southern California.

After graduating from Hollywood High School in 1927 and Caltech in 1932, Shockley earned a teaching fellowship at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he completed his Ph.D.

In 1936, he joined the technical staff at Bell Labs in Holmdel, N.J., just as the laboratories had decided to try to find a solid-state semiconductor replacement for the vacuum tube amplifier, invented by Lee De Forest in Palo Alto in 1907.

In 1939, Shockley began work on semiconductors, solid devices that carry the flow of electricity more slowly than a conductor, such as copper, but more quickly than an insulator, such as glass, making it easier to control.

War Interrupted Work

The work was interrupted by World War II and was not undertaken again until 1945, when Bardeen joined Shockley and Brattain.

By that time Bell Labs could demonstrate a radio without tubes, but the device was commercially useless. But the idea struck Shockley, and others at Bell, as a good metaphor for what they sought. The search, however, led from one failure to another.

“A basic truth that the history of the invention of the transistor reveals,” Shockley said later, “is that the foundations of transistor electronics were created by making errors and following hunches that failed to give what was expected.

Shockley was to later call the process “creative-failure methodology.”

After some experimentation, Shockley’s team settled on silicon and germanium as semiconductor candidates. Both elements impede the flow of electricity if they are purposely contaminated with other materials, such as arsenic and boron.

A ‘Magic Month’

In what Shockley later called the “magic month” of November, 1947, the team found themselves uncovering new scientific “facts” in a series of discoveries that dramatically expanded the knowledge of those elements and their reaction to electricity.

In December, Brattain used a wedge-shaped piece of plastic to press two narrowly spaced, parallel line gold contacts 1/200th of an inch apart against a block of germanium. When an electric signal was introduced to the germanium through the wires, the signal was amplified.

The transistor was born. It was a crude device, but it was clear that if the transistors could be manufactured reliably in large numbers, their applications could prove endless.

Shockley returned to Palo Alto to start his own company, but two years later eight of his best researchers broke away to form Fairchild Semiconductor and launch the Silicon Valley.

The group--Shockley called them “the Traitorous Eight”--included Robert Noyce, who helped invent the integrated circuit, and Gordon Moore, who later invented the microprocessor. Noyce and Moore eventually founded Intel Corp.

In the wake of the firestorm his genetic theories generated, Shockley began avoiding the media--agreeing to be interviewed only if the reporters submitted to IQ tests, among other conditions. After taking such a test, reporter Syl Jones, who is black, was granted an interview and arrived at Shockley’s home with a photographer, who was white.

“Shockley instinctively reached to shake the photographer’s hand with the greeting, ‘Hello, Mr. Jones,’ ” the reporter later wrote. “It was a wrong guess that seemed to stagger him. Obviously stunned by my blackness, he insisted that I submit to one final test, concocted on the spur of the moment, concerning the application of the Pythagorean theory to some now long-forgotten part of his dysgenic thesis.”

In addition to his wife, Emmy, Shockley is survived by two sons, William and Richard; a daughter, Alison Ianeli, and a granddaughter.

No services are planned.