Mighty Tiwanaku : Ancient City Yields Hope for Bolivia

- Share via

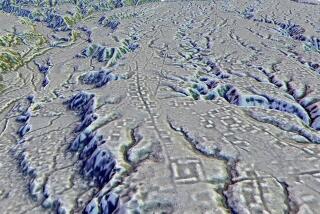

LAKAYA, Bolivia — Rectangular wrinkles in the earth form crosshatch patterns across miles and miles of the broad pampa that slopes gradually into Lake Titicaca near the village of Lakaya. For centuries, the people of Lakaya did not know exactly what the patterns meant, what use they might have had in the ancient days of “the grandfathers.”

“We thought ‘the grandfathers’ made them that way,” said Bonifacia Quispe, a resident of Lakaya, “but we didn’t know how they worked.”

Now scientists have come to dig among the patterns, measuring and studying them. They have discovered that the crosshatched furrows formed a vast series of drainage and irrigation canals, an elaborate network that served one of the most sophisticated and productive agricultural systems ever developed in ancient times.

Little-Known Empire

The system was part of the once-mighty but now little-known empire of Tiwanaku (also written as Tiahuanacu, and pronounced tee-wah-NAH-koo). For more than 1,000 years, the Tiwanaku civilization dominated an Andean area as large as California with a population of millions. Master stonemasons, the Tiwanakans also built a monumental capital that archeologists only recently have begun to systematically explore.

Tiwanaku’s agricultural expertise was lost for centuries after the empire suddenly collapsed between AD 1150 and 1200. But rediscovery of the ancient technology is raising hopes that the prosperity of the Tiwanakans will return to their hard-pressed inheritors.

With the help of scientists and agronomists, Quispe and other Lakaya residents are reclaiming parts of the system and cultivating crops in the same way “the grandfathers” did a thousand years ago. The results so far have been spectacular, with potato yields seven times the national average.

A few miles away, on the other side of a rough ridge, archeologists are speeding up excavation of the Tiwanaku empire’s capital, once a sparkling city of intricately carved statuary, lavish temples and majestic pyramids. The work has brought a wealth of discoveries.

Complex Sewer System

For example, the city had a complex underground sewer system built with finely fitted stone to carry waste water away at precisely calibrated grades.

“To me, that’s the mark of civilization of any society, a running sewer system,” said Alan Kolata, an archeologist from the University of Chicago.

Tiwanaku existed centuries before the more famous Inca empire but in many ways was more advanced in its engineering and craftsmanship.

“In terms of dominating rock and water, I don’t see anyone who has done it better,” Kolata said.

As many as 100,000 people lived in the capital. Only a small fraction of it has been excavated from the deep sediment of centuries.

“This is the last great capital of the ancient Americas that’s never been explored systematically, and now we are finally doing it,” Kolata said. “At its zenith, it was the most important, most powerful, most influential city in South America.”

Kolata, 38, has been digging at Tiwanaku every year since receiving his doctorate from Harvard University a decade ago. He is general director of the Tiwanaku Archeological Project, which has explored more of the ancient city and its surroundings in the past few years than all previous projects had done this century.

Tall and broad-shouldered, Kolata works closely with project co-director Oswaldo Rivera, 42, a slightly built official of Bolivia’s National Institute of Archeology.

The two archeologists agree that the success of Tiwanaku was based on an agricultural system that could feed an empire while freeing thousands of city dwellers to develop skills as engineers, scientists, artisans and managers. And they both voice optimism that the agricultural system can be revived to bring prosperity back to the Altiplano, Bolivia’s high Andean plains.

Lowest Per Capita

More than 12,500 feet above sea level and ringed by snowcapped mountains, the Altiplano is arid for half the year, a harsh and withered motherland for its impoverished natives. The average annual income for Altiplano inhabitants is far lower than the national per capita figure of less than $700, the lowest in South America.

Today’s conditions contrast dramatically with the prosperous heyday of the Tiwanaku empire.

According to American hydrologist Charles Ortloff, who is working on the project, the Tiwanaku field canal system successfully managed the flow of ground water so that the water table under planted fields was never too high or too low for the crops being grown.

Potatoes, other tubers and grains were planted on raised fields, each about the size of a football field’s end zone, flanked by finger canals connected to main canals that drained into Lake Titicaca. The earth to elevate the fields came from digging the canals.

System Drained Excess Water

In the wet season, when rains are sometimes unpredictably heavy, the hydraulic system drained off excess water that could ruin crops. In the dry season, it distributed water from springs and rivers to fields where the water table was low.

“This is the only civilization that we’ve ever found on earth which has this particular system,” Ortloff said.

Ortloff, 52, wears a weathered leather jacket and an Indiana Jones hat with a wide brim. He has been studying early South American hydraulic technology for 14 years.

Algae and other aquatic plants grew in the canals, decaying to create a thick lining of dark sludge. During the day, the sludge’s energy-absorbing darkness helped the water store the sunlight’s heat, which was slowly released into the air on cold nights, warding off frosts that could damage crops. Shoveled onto the fields, the sludge also served as a rich organic fertilizer.

The main drainage canals, lined with cut stone, were designed to carry off large quantities of water from rainstorms. Ortloff said the Tiwanaku hydrologists tamed the hydraulic jump, a physical phenomenon in which the energy of fast-flowing water rises in high waves when the flow is slowed. The waves can destroy a canal if its slope and shape are not perfectly calculated to prevent them.

Sophisticated Hydraulics

“It is extremely sophisticated hydraulics,” Ortloff said.

For the past three years, agronomists and other experts headed by archeologist Rivera have been working with peasant farmers to revive the raised fields. Last year, a newly formed “mothers club” headed by Quispe joined the effort, reclaiming and farming six acres.

“It is a good system for producing potatoes,” said Quispe, 30, as she stood by her home on Lakaya’s central plaza, a barren square surrounded by wall-to-wall one-story houses. Wearing a full green skirt and a dusty bowler hat, she spoke through an interpreter in Aymara, a language used in Tiwanaku times.

Quispe said that the area’s common method of farming on unirrigated hillside plots “only gives a few potatoes.” The reclaimed Tiwanaku fields, on pastureland previously considered too boggy for crops, produces bigger potatoes in much larger quantities.

“I am proud of ‘the grandfathers,’ ” Quispe said with a shy smile.

On 30 acres of Tiwanaku raised fields that have been farmed so far, the average yield has been 17 metric tons per acre, according to a study prepared by Rivera. That is seven times the Bolivian national average of 2.4 tons.

New Goals Set

For the current planting season, which is now beginning, Rivera said he hopes to put 80 acres of rehabilitated fields into production. The goal is 225 acres for 1990 and 375 acres for 1991.

He said that the area’s ancient residents used the raised-field system to farm 400 square miles or more around Lake Titicaca. By Rivera’s calculations, the annual harvest on that area would produce more than double today’s national harvest if it were cultivated with the raised-field technology.

This year, the reclamation project will begin alternating grain and vegetable crops with potatoes, getting two harvests a year from the same land, as Rivera believes Tiwanaku farmers did.

Alternating crops helps replenish soil nutrients and prevent plant diseases from reaching plague proportions. The raised-field system also protects the land from erosion by water and wind. Rivera said this kind of “agro-ecology” was part of the ancient culture’s relationship with what Altiplano Indians call Pacha Mama, or “Mother Earth.”

“The Tiwanaku people revered Pacha Mama because they really understood the processes of nature,” he said.

Uncovering the Splendor

While the Tiwanaku Archeological Project has been helping to reclaim the agricultural system, it also has been uncovering the buried splendor of the Tiwanaku capital. About 90 workers, directed by 11 archeologists and three botanists, are digging at more than a dozen places in the ancient city’s 2.5-square-mile site.

“We have the biggest excavation going in South America,” Kolata said.

Until two years ago, archeologists had unearthed only a small section of the stonework at the base of the city’s biggest monument, the Akapana pyramid. Largely covered by a heavy mantle of sediment, Akapana still looks like a barren hill, but crews are digging at six places on the structure.

Underneath they have found magnificent earth-filled stonework rising in seven staggered levels to a height of more than 50 feet, drained by an internal system of stone ducts.

“It is the largest single man-made stone structure in the Andean highlands in terms of volume and amount of stonework,” Kolata said. “It may be a representation of a sacred mountain with water flowing out through the mountain.”

Human Bones Found

One of the most interesting and puzzling recent discoveries in the pyramid is the bones of dozens of dismembered human bodies clustered at different points along the structure’s base. Linda Manzanilla, a Mexican archeologist working on the project, said the bones were not cut or broken, indicating that the bodies had been taken apart after death.

“They could have died from a number of causes,” she said. “I would prefer not to call them sacrifices so far.” She speculated that they could have been bodies of disease victims placed by the pyramid in a kind of ritual offering.

Archeologists also are digging at another pyramid, the three-tier Pumapunku. The work, which began this year, is the first major excavation on the pyramid.

In May and June, diggers turned up one of the most significant discoveries yet made at Tiwanaku, a series of about 50 hand-sized copper alloy clamps cut into adjoining pieces of stone to hold them together.

Similar clamps have been found in ancient Greek and Egyptian stonework, but Kolata said, “This is the only place in the entire Americas where they used metal to clamp blocks together. The Incas never did this metal clamping business.”

160-Ton Stones

Among Pumapunku’s ruins are the biggest stones in Tiwanaku, weighing up to 160 tons each. Kolata and other archeologists speculate that they were painstakingly brought seven miles into the city by huge work gangs rolling them on logs or spherical stones like large ball bearings.

Using archeological evidence and his imagination, Kolata describes Tiwanaku as a bustling and glittering city laid out around the imposing pyramids. Walls of stuccoed adobe were painted in bright blues, greens, oranges and reds. Carved stone friezes and murals bore gold plating, now long gone.

Debris from digs now being analyzed indicates that Tiwanakans ate well, with a varied diet of potatoes, grains and llama meat, supplemented by abundant fish and waterfowl from the canals of their agricultural system.

The city’s royal and priestly elite wore gold diadems and masks. Their turbans, tunics and short-legged pants were of finely woven and brightly dyed cotton or wool from domestic llamas and alpacas. The best tunics glittered with gold and silver bangles.

The temples and luxury homes had running potable water, brought in by aqueduct and covered stone ducts, and an underground sewer system for carrying off waste and rainwater. The sewer lines, made of closely fitted sandstone slabs, were packed in red clay for waterproofing.

Excellent Engineering

Last year, excavation revealed that secondary sewer lines from buildings feed into main lines with slopes at less than a 3% grade, which would meet the plumbing code for many U.S. cities.

“They maintained a perfect grade to get the flow out to the river,” Kolata said. “It’s truly an amazing system.”

To fully map the sewer system, Kolata said he needs penetrating radar equipment, which would cost about $100,000.

Kolata said a broad, shallow canal extended 10 miles from the lake to the capital. The city was flanked on three sides by a moat estimated to have been at least 10 feet deep, 30 feet wide and at least a mile long.

The moat may have been part of the drainage system, or something else, Kolata said. “There is a great water cult in the Andes. It could be religious, to prevent evil spirits.”

The Tiwanaku civilization was first formed from various tribes spread across the Andean highlands, emerging as a recognizable cultural entity by 300 BC. The empire reached its highest level of development between AD 400 and 700--fully seven centuries before the beginning of the larger but much shorter Inca period.

The Inca empire had existed less than 200 years when it fell to the conquering Spanish in the 1530s. Archeologists say much of the Inca civilization was based on the culture and technology inherited from Tiwanaku, although the Incas are often given credit for Tiwanaku highways and other works.

Linked by Highways

The far corners of the Tiwanaku empire were linked by a network of highways that carried caravans of llamas, the Tiwanaku pack animal, to the Pacific Coast and to heavily forested Andean foothills. In some stretches the highways had stone paving, retainer walls, drain gutters and even culverts.

Kolata said the Incas imported descendants of Tiwanaku stonemasons to work on the Incan capital, Cuzco, and the sacred city of Machu Picchu, both in neighboring Peru. Machu Picchu is famous for its spectacular mountaintop setting, but Kolata said that it is no match for the city of Tiwanaku.

“Tiwanaku is clearly a much more important city,” Kolata said. “All of Machu Picchu would fit into a small corner of Tiwanaku.”

Tiwanaku, of course, is still largely invisible. To dig it out, Kolata and Rivera are now spending $200,000 a year. Robert S. Gelbard, the U.S. ambassador to Bolivia, is an enthusiastic fund-raiser for the project.

“The historical and archeological importance of it is extraordinary,” Gelbard said. “It makes sense to put money into what will eventually be a major worldwide tourist attraction.”

But even with unlimited funds, some of Tiwanaku’s secrets will never be known. Because it did not have a written language, the empire left no recorded history, no manuals on its technology, no social or religious records.

“There must have been great events, individual rulers who did impressive things, but it’s lost to us,” Kolata said.

Empire’s Collapse a Puzzle

A key piece of knowledge about Tiwanaku that may soon come to light is how the empire suddenly collapsed. Some theories attribute the fall to an invasion by barbarians from the area of Chile, but Kolata and Rivera say the most likely cause was a deep and prolonged drought that could have rendered the raised-field agricultural system useless.

Limnologists--scientists who study successive layers of the earth’s sediment for clues to life and climate conditions in the remote past--have taken core samples down to the year 2000 BC and are now analyzing the material bit by tiny bit. Kolata said the results, expected in two or three years, should be revealing.

“We can put all the factors together and we can really nail the collapse,” he said.

Whatever the cause, he said, it seems clear that the Tiwanaku people abandoned their shining city and went off to the Andean hills, where they lived in smaller and more primitive enclaves. The empire broke up into kingdoms that fought among themselves until they were united again by the Incas more than two centuries later.

When the Spanish conquered the Incas, the glory of Tiwanaku was a fading legend, and the empire’s agricultural breadbasket was a far-flung landscape of oddly wrinkled pampa.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.