The Wonders of Voyager

- Share via

What a wonderful and various place the solar system turns out to be. The moons and planets Voyager 2 and its robotic comrades have shown us are stranger and more beautiful than even the cleverest theory could have envisioned. And how unexpected that mankind’s first great reconnaissance of his world’s most distant neighbors should be directed from Pasadena. To those who thought they could foresee how planetary exploration would be accomplished, that must seem as curious as an ice volcano.

In fact, the epochal amalgam of ingenuity and curiousity that has flourished in the shadows of the San Gabriels has put the scientists of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in the first rank of our species’ great explorers. They have again demonstrated that exploration’s most engaging aspect is that it subverts not only our belief in what the facts are, but also our idea of what they ought to be.

Take, for example, the conventional predictions that when Voyager arrived at Neptune, it would find a world made sluggish--or even frozen and dead--by its distance from the sun. But, as we now know, stately blue Neptune is a dynamic world with a tumultuous atmosphere through which vast storms swirl. Its fascinating satellite, pearlescent Triton, has been revealed as a world on which volcanism is even now occurring. In the known solar system, only the Jovian moon Io and Earth itself share that attribute.

The scientists at JPL, however, think that Triton’s volcanic processes are of a different sort. While the Tritonian surface has a temperature of 370 degrees below zero Fahrenheit, the moon’s subsurface temperature is thought to be almost that much above zero. At that point, the nitrogen, which is a major component of Triton’s surface and atmosphere, becomes liquid. One theory has it that the seasonal warming which occurs as the moon accompanies Neptune on its 165-year-long orbit of the sun, triggers eruptions of that liquid nitrogen. Once it breaches the surface, the nitrogen freezes and Triton’s 200-mile-an-hour winds carry it across the surface in plumes more than 40 miles long. Scientists also believe they have detected another form of Tritonian volcanism involving the slow flow of ice through the broad rifts that scar the moon’s pink surface.

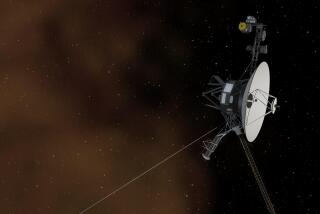

The next landmark--to employ a phrase which now seems quaintly terracentric--on Voyager’s long outward journey is likely to come about 12 years after the turn of the century. That is when scientists believe the craft will cross the heliopause, which marks the true boundary of our solar system. There, beyond the orbit of Pluto, the stream of hydrogen atoms and electrons constantly emitted by our sun--the so-called solar wind--ebbs and is overcome by the incoming particles of distant stars.

Scientists call what exists beyond that point the interstellar medium. Once, we might have called it the void of space. But now . . .