Cold Shoulder From a Brother Hurts : Filipinos See Us as Kin, Part of a Very Extended Family

- Share via

Ninety years ago the United States had conquered the Philippines and Rudyard Kipling urged us to “take up the White man’s burden . . . . “ But commentator Peter Finley Dunne’s caustic pundit, Mr. Dooley, drolly observed, “ ‘Tis not more thin two months since ye larned whether they were islands or canned goods.” Whether it was “the voice of God” that was intoning Manifest Destiny, or, in Richard Hofstadter’s phrase, “the carnal larynx of Theodore Roosevelt,” Americans embraced “benevolent assimilation” of the Philippines, forcing a highly articulate, mature nationalist movement to surrender its dream. The Filipinos were told by President William Howard Taft that henceforth they would be our “little brown brothers.”

After 50 years of colonial rule, followed by the Japanese invasion and the Bataan death march, Douglas MacArthur, Carlos Romulo, the Hukbalahap, Ramon Magsaysay, martial law and Imelda’s shoes, we in the United States still have only a hazy sense of the Philippine archipelago and our “special relationship” to it.

During the remarkable days of Ferdinand Marcos’ fall from power, when Corazon Aquino and Cardinal Jaime Sin mobilized non-violent “people power,” Americans briefly grew fascinated, turning history into a daily sitcom, a real-life version of the Passion Play with elements of “Macbeth” and “The Picture of Dorian Gray.” Then our attention drifted away until, a few days ago, Ferdinand Marcos died, having lived far longer than anyone would have diagnosed possible. (Benigno Aquino returned to Manila--and his assassination--in 1983 because, he told me, he was sure Ferdinand Marcos was dying of kidney failure.)

Vice President Dan Quayle was in Manila last week, urging that negotiations begin by December to resolve the fate of Clark Air Base and Subic Bay Naval Base, which are home to about 40,000 American servicemen and women and their dependents. These bases, the largest maintained by the United States abroad, are the second-largest employer in the Philippines. While Quayle was in Manila, the Communist New Peoples Army killed two American military technicians, a gruesome reminder of an insurgency that flourished under Marcos.

In a month, President Aquino will come to Washington on a state visit, an honor refused her by Ronald Reagan. George Bush, who foolishly toasted Marcos in 1981, saying, “We love your adherence to democratic principles--and to the democratic processes,” will try to make amends to Aquino and her nation.

To understand the Philippines, something we have never, as a nation, succeeded in doing, we must understand the centrality of kinship. It explains much, not only about how Philippine society itself functions, but also how Filipinos view their relationship to the United States.

The Filipino knows far more about his extended family than does his American counterpart. There is no way that a Filipino child can ever repay his obligation to his parents. Extending beyond the family are bonds that tie an individual to others from the same town and province, linguistic group and geographic area. Classmates and fellow alumni are halfway to kin. The patron-client relationships that link a tenant to a landlord, a ward politician to a regional office holder, a local store owner to a distributor in Manila define the reciprocal obligations of social hierarchies, joining the personalism of a pre-industrial land with the modern network of 20th-Century society.

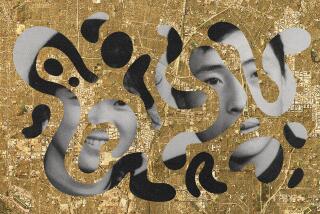

Whatever President Taft originally meant by “our little brown brothers,” the Filipinos have embraced the fictive kinship implicit in the phrase, translating imperialism from its distant condescension into a domesticated context. America justified imperialism as altruism, bestowing education and other social benefits as a way of assuaging a lingering guilt over the initial imperial decision. From the earliest days of the American interregnum, the political question was when the “little” Filipinos would be mature enough in their democracy to achieve their own independence.

It is the kinship bond that remains vitally important to them, if not to us. From the Filipinos’ perspective, they are still our kin, even though they reached their own maturity decades ago. They love us and hate us, just as a kid brother reacts to the older sibling. The Filipinos are now the second largest Asian-American community in the United States; Philippine society continues to be attracted to anything stateside.

But American society, which puts its parents into old-age homes, is uncomfortable with those emotional ties so vital to Filipinos. Even worse than when a big brother is angry at his young sibling is when he ignores him. That is what Americans have more or less done to the Filipinos for almost a century.