The Case of the Murdered Patriarch

- Share via

Only the night light illuminated David Werner when his daughter discovered him, a foot-long kitchen knife plunged in his neck, a pool of blood beneath his deathbed.

Deborah Ann Werner would tell police that she came home that April night to find their Mission Viejo townhouse helter-skelter--a toppled chair blocking the front door, lamps knocked down, the kitchen table upturned.

But even murder has a certain sensibility to it, and what Orange County Sheriff’s Department homicide detectives were seeing didn’t add up.

This appeared to be a violent burglary, yet nothing was stolen. Why did every room look like someone had struggled in it when the 72-year-old Werner clearly never left his bed? There was no sign of break-in, so how did the killer enter?

Then came the alibis, which unraveled like a cheap sweater. People weren’t where they said they were. And in less than a week after the April 15 slaying, Werner’s attorney said, two suspects admitted their involvement. One was the accused killer.

A case for Columbo this was not.

In all, four people have been charged in what prosecutors say was a plot to kill Werner for his money--an estate estimated by authorities at “several hundred thousand dollars.”

Sewn together from court records and interviews with attorneys and others, a story unfolds with a cast of characters who have little in common except unhappy childhoods.

* Deborah Ann Werner, a 40-year-old liquor store clerk whose former boss remembered her calling the victim “daddy,” is accused of master-minding her father’s killing. Werner and her two brothers, neither of whom are suspects, are the beneficiaries of his estate. She has steadfastly denied any role in the murder plot.

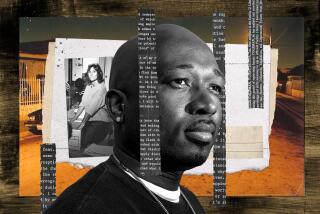

* Charles L. Clemmons, a 20-year-old Anaheim construction worker, is charged with smothering and stabbing Werner to make sure he was dead. Clemmons, who grew up in Los Angeles on welfare and bounced from job to job, allegedly received a $3,000 check from Deborah Werner after the killing.

* Carrie Mae Chidester, a 21-year-old telemarketer from Garden Grove and Clemmons’ former girlfriend, is also charged with murder.

* Cynthia Diebolt, 20, Deborah Werner’s daughter, was charged with solicitation for murder after she allegedly tried unsuccessfully to get two other men to kill her grandfather on behalf of her mother. Now expecting her second child, Diebolt is the only suspect not in jail.

It is unclear exactly what defense each suspect will offer as the trial unfolds. The three murder defendants are being tried together and have a preliminary hearing scheduled on Monday in South Orange County Municipal Court in Laguna Niguel. Diebolt will be tried separately.

But Werner has been seen by a psychiatrist “in order to help prepare her defense through psychological testing and interviews,” her attorney, Jack M. Earley, wrote in a court document.

And Earley and other attorneys involved in the case suggest that Werner’s defense may include tales of a daughter pushed to her limit in trying to care for an aging and alcoholic father who could be incredibly demanding, especially when he drank.

“This,” said one attorney involved in the case, “is really the sorriest, most pathetic cast of characters you will ever see. If you didn’t know they were accused of murder, you’d feel sorry for them.”

For, ultimately, killing the Werner patriarch for his money appeared to be utterly unnecessary.

Now fierce enemies who are kept apart during trips from jail to court, the suspects met through a series of intertwining relationships.

Charles Clemmons met Carrie Chidester at a bar. Diebolt was a friend of Chidester, who also worked at one time with Deborah Werner, a bookkeeper who also had done stints as a department store clerk.

Werner and Diebolt, the mother and daughter, had seen each other no more than half a dozen times in the 19 years since Werner and Cynthia’s father had divorced. But more than a year ago, the relationship was rekindled when Cynthia Diebolt called her mother before giving birth to her first child, Cheyenne.

The plot was first hatched last March, when Diebolt allegedly asked two men, who had been arrested with her earlier this year during a Westminster methamphetamine raid, to kill her grandfather, according to records filed by the Sheriff’s Department in West Orange County Municipal Court in Westminster.

She told them her grandfather was “worth some cash” and had a life insurance policy from which her mother would pay them for the murder, according to the court records.

The men, both of whom were awaiting trial on the drug charges, declined the offer, according to the records.

At about the same time, Clemmons was unemployed and spending a lot of time at a Garden Grove dance club called Faces, according to his lawyer, Donald G. Rubright. It was here that he met Chidester and they began dating.

Where Diebolt had failed, two sources close to the case said, her friend Chidester would succeed: she allegedly found Werner’s hired gun.

Court records, Sheriff’s Department statements and interviews with sources close to the case provided the following account of the hours before and after the killing.

David Werner, sometimes bedridden and cared for by his only daughter, Deborah, lay sleeping in his pajamas, having nodded off early for a Saturday night. Deborah Werner and her father had long been estranged, partly because her father did not like her husband. But after she got a divorce, the father-daughter relationship seemed to improve, friends said, and Deborah moved in to help her father, whose health was declining.

That night, Werner left the sliding glass doors unlocked at the El Moro Drive townhouse, then went outside. Clemmons entered, Werner was smothered with his pillow, then stabbed in the neck to ensure his death, said Lt. Richard J. Olson, a Sheriff’s Department spokesman.

The suspects attracted no attention in the quiet neighborhood.

Later that night--and apparently before police were summoned--Chidester, Clemmons and Werner gathered at a nearby 7-Eleven store, and a $3,000 check was given as payment for the killing, Olson said. (An additional $1,000 was promised but never delivered, he added.)

It was unclear exactly where Chidester and Werner were during the slaying, but Chidester’s attorney indicated that she was in the vicinity. “Once she realized it was really going to happen,” said lawyer Gary Pohlson, “she tried to talk them out of it, and wanted Deborah Werner to drive her back home.”

Werner returned to the home and called police about 1 a.m. Sunday. When they arrived at 1:17, she told them that her father was retiring for the evening when she left the home about 9 p.m. Saturday to pick up her friend, Chidester, in Huntington Beach. They returned to find the home ransacked, according to police reports.

But Chidester was not there when officers arrived. After she found the body, Werner told them, Chidester grabbed her and helped her into the living room. Then, Chidester “left to get something to drink” at a nearby convenience store “while she (Werner) called to get help,” Deputy Ray Cunningham wrote in his report of that interview.

Chidester did not return for nearly an hour.

By the following Saturday, after numerous interviews and alibi checks, first Clemmons, then Chidester, then Werner were arrested.

A fourth suspect was also arrested that day. But Bernadette Cemore, the deputy district attorney prosecuting the case, said she lacked enough evidence to charge him and he was released.

Five months later, Diebolt was arrested on a warrant charging her with the earlier solicitations for murder. Now pregnant with her second child, Diebolt was released from jail on $35,000 bail secured by her father’s Westminster townhouse, where she must stay by court order.

The other three defendants are being held without bail at e Orange County Jail as they await their preliminary hearing this week.

Investigators have not disclosed what, if any, physical evidence they have that might implicate the suspects. They have said inconsistencies in statements by the defendants led to their arrests.

One thing that the prosecution and defense attorneys say they agree on: Werner’s killing was more than a simple case of greed.

“Anybody who looks at it,” said Earley, Werner’s lawyer, “is going to have to look at family dynamics.”

None of the defendants had what could be considered stable childhoods. In fact, they were all either adopted or abandoned, at some point, by their birth parents.

According to information given to his lawyer, Rubright, Clemmons never knew his father; his mother would disappear for days, and at one point the state took custody of him and placed him in a succession of foster homes.

Chidester was given up by her birth mother, although Pohlson, her lawyer, declined to discuss that, saying her adoptive parents have stood by her since the arrest. Pohlson did say that his client had a weight problem and that her desperate need to be liked contributed to her unhappiness.

“Carrie wanted out of the whole thing, but she doesn’t assert herself. She doesn’t want people to dislike her, so she kept going along, hoping everyone would like her,” Pohlson said.

“Of course, that’s no excuse for murder, to get involved,” he added. But Chidester “never believed she was going to be involved in a murder. . . . She probably deluded herself that this was (not) going to happen.”

Because three generations are involved, the Werner family saga is perhaps the most painfully striking.

David Werner, born in Montana to Russian immigrant parents, had two sons with his late wife, Vera Mae, before they adopted an infant daughter they named Deborah.

Werner declined to be interviewed, and her lawyer declined to detail much of the woman’s past, which he said he did not know. His client told him that she had run away from home throughout her childhood, which was unpleasant.

“Her father was an alcoholic, and always was,” Earley said. “Her mother had some problems with alcoholism, too. That’s what I’m getting from Debbie.”

Cynthia Diebolt and her father, Jerome Diebolt, offered what they knew of Werner and her family through their attorney, Larry Bruce. Jerome Diebolt, who was once married to Deborah Werner, has known the family for 21 years.

According to their account, Werner told the Diebolts that she had been adopted but did not seem traumatized by that, Bruce said. She was close to her mother, removed from her father. “He was really more of a figurehead-type of father,” Bruce said.

Jerome Diebolt and Deborah Werner married May 4, 1968. Her parents refused to attend because Diebolt was Catholic; she was Jewish. Her only relative at the wedding was her brother, Joseph.

Deborah’s parents only came around five months after the wedding, when they learned that their daughter was pregnant. Fourteen months after Cynthia was born, Deborah wanted a divorce. When she got one, she took her daughter to live with Dave and Vera Mae Werner.

“Two weeks later,” Bruce said, turning away from the phone to double check with the Diebolts, “the grandfather calls (Jerome) and says, ‘You better come get Cynthia. Deborah’s gone.’ ”

Cynthia saw her mother rarely. By the time she was 15, she was getting in trouble. She barely attended Bolsa Grande High School in Garden Grove and then transferred to Lake Continuation School in Westminster, where she lasted six days. She was then reported as a runaway.

Cynthia evidently kept in touch with her grandparents, spending family weekends with them in Mexico.

Jerome Diebolt said Dave Werner was concerned that any contact at this late stage between Deborah and Cynthia would cause more harm than good to his granddaughter, who was having drug and truancy problems.

“He felt that it was genetic, that Deborah had passed on her problems to Cynthia,” Bruce said of the elder Werner. Mother and daughter were both abandoned by their mothers, ran away from home, got into trouble with the law, and were jailed and became mothers before they were 20.

Most of the neighbors in Werner’s Mission Viejo neighborhood said the patriarch seemed like a nice man who kept to himself. Others who knew him at a gymnasium in Orange described him similarly.

However, Robert Rubinstein, who lived across the street from Dave Werner and was also Deborah’s former boss, said there had been some bad blood between father and daughter before she moved into his Mission Viejo home during his divorce.

Rubinstein said Deborah Werner had been taken out of her father’s will until she moved in with him, less than a year before his murder.

“She called him daddy and was all sweetness,” Rubinstein recalled, “but she did not like him. She complained about him all the time. She wasn’t getting any money from him; she complained of having to support him.”

Rubinstein said Dave Werner drank heavily, getting out “his bottle of vodka at about 4:30 and packing it in for bed by 7:30 or 8. He was arrogant, too. A know-it-all.”

Though he said his client has denied any role in her father’s murder, Earley admits that their relationship was unhealthy.

David Werner, a retired stockbroker, was an ailing elderly man who could be “difficult to live with, especially when he drank.” He was a controlling father who so dominated Deborah’s life that he dictated his daughter’s visitors to their home and forbade her pursuing a relationship with her 20-year-old daughter, Earley said.

Earley said the elder Werner’s “infirmaries” forced his daughter to play nursemaid to a man who became “difficult” because he could not accept the limits of physical frailties such as heart disease.

“The only historian is Deborah because I don’t think we’re necessarily going to have cooperation from the rest of the Werner family. . . . Their perceptions of history are now going to be colored (with) her as the enemy,” Earley said, adding:

“But if you have the ‘Father Knows Best’ father and the perfect daughter, you’re not going to be in this position in the first place.”

“What you find in these cases is (that) a lot of people involved lose perspective with the problem,” Earley continued. “Family problems are like a sore tooth, and you are inclined with a toothache to want to take a pair of pliers and rip it out. But that’s not the best way.”

Before David Werner was cremated and his ashes scattered along the Long Beach shoreline, an autopsy was performed that provided an ironic footnote to his murder. He was a man dying of arteriosclerosis--hardening of the arteries.

“It would have been a miracle,” one attorney said, “if he’d lived through the end of the year.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.