Program Helps Group at Risk for AIDS

- Share via

NEW YORK — ARRIVE is a school that pays students $10 just to show up, but there are two requirements for admission: recent release from jail and a history of intravenous drug abuse.

The program works to develop a social-services network to help its students get back into society--and get what they need if they develop AIDS.

“The primary purpose of the program is to stop the transmission (of AIDS), but to do that you have to help people get their lives together,” said Dr. Harry K. Wexler, program director for ARRIVE--a loose acronym for AIDS Risk Reduction and Education for Former Intravenous Drug Abusers Entering Society.

Still, ARRIVE classes, which meet three nights a week, cover far more than AIDS awareness.

“I want us to quickly identify some of the things that stress us out,” Clinical Director Howard Josepher told a class of about 25 people, mostly men, who had gathered one night in a Lower Manhattan office building.

“Trying to deal with life now without the use of drugs,” responded one man with a graying goatee. “It has been so long.”

“Dealing with your children when they’re young,” another said, to a chorus of agreement.

“Dealing with a crack son,” a woman said.

In the early days, the cookies did not last through the evening; the organizers learned that some students had nothing else to eat. At least one showed up directly from jail, suitcase in hand.

ARRIVE has evolved in another way too. It has become something of an advocacy force for a high-risk population without a voice.

Since the start of 1988, intravenous drug users have accounted for more of the AIDS cases reported in the city than any other group. In an anonymous random sampling, about 35% of state prison inmates tested HIV-positive.

ARRIVE helps students draw up resumes and look for jobs, especially in drug and AIDS counseling. It gives out subway tokens and offers a 24-hour source of support, even to those who return to drugs.

“We have to deal with the fact that they’re going to experiment and they will be pulled back into old behaviors,” Josepher said.

Sometimes the streets win. Thirty-seven percent of those who entered ARRIVE did not graduate, figures from its first five groups of students show.

Some graduates get stipends to help others through the program. In August, one helper was shot to death in Harlem.

Many students left jail to find the streets changed--filled with younger faces and more violence revolving around crack.

“I’ve gotten a lot of feedback from our students that they feel like outsiders,” said Joseph Turner, an ARRIVE trainer. “Producing a lot of discomfort for people who’ve had a history of substance abuse will drive them back to the drug.”

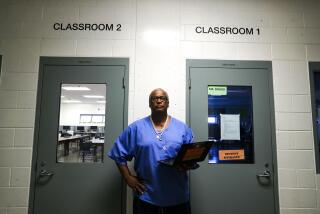

Those who stick it out are often people who have shown their strength before. Earl Ray got himself off speedballs, a mixture of heroin and cocaine, at age 24. At 30, he was ordered imprisoned for nine years for manslaughter; once inside, he sent himself back to school.

Now, he works for Narcotic and Drug Research Inc., which runs ARRIVE, going to prisons to recruit prospective students. He lives with a sister who is on crack. His brother is an intravenous drug user.

Jenny Melendez, 35, freed herself from a whirlpool of cocaine, alcohol and compulsive gambling.

“I used to gamble my food stamps,” she said. She joined ARRIVE with her husband, who is in a drug rehabilitation program. At home, she tells their six children, ages 4 months to 16 years, what she learns at ARRIVE.

ARRIVE is funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse, and the students are part of an experiment that will compare them to other ex-cons who get less treatment or no treatment at all. All told, a research subject can earn $280 for completing the program.

It is enough to bring people in but not enough to keep them, Wexler said. “People who don’t get motivated, who don’t get connected, they just leave.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.