The Saxons of Wabash: Together Once Again

- Share via

Ya gotta meet Joe Gold, Irving (Butter) Goldstein said, introducing a fit, silver-haired man in a red sweat shirt, the Joe Gold of Gold’s Gym. They had been classmates in East L.A. 50 or so years ago.

“He got us in shape,” Goldstein said, patting the midriff of his 330-pound body. “Now we’re on maintenance.” he laughed, enjoying his own joke.

Gold, Goldstein and other members of the old Wabash Saxons social-athletic club, were getting together, as they do once or twice a year, keeping alive friendships that were born in the 1930s and ‘40s when they were poor kids growing up in Boyle Heights.

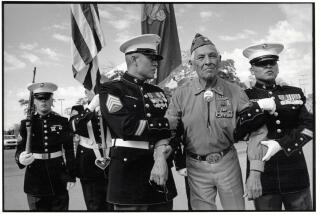

They had chosen Dec. 7, Pearl Harbor Day, for lunch at Salvatore’s restaurant on the edge of the old neighborhood. It was a date no one in this crowd was going to have trouble remembering, said Archie Eisenberg, the 66-year-old “Chairman of the Board.”

“Most of us graduated two months after Pearl Harbor,” explained Gene Resnikoff, 66, a retired Alpha Beta executive. “Out of 37 (who were Saxons then), 36 went into the service. One was out because he had a punctured eardrum. And we only lost one.”

Resnikoff stopped for a minute to think about Willie Goldberg who was killed in Germany on a volunteer scouting mission. Goldberg “wouldn’t hurt a fly,” Resnikoff recalled.

After World War II, everything changed. “We started getting married and stuff,” said Eisenberg, a retired Dad’s Root Beer supervisor. Still, 25 or 30 duly initiated Saxons keep in touch. And this lunch drew 75 men, including schoolmates who were members of other clubs and are now sort of unofficial Saxons.

The Wabash Saxons were kids of the Great Depression, street-wise youngsters who fought and played together at Wabash Playground. Many of them came from immigrant families, some with parents who grew up in the same towns in Eastern Europe.

“We were like brothers and sisters,” said Harry Pregerson, 66, judge of the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals. “Though we don’t see each other (often), we think about each other.”

Pregerson, a postman’s son who “wanted to be a lawyer all my life,” was the 1941 student body president at Roosevelt High School. As Goldstein recalled: “He was always the one whose father would call him, ‘Harry, come in and study.’ ”

Over a steak and spaghetti lunch, the men told once more stories that no doubt have been repeated again and again through the years.

Attorney Israel Levy was recalling how the boys used to go over to Santa Anita race track to see their Japanese-American classmates, who were detained there after the Pearl Harbor attack and waiting to be sent to internment camps. “We couldn’t go in and they couldn’t come out, so we would visit through the fence.”

John Peri, who has a South Bay beauty college, was remembering crap shoots on the playground. “That’s where I learned to multiply and divide and add.” And Arnie Klein, a businessman who, at 60, is one of the “youngsters,” was saying that in high school, as now, the boys looked out for another. “If they saw me smoking, they’d say, ‘What the hell are you doing?’ ”

At one table, Goldstein, 67, a meat salesman who includes his nickname on his business card, told how he came by it: When he was 12, he stopped by a neighborhood center and some of the boys said, “Come in, butterball. You’re a pledge (a Saxon). I was a heavy 240 pounds when I was in high school.” A football player, perhaps? “Stationary guard, that was me.”

Joe Gold, 67, who sold Gold’s Gym and now owns World Gym in Venice, also played football at Roosevelt. And “an old rickety garage” in front of his family’s house, which was two doors down from the Pregersons’, was the first Gold’s Gym. The boys called it “the dugout” and made weights out of cement and old flywheels, Gold said.

In those days, he was Sidney Gold, but his friend Seymour Rosen dubbed him “Joe.” Returning the favor, he began calling Rosen “Slasher,” another nickname that stuck. Slasher? Gold shrugged, “With a name like Seymour, wouldn’t you call him Slasher?”

Eisenberg, a rotund man in a plaid tam o’shanter, talked at the head table with Willie Harmatz, 58, who used to get kidded about his size when he and the others hung around Wabash Playground. But, even then, Harmatz was an athlete, an outstanding gymnast. At 110 pounds, he would go on to be a leading jockey of the ‘50s and ‘60s and winner of the 1959 Preakness Stakes with Royal Orbit.

The only black member of the gathering was Raphael Watson, 67, a retired McDonnell Douglas technician who was five times the city high-jump champion. “When I graduated from Roosevelt High,” he said, “there was a student body of 3,300 and 19 blacks, including seven members of my family.” It made no difference, Watson said--”We just loved one another.”

When the boys started out together, some as early as second grade, it was an innocent time, Eisenberg said. “We were here when it was a small town,” he explained. “And even though we were bad, we were angels compared with what they do today.” When he was 9, he sold newspapers at the 1932 Olympic Games at the Coliseum and was “so happy to make $1.50 for the day.”

Later, the boys used to stop at Carl’s, a drive-in not far from Salvatore’s, for hamburgers and Cokes. On New Year’s Eve, the city would block off Broadway, and they would sell confetti to those making whoopee.

“Then,” on New Year’s Day, he said, “we’d go to the Rose Parade and sell chairs. Then we’d go to the Rose Bowl and sell programs, and sneak into the game.”

On Friday and Saturday nights, they congregated in front of the Wabash drugstore, where Harmatz used to shine shoes. “We had a very good life.” Eisenberg said.

But Boyle Heights is no longer home to this bunch. After the war, they moved out--to the Valley, to Long Beach, to other states. One, Max Markowitz, went to New York and started Marco Fabrics of California. “I go to New York, he picks me up in his Rolls-Royce,” Resnikoff said while a “wish you were here” was being signed to be sent to Markowitz--a good man to keep in touch with.

As the party broke up, after almost three hours, everyone filed past the head table to shake hands with Harry Pregerson. That’s Judge Pregerson, you know. And he remembered everyone’s name. He even remembered the portrait of one man’s mother that used to hang over the piano in the family living room.

“It’s my life,” he said. “I’m tied in with these guys.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.