Politics, If Not Your Check, Is Likely to Be in the Mail : Government: One of the most important but often invisible political forces in America is the mailbox. It killed catastrophic health care.

- Share via

Late last year, Congress overwhelmingly repealed the Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act. The same elected officials who a year earlier had proclaimed the act a major legislative achievement rushed to say that its repeal was no less important.

What happened? Tons of mail demanding the law’s repeal were dumped on Capitol Hill.

But where did the opposition to the social program for seniors come from? After all, the legislation was the product of a careful compromise between the Reagan Administration and Democratic leaders and was supported by the largest senior-citizen groups in the country. If Congress could flip-flop on such a universally agreed upon program, what else might it flip-flop on?

The repeal of the Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act was the result of one of the most important but often invisible political forces in America--mailbox politics. One of the major political developments of the 1970s was the growth of special-interest groups who organized direct-mail campaigns around single issues. Although the type of person attracted to these organizations changed in the 1980s, their numbers and political clout grew. The direct-mail techniques honed by these activists undid catastrophic health care.

Nearly all the big stories during the ‘80s--from policy in Central America to abortion--shared something in common. Associated with them were large numbers of donors linked through mailing lists and, as a result, kept informed of new developments that usually required specific political responses. These communications were, in essence, an alternative press without the constraints of the regular media.

The power of such direct-mail organizations to mobilize citizens to action simply by depositing a message in a mailbox is decried by some, applauded by others. After the catastrophic-health-care fiasco, some legislators even urged that this form of political speech be regulated. But as in the case of television’s coverage of politics, criticism and calls for regulation are mostly intellectual hot air.

“Mail-order” political organizations are a sign of democratic strength. Viewpoints that may momentarily be in the minority or of little interest to the general public, but are strongly held by a diverse or scattered constituency, can be represented and promoted if their advocates can find each other. The only economically practical way to do this is through the mails.

This type of political activity has its drawbacks, of course. Leaders of mailbox organizations can exploit essentially unedited communications to manipulate followers. This is exactly what proponents of the Medicare Catastrophic Coverage Act accused the repeal groups of doing. Such political manipulation and demagoguery, to be sure, occur in all political settings. But with direct mail, there are few, if any, of the usual checks and balances associated with political advocacy.

Another drawback of mail-order politics is its tendency to focus on a special interest to the exclusion of all legitimate competing interests. But everyone looks out after their own interests first. The problem is that decision-makers, who must balance competing interests, are afraid to talk back to the direct-mail organizations, as they apparently were in the case of catastrophic-health-care legislation.

The benefits of advocating through the mails are substantial. Direct-mail organizations are meaningful and legitimate political outlets for a large and diverse society. They are a detour around the institutional inertia of the established political order; they facilitate the introduction of important new political issues into the political arena. Many senior citizens who supported repeal of catastrophic health care, for example, felt betrayed by the established seniors’ group because it supported a new tax. They recognized the need to form a new organization to represent their viewpoint. The mails gave them their opportunity.

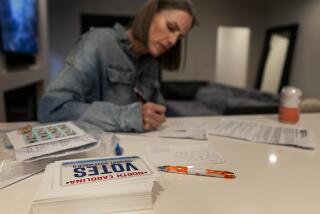

Thus, average Americans can sit at home and let the political process come to them in the form of “offers” to become involved with new causes and issues. He or she can select what issues or groups to support with much greater flexibility--and often with greater effect--than either can choose their representative. As with mail-order merchandise, stay-at-home letter readers can draft their own mail-order political platform and tailor their own political campaign. They know where to recruit: from lists of people who have supported other causes.

This networking of people through the mails is how the Reagan revolution was able to spread. The opposition to Judge Robert H. Bork’s nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court was another example of the same phenomenon. Politicians who switched their allegiances did so because the cumulative weight of active public opinion shifted.

The passing of a political issue can also be determined, in one sense, by monitoring the mails: When the targets of the tens of millions of direct-mail appeals “order” fewer of the “offers” found in their daily mail. It is hard to create a sense of urgency when there isn’t any, or maintain collective, cooperative efforts when interests diverge. This is one of the safety valves in the direct-mail system. Another is the existence of competing offers, and the capacity of people to know when their efforts are being wasted.

The main beneficiaries of “mail-order politics,” as with most large-scale political activities in America, is the middle class. There is something inherently democratic about a movement composed of hundreds of thousands (even millions) of individual supporters, which is precisely the case with most mailbox organizations and not with most political-action committees. The main losers, as usual, are the less affluent, largely because they do not have any alternative means of being heard. And since the poor are less settled, less established and preoccupied with more basic concerns, they remain underrepresented.

The techniques of mailbox organizations do not exist in the political desert. Direct mail is now an integral part of most political activity, whether of candidate, party or political action committee. Neither is the power and influence of television any less. Actually, many think of direct mail as “poor man’s television.” But as the TV-evangelist experience has shown, it is the checks in the mail, which usually come in response to direct-mail appeals reinforced by television, that pay the television bills.

The two media--television and the mails--combined create the most power, but only through the mails can carefully targeted, pre-selected messages be sent. Indeed, the best place to look for the new issues and groups that will dominate the 1990s will be your mailbox. And if you’re lucky, you’ll find messages from the group or groups who represent your views. If you don’t see what you like, why not create your own?

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.