Taking ‘Wilding’ to the Stage : Keith Antar Mason combines Central Park incident with mythology

- Share via

Almost every night for the past month, a group of 31 young men and women, most of them black, have gathered in a chilly, empty industrial building at the 18th Street Arts Complex in Santa Monica. They’re rehearsing Keith Antar Mason’s newest performance work, “Prometheus on a Black Landscape: The Core,” which uses last April’s violent “wilding” rampage in New York’s Central Park as a jumping-off point to explore historical and mythic roots of black male aggressions.

It opens Thursday at Highways, also at the 18th Street Arts Complex, for a two-weekend run and is the third offering in the 10-week “Sex, God and Politics Performance Festival.”

“Prometheus” blends the characters of the wilding incident with figures from Greek mythology and the Efa religion of West Africa, first communicated to Mason by his grandmother in his native St. Louis.

It integrates the audience in the action, opening with a house party thrown by the “Ashanti Bloods” street gang where members of the audience are guests. Mason’s work will continue to engage the audience at the intermission, when a mock art-gallery opening is staged--”a chance to facilitate dialogue” between cast and audience about the issues of the play. One of the final scenes of the piece takes place in a courtroom.

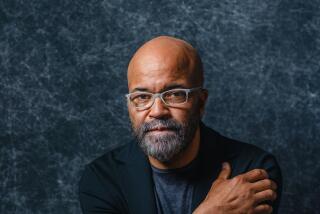

Mason, 33, is the writer-producer-director. An award-winning writer whose plays, poems and performance pieces have been mounted all over the country, his works will soon be aired on public radio and television. He holds two degrees from St. Louis’ Webster College, where he taught and performed in the late 1970s. He moved here in 1985 with a few performance art colleagues who called themselves the Hittites.

Mason says he was “overwhelmed” by the “media bombardment of racist allegations” after the Central Park incident. “It was destroying my humanity,” he says of the coverage. Mason’s performance piece, in which the alleged rape of a jogger is performed as a dance choreographed by Rika Ohara, contains the repeated incantation “Something black has got to die.”

The incident that inspired Mason’s work occurred on the evening of April 19, when a group of young black men from a Harlem housing project swept through Central Park and allegedly beat and robbed two men and raped a woman jogger, leaving her for dead.

The woman, a 28-year-old employee of a major investment bank, was found hours after the attack. She remained in a coma for nearly two weeks. “It was fun,” one of the suspects reportedly said; others allegedly whistled at policewomen and sang a popular rap song while in a precinct holding pen, apparently showing no remorse.

While physicians had initially predicted severe brain damage if the victim survived, she has recovered almost completely. She has returned to her job, but still has no memory of the incident. Meanwhile, six of her attackers are scheduled to be tried in April on charges changing from rape and robbery to attempted murder.

Sections of Mason’s work attempt to let the audience in simultaneously on the nightmare of the suspected rapist and the coma of the jogger, a dream space in which the two, both cast as victims, confront their mutual fear and frustration.

“There’s a scenario in the American psyche,” says Mason, “that black men are crazy and they’re going to act on their anger. This is a myth, like the idea that black men see the whole feminist agenda as an enemy. We’re up against media-induced divisiveness. Add to that the xenophobic race relations in America and you get an explosive event like the ‘wilding’ incident.”

The very nickname of the event, derived from the title of rapper Tone Loc’s “Wild Thing,” infuriates Mason, who believes “wilding” is “a misunderstanding of the term working , a rite of passage (among black males) to go out and intimidate to feel powerful.

“Rap music is not the cause of the incident,” he says. “It’s the documentation of a modern black cultural experience in America. It’s a social document.”

Mason has written the lyrics for a rap that introduces his characters and their situation, a number scored by 23-year-old composer Keith Kaplan. The rest of Kaplan’s music for “Prometheus” owes more to Schoenberg, Stravinsky and Philip Glass than to rappers like Tone Loc. The score has overtones reminiscent of Greece and North Africa and will also include live African drumming by members of the CalArts African Drum Ensemble.

“I am guilty of confusing art, religion and politics,” says Mason. “I confess I am Prometheus; I stole his fire. I’m on the front line in this issue. When you present these horrific images of black men, that implodes inside me. It does affect my self-esteem.

“As hokey as it sounds, it’s a morality play,” Mason says. “The spiritual entities in it set up a courtroom drama; the judge is a vulture. How many black guys get to play Justice as a vulture? I’m not trying to preach or convert. I’m trying to self-examine, and explore what life in the late 20th Century means.”

Mason has launched 12 previous productions in communities all over Los Angeles under Hittite auspices, including the controversial “MaskMen and the Blue Drum Incident,” a 1987 presentation that approached the Bernhard Goetz incident from a black perspective. In late 1988 he offered “For Black Boys Who Have Considered Homicide When the Streets Were Too Much,” the male response to Ntozake Shange’s choreo-poem “For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide When the Rainbow Is Enuf.”

“I’m tired of proving myself all the time,” Mason says. “There has to be some place where I can just go and be myself. To me, it is being the artist that I am, defining the world in my terms: the self-discovery process.

“I’m tired. In the African-American community, the things that promote self-esteem--the black church, black businessmen--are not functioning. The generational links are disintegrating. I feel like I belong to a generation of black men the likes of which has never been seen on the face of the Earth. We accept the responsibility of healing the world and participating fully in all the contradictions the world has in store for us.

“We’ve synthesized all the information between King and Malcolm X, and somehow we were made whole. We new black artists in commercial film and performance art are articulate and well-informed. We--Eddie Murphy, Spike Lee, Bill T. Jones, John Pickett--have the power to create the image for ourselves; nothing can hold us back. Unless we are completely able to liberate the images of ourselves for ourselves in the arts, our culture won’t survive.”

In “Prometheus,” Mason has created many images. The actors chant as well as dance; some of the multiracial cast appears only on video, and some characters are played simultaneously by several actors.

The role of Medusa will be taken on video by poet Wanda Coleman, who says she plays “the other side of the physical dancer played by Meri Danqua. I’m sort of the metaphor for Mother Africa.”

Coleman, a native of Los Angeles who says she was a rape victim, calls her role “a resonance, part of the historical context. Most rapes are intra-racial; it’s very seldom that it’s cross-racial. Keith is tying the history of black Americans to the incident in Central Park. This incident is really important to the black community because of all the things that reverberate. When an incident involving a person of color takes place, it’s always presented with no context. Black lives, even today, do not have the same value that white lives have, economically or morally . . . .

“Keith is clear on the cultural context. He’s livid with rage. He’s so articulate on how the culture abuses the black male. I regard his energy as the strongest black male energy in L.A.”

Mason and his actors have their craft and their comradeship as tools in the struggle for a positive black identity. The cast of seven women and 24 men, all professional performers, has put in months of work with little promise of financial reward after the six-performance run.

“I’m paying them attention,” declares Mason. “I want my actors to have a personal commitment to their pain. Brothers do rape. We have to deal with that.”

Mason has shifted the locale of the “wilding” incident to Los Angeles, intent on expressing poetic rather than literal truth. “The piece may not have a factual basis, but it has an underlying truth that can’t be denied,” he says. “I’m creating a mythical blues piece that will confront the audience as well as the cast about the issues of racism and sexism. Being black and a man, in America, feels like being hung between the heavens and the Earth,” observes Mason, who re-creates this image by suspending the actor who plays Prometheus from the ceiling.

“The piece is a tragedy. The things we’re not supposed to talk about are what I want to make art about . . . men who did a violent act against humanity.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.