Canada’s Sensible Approach : Health Care: While U.S. politicians recoil at the mention of national insurance, our neighbors to the north are becoming the envy of many Americans.

- Share via

Forty-eight percent of the American people fear that they could not afford good medical care if they became critically ill, according to one poll. Nine out of 10 believe that the health-care system needs fundamental change. Two-thirds tend to favor a national health-insurance system of the sort enjoyed by Canadians.

The politicians, however, are not impressed. As a key California congressman observed, “It’s hopeless to get a comprehensive (health) plan passed in the United States, politics being what it is.”

Although Congress uses the budget squeeze to justify inaction, the problem basically isn’t money. It’s the failure of the American health-care system to give us our money’s worth.

Americans spend more for medical care than any people on Earth--more than $600 billion a year, which figures out to $2,500 per person, or more than 11% of the gross national product. Relative to population, we spend 40% more than the Canadians, 61% more than the Swedes, with their supposedly bloated welfare state, 85% more than the French and 130% more than the Japanese.

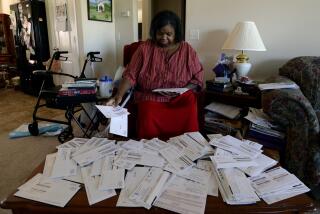

Yet, whereas these countries provide medical care for all their citizens, 37 million Americans have no health insurance at all. And our enormous outlay notwithstanding, life expectancy in this country is lower than in many other modern societies. In infant mortality we rank 22nd in the world, behind Canada, Japan, Western Europe and even some Third World countries.

Meanwhile, medical costs--and health-insurance premiums for both employers and employees--continue to soar.

The existing system, with its emphasis on health insurance provided through employers, supplemented by government-supported programs for the poor, has unfortunate side effects.

Welfare recipients have a disincentive to seek work because they will lose Medicaid coverage.

Job mobility is discouraged because employers are reluctant to take on new workers with ailments or disabilities that would trigger increases in company-paid insurance premiums.

Wages are depressed as employers try to offset rising health-insurance premiums.

Employers’ enormous medical insurance costs act as a tax on exports, reducing the ability of U.S. companies to compete with producers in countries where health care is financed through national insurance.

It is little wonder that the Canadian system is attracting interest. That system isn’t perfect. But Canadians spend much less than we do on medical care, live longer and score better in such indicators as infant mortality and heart-disease fatalities.

The Canadian plan guarantees comprehensive medical and hospital coverage to everybody in the country. People choose their own doctors. There are no deductibles and no extra charges beyond the prescribed rates and fees, which are set in negotiations between the medical profession and provincial governments.

Canadian doctors might prefer the freer-wheeling U.S. system. But their incomes compare well with other professionals in Canada--and there has been no big flight of physicians to the United States.

U.S. politicians, however, recoil from national health insurance because they fear it would cost more--and are convinced that the voters share President Bush’s well-known aversion to new taxes. To the extent that they address the issue at all, they incline toward legislation requiring all employers either to provide adequate medical insurance or pay taxes for a government safety-net program.

Even this approach lacks sufficient support, which is just as well. It would penalize U.S. global competitiveness even more than now and, in the long run, would take more money out of our pockets than would national health insurance as companies passed on their higher costs to consumers.

The Canadian approach makes much more sense--especially if combined with reform of U.S. liability laws, which force doctors to pay big malpractice insurance premiums and encourage them to order unnecessary tests.

With a universal system, we would no longer need separate taxpayer-supported systems for the poor, the elderly, veterans and the like, nor would there be much need for private health insurance.

Savings in administrative costs would help, too. About 8.5% of health spending in this country goes for administration, compared with only 2.5% in Canada. The difference lies in the enormous paper work generated by hundreds, even thousands of different medical plans here, compared with Canada’s single basic system.

The biggest obstacle to decent medical care in America is not the cost in dollars, but the resistance of entrenched interests in the medical and insurance industries to fundamental change in a system that costs too much and delivers too little.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.