Test Gauges Skills of Oregon’s Work Force : Literacy: A new state agency is working to find ways to make residents more competitive in the job market.

- Share via

SALEM, Ore. — In what could be a model for a future nationwide effort, the state of Oregon is quizzing people to learn their work skills--and it’s willing to pay the guinea pigs.

Researchers trying to gauge the talents of the Oregon work force have fanned out across the state to ask people about their basic abilities--such as whether they can understand a simple newspaper report, calculate the cheapest brand of peanut butter or use a bus schedule.

As an incentive to take the 80-minute test, people are paid $15 if they complete the questions.

The survey is part of an effort by the new Oregon Progress Board to set measurable goals for making the state’s work force more competitive. The board, created last year to plan long-term economic development, wants to know what employees can do now before setting targets for the future.

A similar effort has been started in Mississippi, but the Oregon survey is further along, according to officials of Educational Testing Service, the Princeton, N.J., company that wrote the quiz.

Doug Rhodes, field director of literacy assessment for ETS, said the Oregon program may produce valuable lessons for a 1992 survey by the U.S. Department of Education.

“It will follow very similar lines and objectives as the Oregon one,” Rhodes said of the federal test. “We look at the Oregon experience as a pilot effort.”

Rhodes said the federal agency has hired ETS--best known for administering the Scholastic Aptitude Test given to high school students--to question 13,000 to 14,000 adults about their work skills. He said the company is writing the test now.

Laura Neidhart, president of a Portland company hired by the state to conduct the Oregon research, said most people have been willing to take the survey, providing they can find the necessary time--an hour to answer the questions and another 20 minutes to provide demographic data such as age and education.

“We’re having a little bit of trouble with people not having enough time to complete it,” said Neidhart, president of Bardsley & Neidhart.

Neidhart’s company hopes by the end of June to quiz 2,000 randomly selected Oregonians between 16 and 65, and then compile the data to create a comprehensive picture of what the state’s workers can do on the job.

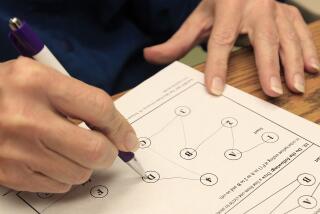

Once they agree to take the test, subjects face about 30 questions or problems divided into three broad categories: prose literacy, document literacy and quantitative literacy. Essentially, the first category deals with how well people can understand written material, the second with charts and graphs, the third with mathematical calculations.

State officials said they cannot release the full text of the test, but they did provide United Press International with questions from a similar ETS test the U.S. Department of Education used several years ago to quiz 21- to 25-year-olds. In fact, some of the questions are on both tests, although officials would not say which ones.

The questions in prose literacy range from interpreting an Emily Dickinson poem to reading a newspaper story about a long-distance swim and simply circling the sentence that describes what the swimmer ate.

Document literacy involves reading a simple chart, finding figures on a pay stub or using a bus schedule.

Questions in the final category--quantitative literacy--range from simple addition to figuring per-ounce prices for two hypothetical jars of peanut butter.

Duncan Wyse, executive director of the Progress Board, said the survey is designed to test “real-world problems.”

“When we say literacy, it’s not just writing your name.” It’s more the ability to use documents you’d find at work, said Wyse.

State officials were originally worried that people might be suspicious of someone knocking on their door and asking them about their abilities. As a result, those leery of the test are given the telephone number of the Progress Board, but staff members say few people have called.

Stevie Remington, executive director of the Oregon branch of the American Civil Liberties Union, said her group has no objections to such tests so long as the results are not identified by individual. Progress Board officials say subjects are not even asked their names.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.