MOVIE REVIEW : Small Town Explodes as Two Families ‘Feud’

- Share via

Why do men war with and kill each other? Great ideals? Land, gold, beautiful women? In his 1983 comic novel, “The Feud,” Thomas Berger suggests that we fight and die because of stupidity and stubbornness, geography and lies.

Berger’s story--about a daffily escalating small-town vendetta, engendered by trifles and proceeding to catastrophes--is great movie material. But the film that’s been made from it, Bill D’Elia’s “The Feud” (at the Fine Arts), shows little imagination, less intensity. It preserves much of Berger’s dialogue and plot, but little of the Swiss-watch precision and comic ruthlessness that animates it.

The basic story is a wry holocaust, set in the era of Bonnie and Clyde, in which two families, the Bullards of Millville and the Beelers of nearby Hornbeck, become embroiled in hostilities that claim two lives. The cause: an inane argument over paint remover and an unlit stogie in Bullard’s hardware store.

The novel is about small-town dopes with frontier dreams. The combatants are frustrated little men, nasty teen-age punks, hothead bullies leading dull lives: all of whom explode over nothing. D’Elia’s film, fast-forwarded into the 1950s--for no perceivable reason except the lure of a rock ‘n roll period score--loses that desperate ‘30s edge, the sense of lawlessness and hard times that fuels the feud. It becomes an urbanized sitcom in which the dopes are stripped of their cosmic obsessions.

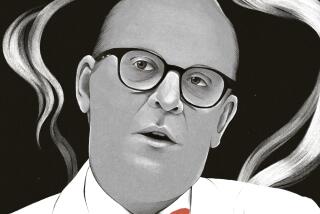

Except one. As Cousin Reverton Bullard--an alleged railroad detective who carries around a starter’s pistol to terrify would-be assailants--Rene Auberjonois has a great face that’s a cross between a mad ferret, a shabby Puritan lay minister and one of cartoonist Charles Addams’ evil bald little men. He’s the ultimate outsider, a knee-jerk bigot with a hair-trigger temper and, within minutes of the credits, he’s pulled his gun on the equally foul-tempered Dolf Beeler (Ron McLarty), uncorking a donnybrook that rolls along like a Laurel and Hardy destruction derby. But D’Elia never develops the visual grace to match Berger’s dead-on dialogue. And, except for Auberjonois--and Ron Vanderberry as the unspeakable teen-age snot, Junior Bullard--he hasn’t cast well, either.

Stanley Tucci, an expert comic actor, is too urban and snappy for the beefy, lecher-bully police chief, Harvey Yelton; Gale Mayron too Brooklynesque tarty for sister Bernice Beeler; Lynne Killmeyer too old for 13-year-old sexpot Eva Bullard; Scott Allegrucci too sharp for her football lineman beau, Tony Beeler.

Perhaps D’Elia can’t keep a secret. He reveals, as they happen, the culprits behind the Bullard hardware store fire and Beeler car bombing--destroying much of the story’s suspense and irony. He’s lost the dark passion and longing of Eva and Tony’s Juliet and Romeo pursuit and encouraged Joe Grifasi, as Bud Bullard, to a ridiculous crazy-ape breakdown.

The book is by someone who really understands small towns; the movie seems to have been directed by an urban kibitzer who finds them coy, silly and grotesque. But D’Elia deserves every credit for finding this book and bringing it to the screen--even if we might wish that Arthur Penn or the Coen Brothers had found it first.

“The Feud” (rated R for sex, language and violence) has something most movies don’t: a good story, if not always a well told one. Stupidity, as we learn here, is eternal, passion only temporary.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.