Bejart Pyramid Scheme Collapses in Fiscal Flop : Culture: Egypt’s attempts to boost tourist revenues using the arts fail again.

- Share via

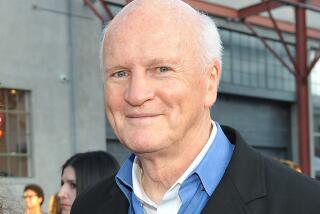

CAIRO — Choreographer Maurice Bejart stood at the Pyramids and imagined a tableau of dancers swooning to the rhythms of the East, framed only by the starry night sky, the tombs of ancient kings and, like an eerie, whirling backdrop, the Egyptian desert.

Back home in Switzerland, he set about creating a mystic, sensual ballet to give movement to the splendor of ancient Egypt and the modern Islamic faith.

Belgian promoter Michel Reculez contracted with an Egyptian company to construct the stage. Costumes and set backdrops were flown in. Sophisticated new lighting equipment was leased. Tickets were sold to travelers from all over Europe for what was to be one of the cultural events of the decade here: the premiere of Bejart’s “Pyramid” on the Pyramids Plateau of Giza.

The Egyptians had visions of their own, however: Customs wanted a 20% duty on the imported equipment. Tax authorities wanted $50,000 for each of the eight scheduled performances as an advance. The antiquities organization wanted royalties of $3,800 per performance, plus another $11,300 deposit, and demanded 150 free tickets each night. Then, two days before last month’s premiere, the contractor announced the price for building the stage was not $211,000, as promoter Reculez believed, but $566,000.

In the subsequent dispute, 200 police officers blocked access to the site and the performance was called off.

Reculez flew back to Brussels and declared bankruptcy. A visibly shaken Bejart announced that the ballet would go on, but only at Cairo’s downtown opera house, not at the Pyramids. Angry ticket-holders unsuccessfully demanded their money back. The lighting company directors hired an Egyptian lawyer to try to get their $600,000 worth of equipment out of the country.

“It’s like Kafka--no, it’s worse than Kafka. It’s state robbery,” declared one Belgian government official who tried to intervene.

The fiasco was but the latest setback in Egypt’s attempts to capitalize on its legendary archaeological treasures as modern cultural institutions. Seeking to boost tourist revenues and bring new life to the ancient monuments, Egyptian promoters have sponsored concerts at the Pyramids and lavish productions of the opera “Aida” at Luxor and Giza, and they have attempted to organize a music festival at temples up and down the Nile.

Although the events have been enthusiastically received in the arts community, most have been fiscal flops, resulting in months of finger-pointing, lawsuits and recriminations.

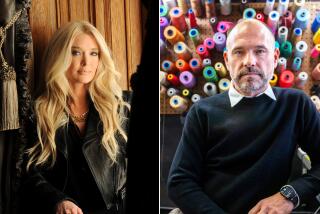

“Egypt is a great lure, but we’ve had so many of these disasters,” complained Magda Saleh, former director of Cairo’s opera house. “The government is behaving as if, no matter what happens, we want our pound of flesh. Well, they got their pound of flesh, but the (promoter), for whatever reason, got ruined. . . . There’s quite a history of this sort of thing, and it’s a pity. It’s like killing the goose that lays the golden egg.”

Well-known Egyptian opera singer Hassan Kamy, who produced “Aida” at the Pyramids in 1987, complained in a special column: “It is obvious now that we will never be capable of having such a big cultural event in our beautiful country unless we get rid of all this bureaucracy and realize the enormous loss we have sustained by killing the Bejart project.”

Kamy’s interest was rekindled by more than the publicity over the Bejart production and by his own memories of haggling with tax and customs officials over “Aida,” which eventually drew an audience of 27,000. After imposing customs duties on the Bejart production, authorities checked their records and determined that no similar duties had been assessed to Kamy in 1987. Three weeks ago, he got a letter demanding $106,000.

Egyptian government officials admit that productions at archaeological sites so far have been money losers, but blame the losses on Western producers who don’t bother to learn how to work the system in Egypt.

“People expect to do things as they do in Berlin or Frankfurt; they expect everything to go a la West, and then they make enormous mistakes,” Tarek Ali Hassan, current director of the Cairo Opera, complained in an interview Thursday.

“I reject out of hand these claims that the system is inefficient, the system is unfair. It is not. Somebody has not done their homework properly. A lot of planning is needed--a lot of groundwork. As it happens, Westerners are used to the normal channels, and the normal channels do not apply here.”

Some in the Egyptian arts community privately say that Reculez, a travel company owner with no previous experience producing a major cultural event, should have familiarized himself better with the Egyptian bureaucracy before launching so large an undertaking.

But Reculez says he could not have anticipated the last-minute demand by the contractor building the stage that effectively tripled the price. The contractor, who has declined interviews, has told the Egyptian courts that he had informed Reculez from the beginning that the price was to be charged in dollars, not Egyptian pounds--and thus Reculez should have anticipated the figure.

The dispute was further complicated when the subcontractor supplying the wood for the stage suddenly demanded an extra $350,000 in case it was decided to make the stage permanent rather than dismantle it after the performance. Reculez put up a check to cover the demand as a deposit, pending resolution of the dispute after the performances. The contractor attempted to cash it, and when it bounced, the Egyptian authorities seized not only the theater, but also the hundreds of thousands of dollars’ worth of leased electronic equipment that was already installed.

Reculez, his own house in Brussels mortgaged to cover the advance costs, went home having spent $500,000, without a cent of revenue to show for it. Bejart’s Ballet Lausanne performed at the opera house free of charge--confident, perhaps, that the production will earn money later at European performances.

“I lost everything,” Reculez said in an interview. “It’s a very big scandal, you know. The problem in Egypt is that nothing is easy. Nothing, nothing, nothing.

“Before, you receive with a smile all authorization. ‘Yes, come, come.’ After that, everybody-- everybody --asks to be paid. In advance. For tax. For customs. For everything you have to pay in advance, and when there is a problem, you don’t find anyone able to find a solution. You find nothing.”

Bejart, meanwhile, has declined to comment publicly on the matter, calling it a business dispute between the promoter and the contractor. At a news conference last week, he said he was glad at least to be able to open the production at the opera house.

“The main purpose was to give an Egyptian performance to the Egyptian public, and we find a lot of the possibilities to make (it happen),” he said. “We want to give our view of this wonderful civilization, to give it to the world, and mainly to the Egyptians.”

He added: “I don’t like to lose. So maybe I lose the Pyramids, I lose the desert, I lose everything, but the public’s not going to lose.”

But Kamy said Bejart privately was “in deep pain,” and Kamy himself refused to attend any of the seven performances at the opera, which concluded last week.

“Of course, one-third of something is better than three-thirds of nothing,” he said. “But as an artist, I feel wounded like him. I see what’s in his face, I hear his voice. I did not go. I did not want to see it. I did not want to see one-third of the thing.”

Though the government remains committed to producing cultural events at Egypt’s historic sites, Hassan said, the Bejart performance was a success even within the confines of the opera house--in part, he said, because it was among the first theatrical works produced in Cairo that forced Egyptians to examine and question their identity as the heirs of both Ramses and Mohammed, Napoleon and Alexander.

In the days after the performances, columnists began asking about Bejart’s mystic view of Islam and wondering whether it did not lean more toward his own Shiism, rather than the Sunni Islam that most Egyptians adhere to. Some criticized his depiction of the beloved Egyptian diva, Om Koulthoum, as “grotesque.” But despite scanty costumes and veiled Muslim women in punk sunglasses, there were none of the usual complaints from Islamic fundamentalist quarters that frequently occur at Egyptian cultural events.

“What has happened is this production, with its richness and its greatness, has set a lot of people thinking--it has created healthy controversies,” Hassan said. “People were transformed, as if by magic, when they left. People that don’t know each other were talking to each other, people were set wondering, questioning. This, I think, was one of the greatest gains of the experience, whatever else happened.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.