THE SUMMIT AFTERMATH : White House Says German Unification Will Be Incremental : Diplomacy: There will be no giant step, officials say. Bush speaks by phone with Kohl and Thatcher.

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Despite the optimistic glow left by President Bush’s summit meetings with Soviet President Mikhail S. Gorbachev, the White House said Monday that one of the most pressing issues--German unification--will be resolved only incrementally, rather than in one giant step.

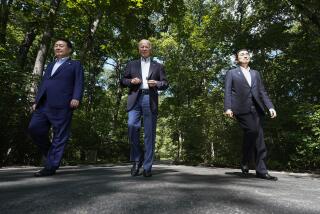

Shortly after saying farewell to Gorbachev on Sunday, Bush spoke by telephone with West German Chancellor Helmut Kohl and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher on the four days of talks, White House Press Secretary Marlin Fitzwater said.

Reflecting the quickened pace of post-summit diplomatic activity on Bush’s schedule this week, Kohl will have dinner with the President at the White House on Friday.

“He told the leaders . . . there were no breakthroughs, but he feels we have a better understanding of our positions,” Fitzwater said of the President.

In addition, the White House announced that for the first time the prime minister of East Germany will visit the White House. The official, Lothar de Maiziere, the first non-Communist to lead the nation, is scheduled to see Bush at lunch next Monday.

Bush reported briefly on the summit to his Cabinet, saying during a picture-taking session before the meeting began: “I am pleased with the results. . . . There are some problems. We never said there wouldn’t be. We had a chance to describe the problems.”

But even though the flurry of activity suggested movement, the pressing question of whether a newly unified Germany will be a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization remained very much up in the air. The uncertainty persists despite Gorbachev’s surprise acceptance of Bush’s proposal that the superpowers should be guided by a 1975 agreement, reached in Helsinki, that every nation has the right to decide to which alliances it will belong.

White House officials said that Gorbachev’s readiness to accept this formula during their meeting Thursday afternoon, the only time they talked substantively about Germany, caught the Soviet leader’s own delegation by surprise.

When Gorbachev said that he agreed with Bush’s view, members of his delegation “blanched,” one White House official said.

The Soviet leader was said to have then turned to his foreign minister, Eduard A. Shevardnadze, and suggested that he pursue the discussion about Germany with Secretary of State James A. Baker III.

But Shevardnadze at first showed some reluctance, telling Gorbachev, “I don’t see any reason to, Mr. President,” one Administration official said.

The official, speaking on condition of anonymity, likened the seeming disarray within the Soviet delegation on the German question to that which occurred among then-President Ronald Reagan and his aides during the Reykjavik summit conference in 1986. At that time, Reagan and Gorbachev went so far as to discuss banning all ballistic missiles and, at one point, banning all nuclear weapons--steps that ran counter to U.S. policy.

Such incidents, another official said, are symbolic of the problems that Gorbachev faces within his own political, foreign policy and military establishments.

“He’s got to get things from us to help him assure his country this is a reasonable way to go,” the official said.

Until Gorbachev suggested in the Thursday meeting that there are conditions under which he could accept a NATO role for a united Germany, he had strenuously objected to any such German connection with the Western military alliance, out of concern that the alliance would become all the more powerful while retaining its anti-Soviet approach of the Cold War years.

Indeed, Shevardnadze, in Copenhagen, Denmark, for a meeting today of the 35-nation human rights conference, said that rather than let Germans alone decide, the issue should be settled in the “two-plus-four” talks on unification among the two Germanys and the four major victorious Allies of World War II, the United States, the Soviet Union, France and Britain.

Fitzwater, reflecting the feeling in the White House that the German question will continue to drag on for some time, said that the matter “is clearly going to be resolved over a period of time in an incremental kind of debate and consideration. It’s not going to be resolved in any dramatic announcement either from us or from the Soviet Union unilaterally.”

Administration officials put little stock in Gorbachev’s threat to slow down Jewish emigration, saying that he was “posturing” for his Arab allies. On Sunday, the Soviet president said at a White House news conference that Moscow may suspend its relaxed emigration policy and once again prevent Jews from leaving the country unless Israel provides guarantees that Soviet emigres will not be settled in the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip.

The officials said that the first Bush heard of the West Bank issue from Gorbachev--and the seeming threat to throttle back Jewish emigration--was when it arose at the news conference.

“It never came up in private,” one senior official said, adding: “Our private feeling is he was posturing for his Arab friends. Nothing leads us to believe he wants to do that.”

Syria is the Soviet Union’s closest ally in the Middle East, and the Soviets are also strong supporters of the Palestine Liberation Organization.

Officials also reported that the final round of talks between the two presidents produced no sign of specific movement on a number of regional issues and that the Soviets balked at issuing a joint statement on Afghanistan or on the dispute between India and Pakistan over the future of Kashmir.

Times staff writer Doyle McManus contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.