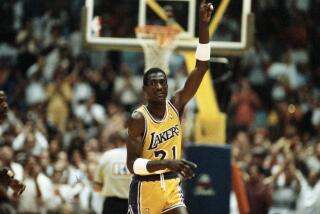

He Played Defensively : Despite His Success in 12 Years With Lakers, Michael Cooper Never Quite Believed He Was Good Enough for Them

- Share via

Michael Cooper was finally right--12 years later.

Since the day he was drafted by the Lakers in the third round out of the University of New Mexico, Cooper waited for the word that he was no longer a Laker.

It finally came last week when he was put on waivers, at his own request, so he could play in Italy.

Despite his jumping ability, his defensive skills and his eventual mastery of the outside shot, Cooper never quite believed he was good enough to be on a team with Magic Johnson or Kareem Abdul-Jabbar. All that talent and not a drop of confidence.

Cooper’s insecurity was never more than a missed jump shot below the surface.

On a swing through the Midwest during a cold, miserable winter in the early 1980s, he suffered a badly sprained ankle. A few nights later in Detroit, Coach Pat Riley pulled Cooper aside before the game and told him to go home and rest in the sun. Since he wasn’t playing anyway, Riley said, why not relax in some warm weather and be ready by the time the Lakers returned.

At halftime, Cooper, dressed in street clothes, sat down next to a reporter at the press table.

“This is it,” said Cooper, anger and frustration in his voice.

“This is what?” the reporter asked.

“This could be the end,” Cooper replied. “Why do you think the Lakers are sending me back? If I go home, I just might wind up off the team. They might use this opportunity to cut me.”

He was serious.

“What are you talking about, Coop? You are one of the most valuable guys on this team,” the reporter said.

“Do you really think the Lakers are just sending me home to rest the ankle?” Cooper said. “I’m not falling for that. They’ll probably put me on waivers. If you leave, you may not come back. They don’t have time to wait on stragglers.”

After the game, the reporter saw Cooper in the locker room.

“Are you still worried?” the reporter asked.

“Nah,” Cooper said, “I’m just . . . what’s that word you used, Jack?”

Trainer Jack Curran, at work nearby, smiled and said: “Paranoid.”

Cooper also smiled. “Yeah,” he said, “I’m paranoid.”

If so, it was a paranoia nurtured by bad fortune.

When he was 2, one of Cooper’s knees was slashed by a coffee can. A hundred stitches later, doctors wondered if he would ever walk again. He wore a metal brace for eight years.

“I couldn’t run, jump or ride skateboards,” he said. “I couldn’t do things other kids could do. I was starving for something.”

Cooper eventually found his meal ticket on a basketball court. He went on to play at Pasadena High, Pasadena City College and New Mexico.

But his confidence level never grew as he did. During a basketball camp several weeks ago at his high school, Cooper was

asked if he had been the star of his prep team.

No, he said, listing three players he thought were better.

NBA teams figured there were at least 59 better players, Cooper lasting well into the third round of the 1978 draft before being taken by the Lakers. Then, before he could sign a contract, he suffered torn knee ligaments and found his pro career in danger of ending before it began.

Owner Jack Kent Cooke signed Cooper anyway, although he wound up playing only seven minutes in his first season.

If looked as if he might not even play that much his second season. The final cut came down to Cooper and Ron Carter. Paul Westhead, then assistant to head coach Jack McKinney, gave his opinion: Go with Carter.

McKinney, in perhaps the key decision of his brief tenure with the Lakers, didn’t listen.

Having spent so much time early in his career living on the edge, Cooper never left it, mentally.

Even his trademark high socks are a means of hiding an insecurity--legs he thinks are too skinny.

“He’s fine,” his wife, Wanda, once said of her husband’s frame of mind, “until he thinks of something else to worry about. . . . Sometimes, he’ll shut a guy down totally on defense, but he’ll come home and say, ‘Damn, I scored only four points.’ Sometimes, I feel like slapping him. Even after a superb game, he’ll come home and get upset about a pass he could have made or should have made.”

Early in his career, Cooper played one of his first strong defensive efforts against the Boston Celtics’ Larry Bird.

In the locker room, Cooper asked a reporter, “Are you going to talk to Bird?

The reporter nodded.

“Ask him what he thought of me and come back and tell me, will you?”

When Bird was effusive in his praise of Cooper, the reporter relayed the Celtic forward’s words.

“He said that? About me ? Really?” Cooper said.

Cooper needed even more of a boost on offense. Year after year, he would talk about how he had practiced shooting all summer. Year after year, he talked about how Riley had encouraged him to shoot more and how he intended to do so. And year after year, he would give up one shot after another, passing instead.

“He always had the feeling,” Riley said, “if he missed two or three shots, I would take him out.”

Yet before he was finished, Cooper wound up making more three-point shots in the playoffs than any player in league history.

His six three-pointers in Game 2 of the 1987 NBA finals against Boston set a league record later tied by the Detroit Pistons’ Bill Laimbeer.

Still, for years, after having a bad game, Cooper would come home and watch footage of himself in the New Mexico days, back when he was “good.”

“He gets a real boost from that,” Wanda said, “watching himself play well.”

Cooper reveled in his role as a sixth man with the Lakers, but if he ever moved down a notch, whatever the reason, he started worrying.

Back when Bob McAdoo was on the team, Riley once inserted both McAdoo and James Worthy, then a rookie, into a game ahead of Cooper. Seated on the bench, Cooper hung his head and draped a towel over it.

“I knew I had to get him in fast,” Riley said, “or I would lose him.”

As Laker after Laker joined the team, from Mike McGee to Byron Scott, Cooper watched and worried. Would they move ahead of him?

“Soon, he was thinking they would be bringing in Jack Curran ahead of him,” Wanda said. “It was something he had to overcome.”

Cooper was just as sensitive about how the media treated him.

He once approached a reporter on the road about a story that appeared the same day in L.A.

“Good story,” Cooper said.

“Oh, you saw it?” the reporter asked.

“Nope.”

How, the reporter wanted to know, could Cooper say it was a good story if he hadn’t even seen it?

“Because Wanda called and told me.”

The reporter started to walk away, but Cooper stopped him.

“Do you have a copy of it with you?” Cooper asked.

“I have one back at the hotel,” the reporter replied. “Do you want to see it?”

Cooper paused, then shook his head.

“It’ll just make me mad,” he said.

On another occasion, Rich Levin of the Herald Examiner quoted Cooper, using material the Laker swingman thought had been off the record.

Furious, Cooper called the paper the next morning and threatened to sue.

As the day wore on, he became increasingly angry. Before that evening’s game, he told a reporter he was going to slap Levin when he saw him.

Finally, after the game, they came face-to-face in the locker room.

“I’ll tell you what I’m going to do,” Cooper said to Levin. “I’m going to put you on probation . . . three games’ probation. If I like what you write, I’ll go back to talking to you. If not, I’ll never speak to you again.”

Levin “passed” his probation.

Among reporters, Cooper was known for his off-the-wall reactions. So much so, that when Levin once found a loose screw in a corner of the locker room, he handed it to Cooper, suggesting it might have fallen out of his head.

“Yeah,” Cooper told him, “but you’d better hang onto it because I’m going to get a lot crazier.”

But there was also a serious side to Cooper, one few saw. He was given the NBA’s J. Walter Kennedy Citizenship Award in 1986. He instituted a Call Coop hotline for troubled teens. He has worked for the homeless. He has provided Laker tickets to exceptional students. And he has spent time with inmates at a juvenile detention center.

Now, after surviving and excelling for a dozen years on one of the great NBA teams, Michael Cooper, 34, is gone from the Lakers.

As he had always predicted.

More to Read

All things Lakers, all the time.

Get all the Lakers news you need in Dan Woike's weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.