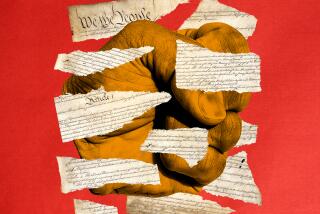

Heading Fast in a Stalin-esque Direction? : Foreign minister raises the red flag of dictatorship

- Share via

Eduard A. Shevardnadze hears the relentlessly tramping feet of approaching dictatorship, and he is disheartened and afraid. And so the man who has been the Soviet Union’s respected foreign minister for five years has done what honorable public servants the world over are often driven to do when the imperatives of personal conscience override the claims of political loyalty. His dramatic and unexpected resignation, announced in Moscow to a stunned meeting of the Congress of People’s Deputies, has called attention as no other gesture could to the ominous and accelerating shift to the right in Soviet political affairs.

Whether Shevardnadze’s decision will arrest that shift is highly doubtful. President Mikhail S. Gorbachev, who appeared to have been as surprised as anyone else by his foreign minister’s resignation, and certainly more angry, seems sure to be given the even greater executive powers that he says he must have to control the chaos spreading across his country. The entrenched and even reactionary forces whom Shevardnadze most directly accused of supporting the movement toward dictatorship are unlikely to be chastened or deterred by his act of self-sacrifice. Maybe the reformers who Shevardnadze says have taken to hiding in the bushes will be inspired and lured back by his somber warning. Maybe. But it’s more than possible that the momentum has already passed, not necessarily to those who are automatic ideological opponents of political and economic aid. It may have passed to those who are now more alarmed about the breakdown in order and control that has been a concomitant of reforms than they are about the possible reimposition of an authoritarian hand.

Secretary of State James A. Baker III, who has developed a productive working relationship with Shevardnadze, is one of those who believe that concerns about a revival of dictatorship in the Soviet Union have to be taken seriously. The political precursors are there for all to see.

Republic after republic has moved to declare its independence or autonomy, mocking Moscow’s efforts to maintain central control and threatening the dissolution of the empire that Lenin and Stalin acquired and held together by force. Production and services around the country, never robust, are collapsing, intensifying shortages and provoking rising public anger and cynicism. The military, its role and standing vastly reduced by Gorbachev’s revolutionary reversal of foreign and defense policies, finds itself wracked by internal ethnic conflicts and weakened by desertions and sinking morale. This is not just a classic formula for the emergence of strong-man rule. In a land that historically lacks all but the most rudimentary familiarity with liberal governance, it is a virtual invitation to dictatorship.

Shevardnadze made it clear that he wasn’t accusing Gorbachev himself of aspiring to be dictator. But Gorbachev’s own recent moves to the right and tough talk about the need for a crackdown clearly seem to leave him a candidate for that role.

An immediate and urgent question is whether Gorbachev’s perceived need to be more attentive to right-wing concerns will be reflected in a tougher international line. It’s known that elements in the military, the KGB and the Communist Party are deeply frustrated over the Soviet Union’s shrinking world role and embrace of dramatic reductions in arms. Shevardnadze, who says his decision to quit is irreversible, has agreed to stay on the job until a replacement can be found, raising at least the hope that his beneficial influence might remain for a while. But whether he lingers for a time or departs quickly, the message Shevardnadze has just delivered remains cause for deep concern. Autocracy is the customary mode of governance in his country, and it may be about to make a foreboding reappearance.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.