The Splendid Tapestry of Arab Life : A HISTORY OF THE ARAB PEOPLES, <i> By Albert Hourani (Harvard University Press: $24.95; 532 pp.)</i>

- Share via

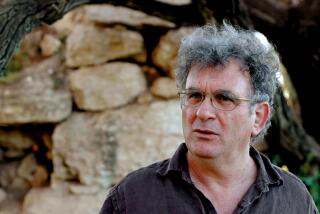

There is something deeply reassuring and even redemptive about this very fine book, which appears just when the United States is attempting in effect to destroy Iraq as a modern Arab nation. Its author, Albert Hourani, is now 75, retired and living in London after a lifetime teaching at Oxford.

Born in Manchester and educated as an Englishman, he is the son of prosperous Lebanese Protestant parents who came to England early in the century, but never lost contact with the Middle East, its peoples and cultures. It would not be inaccurate to say that Hourani is today’s leading historian of the modern Middle East, a scholar whose earlier books on Syria and Lebanon and on “Arabic Thought in the Liberal Age” (an intellectual history of great insight and craftsmanship) are classics, mined by both scholars and general readers for their scope and their fastidiously refined attention to the fabric of Arab life. In a generously conceived set of essays published over the past several decades, Hourani’s sympathy and keen historical sense also have presented to Western and Arab readers a complex structure of innumerable connections: between Arabs and Europeans, Arabs and other Arabs, rulers and ruled, thinkers and their societies.

Now, in what is undoubtedly a masterly summation, the whole story of the Arab peoples is laid out before us by Hourani. There are no other books like it, except--interestingly enough--the similarly grand studies done a generation ago by another Lebanese-Western scholar, Philip Hitti.

Hourani has the advantage over Hitti both in greater amounts of contemporary scholarship to make use of and in relatively up-to-date methods. Hourani’s guiding ideas, however, are resoundingly classical, drawn from the life and works of Ibn Khaldun, the extraordinary 14th-Century Arab historian and philosopher. Put simply, Ibn Khaldun’s argument in the “Muqaddimah” is that there are variety and unity, stability and fluctuation, shifts in power and permanent realities that have organized the Arab world for about a millennium-and-a-half. These are specific to the cohesion of Arab society, whose inner laws Hourani summarizes in a fine passage near the opening:

“A world where a family from southern Arabia could move to Spain, and after six centuries return nearer to its place of origin and still find itself in familiar surroundings, had a unity which transcended divisions of time and space; the Arabic language could open the door to office and influence throughout that world; a body of knowledge, transmitted over the centuries by a known chain of teachers, preserved a moral community even when rulers changed; places of pilgrimage, Mecca and Jerusalem, were unchanging poles of the human world even if power shifted from one city to another; and belief in a God who created and sustained the world could give meaning to the blows of fate.”

The story of the Arab peoples therefore begins with late antiquity as an Arab ethos slowly emerges, based upon the developing splendors of a rich language, a generally pastoral life interspersed with trade and travel, the inherited tradition of Rome, Greece, Judaism and early Christianity. Hourani’s naturally synthesizing style next shows how Islam, as energized and articulated in 7th-Century Arabia by the Prophet Muhammad, flung forth an astonishing new civilization; in a matter of decades, it extended all the way to Morocco and Spain.

In describing the diverse peoples, dynasties and styles included in this vast enterprise, Hourani achieves a level of unruffled generalization that is never reductive; conversely, however, he is rarely dramatic or passionate, leaving the reader often wishing for a glimpsed personality, a vignette, a narrative that might somehow deliver the urgency of lived life and compelling advocacy. This lack is especially felt during Hourani’s description of Abbasid civilization (749-1258), whose seat in Baghdad brought forth one of the greatest flowerings in the Arab enterprise. Given the present American assault on Baghdad, and the fact that the city last was destroyed by Mongols in 1258, one’s sense of outraged grief is only partly attenuated by Hourani’s quiet pages.

For he is at his best when he considers not the dramatic bursts but the abiding features and long trends of Arab life and thought as carried forward by the maintainers and sustainers of human community, and not principally by its challengers or rebels. Surely there are no finer pages than his on Sufis such as Ibn Arabi or metaphysicians such as al-Ghazali.

No one better than Hourani respects the diversity of Arab societies. The status of Jews and Christians, the role of women and, above all, the subtle interplay between Islamic doctrine, practice and social actuality from Andalusia to Syria and Arabia are sifted through with precision and at times elegance. What emerges from the first half of his history is a surprisingly tolerant, even relaxed Arab Weltanschauung dominated not by frothing zealots but by courteous and sensitive sages, urbane magistrates, skilled courtiers.

Yet Hourani’s is a worldly and, for the most part, a secular history. Ever on the alert for and sensitive to the modulations of fortune, he plots the geography of power with great perspicacity. One feature that characterizes rulers from the 8th-Century Umayyads to the Ottomans, for instance, is the physical removal of the sovereign from his principal city to an outlying palace. Another noted by Hourani is the counterpoint between North Africa on the one hand, and on the other the central Islamic lands (Syria, Iraq, Egypt and Arabia), with their sometimes tense, sometimes cordial relationships with Islamic but non-Arab nations such as Iran, Turkey and India. And gradually in the second half of his history, Hourani shows how Europe’s ascendancy came to overshadow the Arabs’ former greatness.

Not that Islam is shown to be the problem: on the contrary. Hourani’s pages on the integration of Islamic faith with Arab culture are a masterpiece of cogent and nuanced exposition, largely because here and elsewhere in the book he never mistakes what a text says for reality. Neither does Hourani tolerate the sloppy propaganda that tries to collapse all aspects of Arab life into a so-called Islamic framework.

There are always conflicts in interpretation--as among Hanbali, Shafii, Maliki, and Hanbali schools--controversies in ijtihad (independent judgment concerning matters of faith); in the role of ulama, caliphs, imams, and gadis, those learned authorities in shariah law; sunnah (orthodoxy) and shiism , and even on matters of vision. Hourani forever explodes the stupid caricature of Islam as a monolithic and unaging block, giving us instead an enormously varied tapestry of religious as well as socio-political configurations, changing, recasting, revising themselves as circumstances around them also change.

Yet while life went on, and the West penetrated more and more of the Arab universe, the world balance of power shifted more and more undeniably to Eastern and Southern disadvantage. The Arabs’ economy seems to have played the central role in the transformation that Hourani notes, especially that economy’s inability to keep us with the West’s greater entrepreneurial and military skill. This in turn gave rise to various waves of reform, nationalism and reaction, from Muhammad Abdul and Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, to Gamal Abdel Nasser and the struggle over Palestine, and most recently to the appearance of several brands of Islamic revivalism.

What Hourani does with particular effectiveness, is, I think, to tell the story in most of its aspects without alarmism or sensationalism. To an Arab or Western reader there is thus the opportunity to see the almost hopelessly exacerbated circumstances of today in a calmer, more reasonably adumbrated setting, one in which the excitements and passions of the moment give way inevitably to an encouraging pattern of mutuality through which Arabs and Westerners can understand themselves, and each other.

It is difficult to overestimate the signal importance of this book for this time. Here at last is a genuinely readable, genuinely responsive history of the Arabs as, I believe, many of them would want to be known to non-Arabs. Although much in it is perforce either summary or suggestive, that (given Hourani’s bibliography) is at least an incentive to further reading and exploration.

More important, however, is that there isn’t a trace in the book of what has been called Orientalism, that ludicrously inept academic and jargon-ridden school for which such ideological fictions as “Islamic (or Arab) rage” or “the Arab mind” are regular stock in trade. Indeed, Hourani dissolves most of the Orientalist edifice, with its polemical defenses, its bristling hostility toward the Arabs and, when they are deployed by modern Arabs, its grotesque sallies in self-laceration.

Not that he is at all either permissive or triumphant: very far from it. He completely controls the best in modern as well as traditional Western scholarship and often lets the Arabs, their poets, historians, sages and ordinary people speak along with, rather than against, that learning. Historical evidence is for him essentially a witness, rather than a symptom, of Arab life.

My main regret is that Hourani’s bibliography on Palestine is so surprisingly stocked with a preponderance of Israeli and Western sources, some of them admittedly excellent. It is a pity that the quite ample work of Palestinian writers and scholars does not get better exposed or used by him, but with much else going on so well in the book, my complaint is a small one.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.