Iron Lady Gets Hero’s Welcome at Pendleton

- Share via

Never mind that some children and even some Marines didn’t know that Margaret Thatcher had been prime minister of Great Britain for almost 12 years.

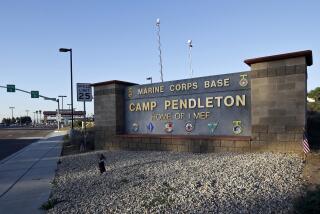

They came to cheer her anyway when she visited Camp Pendleton Thursday to thank Marines and their families for bringing the Persian Gulf War to “such a splendid conclusion.”

“The only way you can retake territory is on land,” Thatcher told a gathering of 1,400 Marines at the base’s School of Infantry. She noted that Gen. Colin Powell, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, recently told her in Washington that Marines had played “a very critical part” in reclaiming Kuwait from the Iraqis.

Earlier in the day, Thatcher experienced gridlock, Southern California-style, as her motorcade was stuck in bumper-to-bumper traffic on Interstate 5 near San Juan Capistrano, where a newspaper delivery truck had rammed into a parked tractor-trailer rig, killing the delivery truck driver.

Inside the base, Thatcher stopped first at the San Onofre School, where she received a yellow Desert Storm ribbon pin.

Eighth-grader Emily Kahler presented Thatcher with a red T-shirt, making her an honorary member of the school’s student council. School officials said that at least 70% of the 875 students--kindergarten through eighth grade--have a parent who served in the Persian Gulf.

“Your Marines and our soldiers worked very closely together in the desert,” Thatcher told about 400 children, ages 10 to 14, in the school’s assembly hall. “We have been friends for a very long time, and we hope that this friendship continues in your generation.”

She also visited the school because she has “an American grandchild who will soon be going to school, so I wanted to see what your education system is like,” said Thatcher, who served as secretary of education before becoming Britain’s first female prime minister.

Thatcher was referring to her 3-year-old grandson, who lives in Dallas with his 37-year-old father, Mark Thatcher, who married an American.

After brief visits to a couple of classrooms, Thatcher stepped into the schoolyard, where some adults and children brushed past State Department and Scotland Yard security officers to get her autograph.

“I put her right next to God,” one man said, after securing Thatcher’s autograph.

Diane Marchese, a kindergarten teacher, said, “It means a lot to these kids for her to come here and say how much she appreciates their daddies for fighting in the war.”

“We’re going to be on TV!” beamed first-grader Michael Duncan as he skipped about excitedly in front of the television cameras. “We’re going to meet Margaret Thatcher.”

The 6-year-old, however, shrugged his shoulders when asked if he knew who she is.

At the School of Infantry, one Marine said Thatcher was “a state senator,” and another said she was an “American congresswoman.”

“She was above us,” said Cpl. Antonio Torres, who sat in a camouflaged light armored vehicle shown to the former head of British government. “She was working for us in Congress.”

Thatcher moved on to the mess hall, where she sat with Gen. Michael Neil for a lunch of chicken noodle soup, twice-baked potato and roasted pork loin.

“It’s the kind of food she likes,” said Sgt. Tony James, who prepared the meal. “I researched it.”

In her address to the Marines, Thatcher attributed the allies’ “splendid victory” in Operation Desert Storm to heavy military spending during the last 10 years.

“No one had better weapons than we had,” she said, “and we owe a great deal to President Reagan for that.”

Thatcher then retired for tea with a group of military wives who lead support groups for military families.

Throughout the three-hour visit to the base, she declined questions from the media. As she left the tea room, a reporter shouted a question, asking for her impressions of the military base.

“Everything is so lovely, and you should be proud of your military and every family,” she said, then walked toward her car.

She stopped to sign an autograph in 23-year-old Tod Isenburg’s diary. “I’m going to save this for my (2-year-old) daughter,” he said. “This is part of history.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.