Library Threatens Legal Action Over ‘Huck’ Manuscript

- Share via

Trustees for the Buffalo, N.Y., public library, who expected two Los Angeles women to donate part of Mark Twain’s original manuscript of “Huckleberry Finn,” are threatening to go to court, charging that the women are demanding money for the priceless document.

The Buffalo library’s board of trustees voted Thursday to establish in court that the library owns the first half of the manuscript, found by one of the sisters two months ago in a trunk containing her grandfather’s belongings. The library already owns the second half, but the first half had been missing for more than 100 years.

“The documentation is clear that this part of the manuscript was given to the library by Mark Twain,” said board chairman Roland R. Benzow, adding that the Buffalo and Erie County Public Library possesses letters specifying Twain’s intent that the manuscript be given to the institution. “At this late stage to have these people deny that gift . . . I think is unfortunate.”

However, a lawyer for the sisters said Friday that they had never promised to give away the manuscript.

Benzow said he was informed Thursday by the library’s attorney that the sisters “wanted megabucks” for the work, though they gave no specific figure. “At that point I told the attorney to go full speed ahead and establish our claim of rights.”

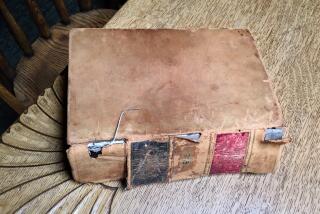

The 665-page manuscript is in the hands of Sotheby’s auction firm, which took possession of the work after its discovery by a granddaughter of James Fraser Gluck, a Buffalo lawyer who corresponded with Twain and was an early collector of the author’s writings.

The papers initially appeared to be headed for auction. But the library’s trustees laid claim to the manuscript, saying that Gluck solicited the document from Twain in 1885 so that it would become part of the library’s collection. The library has possessed the second half of the handwritten manuscript since that time.

However, Twain had evidently misplaced the first half. When he found it, he sent it to Gluck for the library, a claim substantiated in a letter dated 1887 in which Gluck and another library official confirm its receipt. The partial manuscript later vanished.

Shortly after announcement of the historic discovery, Gluck’s granddaughter told The Times that she would probably return the papers to the library.

However, David T. Eames, who represents Gluck’s granddaughters, said he believes that his clients are the lawful owners and never agreed to give the document to the institution.

“It’s within (the sisters) right to sell it or keep it. They own it,” Eames said in a telephone interview from New York. “However they are in favor of uniting both halves of the manuscript and are happy to reach a reasonable resolution with the Buffalo library.”

Eames would not specify if the sisters wanted cash for the manuscript, but said “we’d like to have settlement discussions. The Gluck heirs are prepared to be reasonable but we can’t negotiate in the press.”

Gluck’s granddaughter, who did not want to identified, said Friday that money is not the issue. “The point is we want to be sure who (the manuscript) belongs to and what we should do. . . . We don’t want to be forced to do something before we know it’s right.”

But Benzow said money has become a factor. Though he admitted no official agreement had ever been reached between the library and the sisters over exchange of the manuscript, Benzow said an attorney for Sotheby’s informed him that the sisters were willing to give up the document if they could get a tax deduction for the donation. Later, the sisters apparently changed their minds, wanting to be paid for the manuscript instead.

Eames said the sisters never said they would hand over the manuscript in exchange for a tax break, and said he has a copy of a letter from Sotheby’s attorney to that effect.

Neither an attorney nor a spokesman for Sotheby’s could be reached for comment.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.