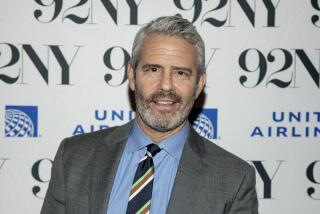

Private Eye Is All Ears : * Trends: How can you tell if your mate is a two-timer? For $2 a minute, Infidelity Hotline operator Bill Colligan will give you the signs.

- Share via

Has your mate been taking longer or more frequent showers lately? Perhaps he or she has adopted a new hairstyle? Dipped into the peroxide bottle for the first time?

And check out that underwear: Did your wife recently decide she just had to have new lingerie? Or has your husband inexplicably traded his boxer shorts for bikini briefs?

If you answer yes to such questions--and others on the 10-point “Suspicion Evaluation Quiz”--private detective Bill Colligan thinks you may have trouble right here in Sin City.

But he doesn’t want you to hire him to investigate. Not any more.

Colligan, who has spent 20 years working on a book called “Adultery Is My Business,” has spent even more time checking up on philandering spouses. Thirty-one years. It’s not a fun job, he says, and frankly, at 53, he admits he is tired of aiming a Telephoto at couples in motel rooms.

Colligan thinks he has a better idea. He wants to stay home, hang out with his telephone and chat about how you can investigate a suspected two-timer.

To do this, Colligan has a new 900 telephone number, the Infidelity Hotline, (900) 990-7977. For $2 a minute, and counting, Colligan says you get:

* Direct contact. Unlike many 900 lines, there is no recorded message. “You don’t have to push any button to answer yes or no to ‘Does he change his underwear three times a day?’ I attempt to evaluate your suspicions. For the most part, the people who call already have strong suspicions and don’t know if they need to hire a private investigator,” Colligan says.

* Help figuring out your goals. For instance, if your suspicions are correct, do you want to save your relationship, perhaps through counseling? Or would you prefer to dump that cheater? Such choices may influence your course of action during your investigation, he says.

* Advice on “the easiest, cheapest way to achieve your goal on your own.” Colligan acknowledges that there’s only so much an amateur can do. Even so, he has dozens of suggestions for those looking for evidence, such as checking a wallet for paper scraps with phone numbers on them.

* Advice on selecting a private detective. Colligan points out that fees and services vary widely. Just picking one from the phone book may not get you what you want.

Although Colligan doesn’t accept cases or provide specific references, he tells callers how to intelligently read phone book advertisements. For example, he notes that California law requires investigators to list their license numbers in ads. Because licenses are issued consecutively, a low number indicates that a detective has been licensed longer, and may be more expensive, than one with a higher number.

* Advice on what to do if your suspicions have been confirmed and you want the relationship to survive. It’s here where Colligan, sounding sometimes like an old-fashioned advice columnist instead of a detective, admits he unabashedly moves into territory usually covered by a marriage counselor

Take the case of a mate who has been cheated on and wants to confront the spouse but save the marriage. Colligan says he tells callers, about 80% of whom are women, not to make accusations.

“I advise them not to say, ‘I have proof,’ even if they do. He’s going to deny it anyway. I tell them, ‘Don’t corner him or make him defend himself. Leave him an exit. . . . My aim is to get them into counseling.”

And when Colligan breaks bad news to a suspecting wife, he often tells her, “I believe the man’s affair has nothing to do with you. He loves you.”

Psychotherapists caution that such advice may be inaccurate, if not hazardous. Says Craig Hands, a Beverly Hills-based clinical psychologist: “It may or may not be true that a man loves his wife. There are numerous reasons why men have affairs. Sometimes, in fact, they do love their wives. Many times they do not. Frequently, they don’t know what love is, period. To make a blanket statement like that is certainly risky.”

Asked if he feels qualified to provide advice, Colligan replies: “Hey, after 30 years, I deal with people every day who have the same problems. If anybody’s an expert on this, I am.” Indeed, Colligan admits knowing the marital minefield personally as well as professionally. He has been married three times (his current marriage has lasted 16 years) and says that he cheated on one of his ex-wives, and one of them cheated on him.

His major problem now is that, rather than giving advice, he spends most days and evenings at his Encino home, waiting for the Infidelity Hotline to ring. Colligan hasn’t done much advertising since opening in early June--just a flyer to 750 homes in the West Los Angeles area. He estimates that it cost about $10,000 to set up the line.

The detective knows he faces an uphill battle doing business through a 900 number, a medium he suspects most people link with pornographic “chat lines.” The 900 phone-line industry, with an estimated $1 billion in sales a year, remains largely unregulated while the Federal Communications Commission, the Federal Trade Commission and Congress decide how to govern it.

And although 900 services now provide information ranging from Catholic News Service movie ratings to ski reports, consumers have few ways of knowing if the number will deliver what it promises.

“There’s no real protection out there yet. I think you have to look at the advertising carefully and look for up-front pricing information at the very least,” says Thomas Blum, manager of new products for Consumers Union, publisher of Consumer Reports magazine. “Our standard advice is that if something sounds too good to be true, it probably is.’ ”

Meanwhile, the Infidelity Hotline pulls in a few calls each day, Colligan says. But when a Times reporter spent three hours with him on a recent evening in hope of hearing what happens on his side of the line, the phone never rang.

“It’s been a slow day. I got one call at 6:30 this morning and one at 1 o’clock in the afternoon,” Colligan reports, adding that the calls last about 28 to 30 minutes each. About 75% of callers decide against investigations.

Chain-smoking behind his desk in tan shorts and black polo shirt, Colligan recalls that his switch to phone work was prompted in part by his wife’s continual criticism that he gave away advice and ought to get paid for it.

Many private investigators do just that, says John T. Lynch, head of John T. Lynch Inc., a Los Angeles investigation firm with offices in New York and Chicago. “We don’t charge for telephone consultation. We have a standard policy of talking to people for up to 15 minutes,” explains Lynch, a lawyer and former FBI agent who says he considered dispensing advice through a 900 line but rejected the idea.

“I didn’t think it was appropriate for a professional man to advertise in that manner,” Lynch says. “But, of course, the world is becoming more liberal continually and we are extremely conservative. It’s an interesting question.”

Colligan’s entry into the 900 business was also motivated by his distaste for delivering bad news. He believes that hearing confirmation of cheating is “probably the most traumatic thing a person has ever heard, unless they’ve been a cancer patient. And if you’re unsuccessful, then you have an unhappy client who may still have the same suspicions and has nothing for his or her money and it wasn’t because I didn’t try.”

By contrast, he claims that working the 900 number is upbeat. “So many people who call a private investigator really don’t need one.” They can figure out the bad news by themselves.

And there’s the added attraction of being “semi-retired.” “As you get older and get a gray beard, people seem to listen more,” he says. “I find it very fulfilling that people are now paying money to hear what I have to say.”