End of Cold War Puts a Calm Face on Superpower Get-Together : Summit: Such sessions are no longer an unpredictable clash of the Soviet and American titans. But they remain a valuable forum.

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Here are the depths to which the long-vaunted superpower summit has fallen:

On Monday night, President Bush will dine with the queen of Thailand, then climb on a plane, fly until dawn and begin a day of talks with the leaders of Spain, Israel, a smattering of foreign ministers and--oh yes, with Soviet President Mikhail S. Gorbachev.

Not long ago, U.S. presidents spoke hopefully of the day when the leaders of the two superpowers might sit down together even once a year. But this week’s Bush-Gorbachev meeting will be the third in four months, and at the White House there is a palpable nostalgia for the bad old days.

“The mood is entirely different,” a senior White House official says of the calm that now attends preparations for such meetings.

Gone are the days of last-minute cramming, exhaustive interagency planning and trying to avoid jet lag. Gone is the gut-wrenching apprehension about what surprises the other side might spring. And gone, some experts say, may be the summit itself--a modern-day anachronism that, increasingly, many believe has no place in the world of the 1990s.

“Summits were meetings between the American President and the Soviet leader to discuss Cold War issues,” argues Michael Mandelbaum, a scholar at the Council on Foreign Relations. “(But) now the Cold War is over, and the Soviet Union no longer exists.”

Indeed, with the Administration still seeking to help Gorbachev maintain control of his unraveling empire, what once was a clash of titans now promises in Madrid to take on the tone of a meeting between supplicant and patron.

“This is for all purposes a man without a country,” an Administration official says of Gorbachev. “The summit at least makes it look like he has a country and is a player.”

But even if the coming Bush-Gorbachev meeting is no longer a dramatic meeting of adversaries, it remains of signal importance. The talks will mark the first face-to-face session between the two leaders since the aborted coup by Soviet hard-liners spurred a dash toward disunion and prompted both sides to call for deep cuts in their nuclear arsenals.

And the fact that the two sides will still be left with large numbers of nuclear weapons means that the two leaders will once again probe the arms-control issues that have been a constant of superpower summits since President John F. Kennedy and Soviet leader Nikita S. Khrushchev met in Vienna more than 30 years ago.

Administration officials say the mini-summit in Madrid will provide a vital forum for each side to gauge the interest of the other in pursuing further, deeper cuts. In addition, Bush is expected to unveil a new, $1.25-billion package of humanitarian aid for the Soviet Union that will give the session a tangible focus.

But while as recently as two years ago, senior U.S. and Soviet officials spent months hammering out in advance the details of the Malta summit, the new era has left neither side feeling any such obligation.

Indeed, when Bush was asked at a news conference Friday whether he plans during the session to answer new Soviet arms-control proposals with specific counteroffers of his own, the President bluntly answered: “No.”

And while the nightmare of Reykjavik--the site of the 1986 meeting in Iceland where Gorbachev took the West by surprise with a proposal to abolish all nuclear weapons--had left U.S. officials wary about further Soviet diplomatic shocks, what was most notable about the last-minute preparations for Madrid was the absence of such concern.

“There used to be the element of surprise,” one Administration official says, but in a crumbling Soviet Union in which Gorbachev has little freedom to maneuver, “that just isn’t a big worry anymore.”

So dramatically have summits been transformed that the talks between Bush and Gorbachev on Tuesday at the opening of the Middle East peace conference will mark the second time in their last three meetings that the discussions have been held as part of a larger gathering.

At the White House, at least, the shift in priorities has been unmistakable. Senior officials have taken pains to play down the significance of the Bush-Gorbachev meeting, and the President himself did his part at his news conference. “The matrix is the Middle East,” he said in fending off questions about the U.S.-Soviet discussions.

Throughout the Cold War, in which summits were few and far between, the idea of making such talks a more regular part of superpower dialogue was a constant theme of U.S. officials and academic experts. Even as recently as the Malta summit less than two years ago, the joint pledge by Bush and Gorbachev to meet at least once a year won bold newspaper headlines and was trumpeted as a major achievement.

But the collapse of the Iron Curtain transformed the adversarial nature of such meetings to the point where last summer Gorbachev could tell Bush during a discussion of their longtime disputes over Afghanistan and Cambodia: “We should have had this conversation a long time ago.”

“That’s when I recognized that things had changed forever,” says a veteran White House official who has attended at least seven summits.

More important, the collapse of the Soviet Union--and the doubts that it has raised about the authority of Gorbachev himself--has made summits both more frequent and less likely to produce a breakthrough.

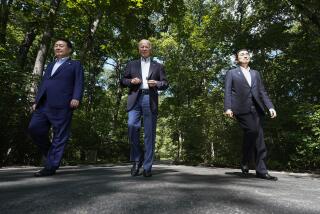

“Basically,” one U.S. official says of Tuesday’s scheduled meeting in Madrid, “this summit isn’t much more than a (photo opportunity) for Gorbachev.”

Academic experts have long warned of the dangers of unrealistic expectations from one-on-one summits, so some saw new merit in a 1990s pattern of get-togethers during the larger multinational gatherings.

“It’s like two lovers who get stale if they spend all their time focusing on each other,” says Kenneth L. Adelman, a senior arms control official during the Ronald Reagan Administration. “There’s a benefit to common pursuit.”

But the experts and Bush Administration officials alike say that the common determination of both governments to orchestrate events designed to shore up the Soviet leader’s prestige may not be healthy if it leads to summits in which Gorbachev’s new, lowered standing leaves him with little room to maneuver.

“The problem for Gorbachev is that he doesn’t have a country,” one Administration official says. “And the problem for us is that we want him to have a country. That means all the eggs are in our basket to try to prop him up.”

Indeed, some experts suggested that the transformation of summits has now also forced a revision in the tenet that often has been cited as the principal obstacle to U.S.-Soviet progress.

Soviet negotiators, citing the refusal of the U.S. Senate to ratify the 1979 SALT II treaty, have long complained that the unpredictability of the American political system has made it unwise to make agreements with the United States.

But Adelman and other experts suggest that the new obligation for Gorbachev to consult with leaders of the 12 Soviet republics before taking any decision--and even then to speak with less than full authority--ought now to encourage an American wariness as well.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.